Islam stabilizes – Key stats on Muslims in the Netherlands 2021

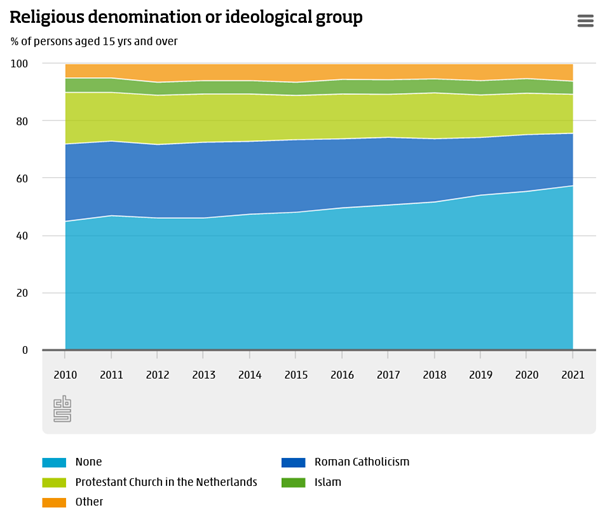

According to a recent publication of Statistics Netherlands, the number of Muslims in the Netherlands stabilizes. The publication, part of a research on social cohesion and well-being, shows the continuing decline of people who identify as religious. In 2021, 58 percent of the Dutch population aged 15 years and over stated they did not belong to a religious denomination or ideological group; this was 45 percent in 2010. The decline continues to be the most significant among Catholics and remains limited but significant among Protestant churches and groups.

The percentage of Muslims in 2021 is 4.6% the same as in 2015 (but between 2015 and 2021 it was close to 5%). This comes down to 745.000 to Age matters as is shown below whereby there are more people who identify as Muslim than as Catholic in in the age range of 18-24.

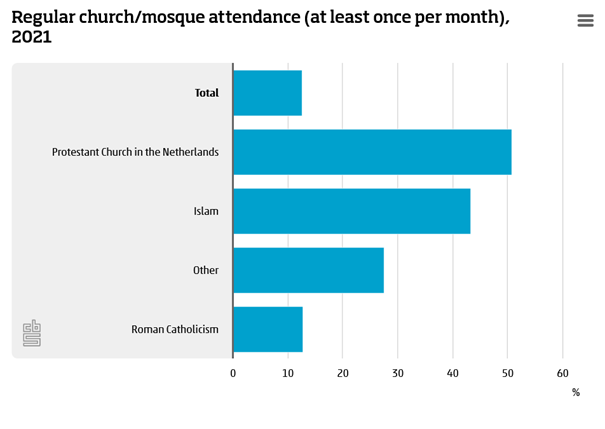

Statistics Netherlands also looks as attendance at religious services. Here, 43% of the Muslims visit a mosque at least once a month.

The percentages over the years vary a little here.

| 1998/1999 –> | 47% |

| 2004 – 2008 –> | 35% |

| 2014 –> | 39% |

| 2021–> | 43% |

Do they fall within the error margins of the research, do they point to a changing role of the mosques, or fluctuations in religiosity? It is unclear.

What does this mean?

It is rather difficult to interpret these overall findings as well. Do they indeed indicate a decrease in religious identification, religiosity, religiousness? To a further decline in institutional religion perhaps?

It would be interesting to follow up on this and for example look at how people who identify themselves as belonging to a specific religion (or those who do not really, or not fully, or do not know), how they experience religiosity, institutions and so on in these changing circumstances. Is there a growing tendency to view oneself as a minority (since the nones are the majority according to Statistics Netherlands) and how does this differ per religion? Do these changes mean that we as researcher have to adjust our methodologies and definitions and how we approach the field (and what is the field actually)?

Furthermore, although church visit and identification with Christianity may be declining, there is also a tendency among populist and mainstream political parties to identify the Netherlands as a Christian, secular-Christian, Judeo-Christian country or a country based upon such heritage. We may then ask how does the decline of self-identification and commitment to Christianity and the surge in identifying the nation as (based upon) Christianity affect the space afforded to racialized minorities such as Jews, Muslims and Hindus to create and express a sense of belonging and of difference?