| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Sep | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

Pages

- About

- C L O S E R moves to….C L O S E R

- Contact Me

- Interventions – Forces that Bind or Divide

- ISIM Review via Closer

- Publications

- Research

Categories

- (Upcoming) Events (33)

- [Online] Publications (26)

- Activism (117)

- anthropology (113)

- Method (13)

- Arts & culture (88)

- Asides (2)

- Blind Horses (33)

- Blogosphere (192)

- Burgerschapserie 2010 (50)

- Citizenship Carnival (5)

- Dudok (1)

- Featured (5)

- Gender, Kinship & Marriage Issues (265)

- Gouda Issues (91)

- Guest authors (58)

- Headline (76)

- Important Publications (159)

- Internal Debates (275)

- International Terrorism (437)

- ISIM Leiden (5)

- ISIM Research II (4)

- ISIM/RU Research (171)

- Islam in European History (2)

- Islam in the Netherlands (219)

- Islamnews (56)

- islamophobia (59)

- Joy Category (56)

- Marriage (1)

- Misc. News (891)

- Morocco (70)

- Multiculti Issues (749)

- Murder on theo Van Gogh and related issues (326)

- My Research (118)

- Notes from the Field (82)

- Panoptic Surveillance (4)

- Public Islam (244)

- Religion Other (109)

- Religious and Political Radicalization (635)

- Religious Movements (54)

- Research International (55)

- Research Tools (3)

- Ritual and Religious Experience (58)

- Society & Politics in the Middle East (159)

- Some personal considerations (146)

- Deep in the woods… (18)

- Stadsdebat Rotterdam (3)

- State of Science (5)

- Twitwa (5)

- Uncategorized (74)

- Young Muslims (459)

- Youth culture (as a practice) (157)

General

- ‘In the name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful’

- – Lotfi Haddi –

- …Kelaat Mgouna…….Ait Ouarchdik…

- ::–}{Nour Al-Islam}{–::

- Al-islam.nl De ware godsdienst voor Allah is de Islam

- Allah Is In The House

- Almaas

- amanullah.org

- Amr Khaled Official Website

- An Islam start page and Islamic search engine – Musalman.com

- arabesque.web-log.nl

- As-Siraat.net

- assadaaka.tk

- Assembley for the Protection of Hijab

- Authentieke Kennis

- Azaytouna – Meknes Azaytouna

- berichten over allochtonen in nederland – web-log.nl

- Bladi.net : Le Portail de la diaspora marocaine

- Bnai Avraham

- BrechtjesBlogje

- Classical Values

- De islam

- DimaDima.nl / De ware godsdienst? bij allah is de islam

- emel – the muslim lifestyle magazine

- Ethnically Incorrect

- fernaci

- Free Muslim Coalition Against Terrorism

- Frontaal Naakt. Ongesluierde opinies, interviews & achtergronden

- Hedendaagse wetenswaardigheden…

- History News Network

- Homepage Al Nisa

- hoofddoek.tk – Een hoofddoek, je goed recht?

- IMRA: International Muslima Rights Association

- Informed Comment

- Insight to Religions

- Instapundit.com

- Interesting Times

- Intro van Abdullah Biesheuvel

- islaam

- Islam Ijtihad World Politics Religion Liberal Islam Muslim Quran Islam in America

- Islam Ijtihad World Politics Religion Liberal Islam Muslim Quran Islam in America

- Islam Website: Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic, Religion

- Islamforum

- Islamic Philosophy Online

- Islamica Magazine

- islamicate

- Islamophobia Watch

- Islamsevrouw.web-log.nl

- Islamwereld-alles wat je over de Islam wil weten…

- Jihad: War, Terrorism, and Peace in Islam

- JPilot Chat Room

- Madrid11.net

- Marocstart.nl – De marokkaanse startpagina!

- Maryams.Net – Muslim Women and their Islam

- Michel

- Modern Muslima.com

- Moslimjongeren Amsterdam

- Moslimjongeren.nl

- Muslim Peace Fellowship

- Muslim WakeUp! Sex & The Umma

- Muslimah Connection

- Muslims Against Terrorism (MAT)

- Mutma’inaa

- namira

- Otowi!

- Ramadan.NL

- Religion, World Religions, Comparative Religion – Just the facts on the world\’s religions.

- Ryan

- Sahabah

- Salafi Start Siden – The Salafi Start Page

- seifoullah.tk

- Sheikh Abd al Qadir Jilani Home Page

- Sidi Ahmed Ibn Mustafa Al Alawi Radhiya Allahu T’aala ‘Anhu (Islam, tasawuf – Sufism – Soufisme)

- Stichting Vangnet

- Storiesofmalika.web-log.nl

- Support Sanity – Israel / Palestine

- Tekenen van Allah\’s Bestaan op en in ons Lichaam

- Terrorism Unveiled

- The Coffee House | TPMCafe

- The Inter Faith Network for the UK

- The Ni’ma Foundation

- The Traveller’s Souk

- The \’Hofstad\’ terrorism trial – developments

- Thoughts & Readings

- Uitgeverij Momtazah | Helmond

- Un-veiled.net || Un-veiled Reflections

- Watan.nl

- Welkom bij Islamic webservices

- Welkom bij vangnet. De site voor islamitische jongeren!

- welkom moslim en niet moslims

- Yabiladi Maroc – Portail des Marocains dans le Monde

Dutch [Muslims] Blogs

- Hedendaagse wetenswaardigheden…

- Abdelhakim.nl

- Abdellah.nl

- Abdulwadud.web-log.nl

- Abou Jabir – web-log.nl

- Abu Bakker

- Abu Marwan Media Publikaties

- Acta Academica Tijdschrift voor Islam en Dialoog

- Ahamdoellilah – web-log.nl

- Ahlu Soennah – Abou Yunus

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Al Moudjahideen

- Al-Adzaan

- Al-Islaam: Bismilaahi Rahmaani Rahiem

- Alesha

- Alfeth.com

- Anoniempje.web-log.nl

- Ansaar at-Tawheed

- At-Tibyan Nederland

- beni-said.tk

- Blog van moemina3 – Skyrock.com

- bouchra

- CyberDjihad

- DE SCHRIJVENDE MOSLIMS

- DE VROLIJKE MOSLIM ;)

- Dewereldwachtopmij.web-log.nl

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Eali.web-log.nl

- Een genade voor de werelden

- Enige wapen tegen de Waarheid is de leugen…

- ErTaN

- ewa

- Ezel & Os v2

- Gizoh.tk [.::De Site Voor Jou::.]

- Grappige, wijze verhalen van Nasreddin Hodja. Turkse humor.

- Hanifa Lillah

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Het laatste nieuws lees je als eerst op Maroc-Media

- Homow Universalizzz

- Ibn al-Qayyim

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- Islam Blog – Juli 2007

- Islam in het Nieuws – web-log.nl

- Islam, een religie

- Islam, een religie

- Islamic Sisters – web-log.nl

- Islamiway’s Weblog

- Islamtawheed’s Blog

- Jihaad

- Jihad

- Journalista

- La Hawla Wa La Quwatta Illa Billah

- M O S L I M J O N G E R E N

- M.J.Ede – Moslimjongeren Ede

- Mahdi\’s Weblog | Vrijheid en het vrije woord | punt.nl: Je eigen gratis weblog, gratis fotoalbum, webmail, startpagina enz

- Maktab.nl (Zawaj – islamitische trouwsite)

- Marocdream.nl – Home

- Marokkaanse.web-log.nl

- Marokkanen Weblog

- Master Soul

- Miboon

- Miesjelle.web-log.nl

- Mijn Schatjes

- Moaz

- moeminway – web-log.nl

- Moslima_Y – web-log.nl

- mosta3inabilaah – web-log.nl

- Muhaajir in islamitisch Zuid-Oost Azië

- Mumin al-Bayda (English)

- Mustafa786.web-log.nl

- Oprecht – Poort tot de kennis

- Said.nl

- saifullah.nl – Jihad al-Haq begint hier!

- Salaam Aleikum

- Sayfoudien – web-log.nl

- soebhanAllah

- Soerah19.web-log.nl – web-log.nl

- Steun Palestina

- Stichting Moslimanetwerk

- Stories of Malika

- supermaroc

- Ummah Nieuws – web-log.nl

- Volkskrant Weblog — Alib Bondon

- Volkskrant Weblog — Moslima Journalista

- Vraag en antwoord…

- wat is Islam

- Wat is islam?

- Weblog – a la Maroc style

- website van Jamal

- Wij Blijven Hier

- Wij Blijven Hier

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- www.moslima.web-log.nl

- Yakini Time

- Youth Of Islam

- Youth Of Islam

- [fikra]

Non-Dutch Muslims Blogs

- Lanallah __Islamic BlogZine__

- This journey ends but only with The Beginning

- ‘the middle place’

- …Never Judge a Person By His or Her Blog…

- …under the tree…

- A Comment on PMUNA

- A Dervish’s Du`a’

- A Family in Baghdad

- A Garden of Children

- A Muslim Mother’s Thoughts / Islamic Parenting

- A Struggle in Uncertainty, Such is Life

- About Afghanistan

- adnan.org: good design, bad idea

- Afiyah

- Ahmeds World of Islam

- Al Musawwir

- Al-Musharaka

- Almiraya tBLOG – O, happy the soul that saw its own faults

- Almusawwir

- an open window

- Anak Alam

- aNaRcHo AkBaR

- Anthology

- AnthroGal’s World

- Arabian Passion

- ArRihla

- Articles Blog

- Asylum Seeker

- avari-nameh

- Baghdad Burning

- Being Noor Javed

- Bismillah

- bloggin’ muslimz.. Linking Muslim bloggers around the globe

- Blogging Islamic Perspective

- Chapati Mystery

- City of Brass – Principled pragmatism at the maghrib of one age, the fajr of another

- COUNTERCOLUMN: All Your Bias Are Belong to Us

- d i z z y l i m i t s . c o m >> muslim sisters united w e b r i n g

- Dar-al-Masnavi

- Day in the life of an American Muslim Woman

- Don’t Shoot!…

- eat-halal guy

- Eye on Gay Muslims

- Eye on Gay Muslims

- Figuring it all out for nearly one quarter of a century

- Free Alaa!

- Friends, Romans, Countrymen…. lend me 5 bux!

- From Peer to Peer ~ A Weblog about P2P File & Idea Sharing and More…

- Ghost of a flea

- Ginny’s Thoughts and Things

- God, Faith, and a Pen: The Official Blog of Dr. Hesham A. Hassaballa

- Golublog

- Green Data

- gulfreporter

- Hadeeth Blog

- Hadouta

- Hello from the land of the Pharaoh

- Hello From the land of the Pharaohs Egypt

- Hijabi Madness

- Hijabified

- HijabMan’s Blog

- Ihsan-net

- Inactivity

- Indigo Jo Blogs

- Iraq Blog Count

- Islam 4 Real

- Islamiblog

- Islamicly Locked

- Izzy Mo’s Blog

- Izzy Mo’s Blog

- Jaded Soul…….Unplugged…..

- Jeneva un-Kay-jed- My Bad Behavior Sanctuary

- K-A-L-E-I-D-O-S-C-O-P-E

- Lawrence of Cyberia

- Letter From Bahrain

- Life of an American Muslim SAHM whose dh is working in Iraq

- Manal and Alaa\’s bit bucket | free speech from the bletches

- Me Vs. MysElF

- Mental Mayhem

- Mere Islam

- Mind, Body, Soul : Blog

- Mohammad Ali Abtahi Webnevesht

- MoorishGirl

- Muslim Apple

- muslim blogs

- Muslims Under Progress…

- My heart speaks

- My Little Bubble

- My Thoughts

- Myself | Hossein Derakhshan’s weblog (English)

- neurotic Iraqi wife

- NINHAJABA

- Niqaabi Forever, Insha-Allah Blog with Islamic nasheeds and lectures from traditional Islamic scholars

- Niqabified: Irrelevant

- O Muhammad!

- Otowi!

- Pak Positive – Pakistani News for the Rest of Us

- Periphery

- Pictures in Baghdad

- PM’s World

- Positive Muslim News

- Procrastination

- Prophet Muhammad

- Queer Jihad

- Radical Muslim

- Raed in the Middle

- RAMBLING MONOLOGUES

- Rendering Islam

- Renegade Masjid

- Rooznegar, Sina Motallebi’s WebGard

- Sabbah’s Blog

- Salam Pax – The Baghdad Blog

- Saracen.nu

- Scarlet Thisbe

- Searching for Truth in a World of Mirrors

- Seeing the Dawn

- Seeker’s Digest

- Seekersdigest.org

- shut up you fat whiner!

- Simply Islam

- Sister Scorpion

- Sister Soljah

- Sister Surviving

- Slow Motion in Style

- Sunni Sister: Blahg Blahg Blahg

- Suzzy’s id is breaking loose…

- tell me a secret

- The Arab Street Files

- The Beirut Spring

- The Islamic Feminista

- The Land of Sad Oranges

- The Muslim Contrarian

- The Muslim Postcolonial

- The Progressive Muslims Union North America Debate

- The Rosetta Stone

- The Traceless Warrior

- The Wayfarer

- TheDesertTimes

- think halal: the muslim group weblog

- Thoughts & Readings

- Through Muslim Eyes

- Turkish Torque

- Uncertainty:Iman and Farid’s Iranian weblog

- UNMEDIA: principled pragmatism

- UNN – Usayd Network News

- Uzer.Aurjee?

- Various blogs by Muslims in the West. – Google Co-op

- washed away memories…

- Welcome to MythandCulture.com and to daily Arrows – Mythologist, Maggie Macary’s blog

- word gets around

- Writeous Sister

- Writersblot Home Page

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- www.Mas’ud’s blog

- \’Aqoul

- ~*choco-bean*~

General Islam Sites

- :: Islam Channel :: – Welcome to IslamChannel Official Website

- Ad3iyah(smeekbeden)

- Al-maktoum Islamic Centre Rotterdam

- Assalamoe Aleikoem Warhmatoe Allahi Wa Barakatuhoe.

- BouG.tk

- Dades Islam en Youngsterdam

- Haq Islam – One stop portal for Islam on the web!

- Hight School Teacher Muhammad al-Harbi\’s Case

- Ibn Taymiyah Pages

- Iskandri

- Islam

- Islam Always Tomorrow Yesterday Today

- Islam denounces terrorism.com

- Islam Home

- islam-internet.nl

- Islamic Artists Society

- Leicester~Muslims

- Mere Islam

- MuslimSpace.com | MuslimSpace.com, The Premiere Muslim Portal

- Safra Project

- Saleel.com

- Sparkly Water

- Statements Against Terror

- Understand Islam

- Welcome to Imaan UK website

Islamic Scholars

Social Sciences Scholars

- ‘ilm al-insaan: Talking About the Talk

- :: .. :: zerzaust :: .. ::

- After Sept. 11: Perspectives from the Social Sciences

- Andrea Ben Lassoued

- Anth 310 – Islam in the Modern World (Spring 2002)

- anthro:politico

- AnthroBase – Social and Cultural Anthropology – A searchable database of anthropological texts

- AnthroBlogs

- AnthroBoundaries

- Anthropologist Community

- anthropology blogs

- antropologi.info – Social and Cultural Anthropology in the News

- Arabist Jansen

- Between Secularization and Religionization Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

- Bin Gregory Productions

- Blog van het Blaise Pascal Instituut

- Boas Blog

- Causes of Conflict – Thoughts on Religion, Identity and the Middle East (David Hume)

- Cicilie among the Parisians

- Cognitive Anthropology

- Comunidade Imaginada

- Cosmic Variance

- Critical Muslims

- danah boyd

- Deep Thought

- Dienekes’ Anthropology Blog

- Digital Islam

- Erkan\’s field diary

- Ethno::log

- Evamaria\’s ramblings –

- Evan F. Kohlmann – International Terrorism Consultant

- Experimental Philosophy

- For the record

- Forum Fridinum [Religionresearch.org]

- Fragments weblog

- From an Anthropological Perspective

- Gregory Bateson

- Islam & Muslims in Europe *)

- Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic, Religion

- Islam, Muslims, and an Anthropologist

- Jeremy’s Weblog

- JourneyWoman

- Juan Cole – ‘Documents on Terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’

- Keywords

- Kijken naar de pers

- languagehat.com

- Left2Right

- Leiter Reports

- Levinas and multicultural society

- Links on Islam and Muslims

- log.squig.org

- Making Anthropology Public

- Martijn de Koning Research Pages / Onderzoekspaginas

- Material World

- MensenStreken

- Modern Mass Media, Religion and the Imagination of Communities

- Moroccan Politics and Perspectives

- Multicultural Netherlands

- My blog’s in Cambridge, but my heart is in Accra

- National Study of Youth and Religion

- Natures/Cultures

- Nomadic Thoughts

- On the Human

- Philip Greenspun’s Weblog:

- Photoethnography.com home page – a resource for photoethnographers

- Qahwa Sada

- RACIAL REALITY BLOG

- Religion Gateway – Academic Info

- Religion News Blog

- Religion Newswriters Association

- Religion Research

- rikcoolsaet.be – Rik Coolsaet – Homepage

- Rites [Religionresearch.org]

- Savage Minds: Notes and Queries in Anthropology – A Group Blog

- Somatosphere

- Space and Culture

- Strange Doctrines

- TayoBlog

- Teaching Anthropology

- The Angry Anthropologist

- The Gadflyer

- The Immanent Frame | Secularism, religion and the public sphere

- The Onion

- The Panda\’s Thumb

- TheAnthroGeek

- This Blog Sits at the

- This Blog Sits at the intersection of Anthropology & Economics

- verbal privilege

- Virtually Islamic: Research and News about Islam in the Digital Age

- Wanna be an Anthropologist

- Welcome to Framing Muslims – International Research Network

- Yahya Birt

Women's Blogs / Sites

- * DURRA * Danielle Durst Britt

- -Fear Allah as He should be Feared-

- a literary silhouette

- a literary silhouette

- A Thought in the Kingdom of Lunacy

- AlMaas – Diamant

- altmuslimah.com – exploring both sides of the gender divide

- Assalaam oe allaikoum Nour al Islam

- Atralnada (Morning Dew)

- ayla\’s perspective shifts

- Beautiful Amygdala

- bouchra

- Boulevard of Broken Dreams

- Chadia17

- Claiming Equal Citizenship

- Dervish

- Fantasy web-log – web-log.nl

- Farah\’s Sowaleef

- Green Tea

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Hilsen Fra …

- Islamucation

- kaleidomuslima: fragments of my life

- Laila Lalami

- Marhaban.web-log.nl – web-log.nl

- Moslima_Y – web-log.nl

- Muslim-Refusenik The official website of Irshad Manji

- Myrtus

- Noor al-Islaam – web-log.nl

- Oh You Who Believe…

- Raising Yousuf: a diary of a mother under occupation

- SAFspace

- Salika Sufisticate

- Saloua.nl

- Saudi Eve

- SOUL, HEART, MIND, AND BODY…

- Spirit21 – Shelina Zahra Janmohamed

- Sweep the Sunshine | the mundane is the edge of glory

- Taslima Nasrin

- The Color of Rain

- The Muslimah

- Thoughts Of A Traveller

- Volkskrant Weblog — Islam, een goed geloof

- Weblog Raja Felgata | Koffie Verkeerd – The Battle | punt.nl: Je eigen gratis weblog, gratis fotoalbum, webmail, startpagina enz

- Weblog Raja Felgata | WRF

- Writing is Busy Idleness

- www.moslima.web-log.nl

- Zeitgeistgirl

- Zusters in Islam

- ~:: MARYAM ::~ Tasawwuf Blog

Ritueel en religieuze beleving Nederland

- – Alfeth.com – NL

- :: Al Basair ::

- Abu Marwan Media Publikaties

- Ahlalbait Jongeren

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Al-Amien… De Betrouwbare – Home

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Wasatiyyah.com – Home

- Anwaar al-Islaam

- anwaaralislaam.tk

- Aqiedah’s Weblog

- Arabische Lessen – Home

- Arabische Lessen – Home

- Arrayaan.net

- At-taqwa.nl

- Begrijp Islam

- Bismillaah – deboodschap.com

- Citaten van de Salaf

- Dar al-Tarjama WebSite

- Dawah-online.com

- de koraan

- de koraan

- De Koran . net – Het Islaamitische Fundament op het Net – Home

- De Leidraad, een leidraad voor je leven

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Faadi Community

- Ghimaar

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Ibn al-Qayyim

- IMAM-MALIK-Alles over Islam

- IQRA ROOM – Koran studie groep

- Islaam voor iedereen

- Islaam voor iedereen

- Islaam: Terugkeer naar het Boek (Qor-aan) en de Soennah volgens het begrip van de Vrome Voorgangers… – Home

- Islaam: Terugkeer naar het Boek (Qor-aan) en de Soennah volgens het begrip van de Vrome Voorgangers… – Home

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- islam :: messageboard

- Islam City NL, Islam en meer

- Islam, een religie

- Islamia.nl – Islamic Shop – Islamitische Winkel

- Islamitische kleding

- Islamitische kleding

- Islamitische smeekbedes

- islamtoday

- islamvoorjou – Informatie over Islam, Koran en Soenah

- kebdani.tk

- KoranOnline.NL

- Lees de Koran – Een Openbaring voor de Mensheid

- Lifemakers NL

- Marocstart.nl | Islam & Koran Startpagina

- Miesbahoel Islam Zwolle

- Mocrodream Forums

- Moslims in Almere

- Moslims online jong en vernieuwend

- Nihedmoslima

- Oprecht – Poort tot de kennis

- Quraan.nl :: quran koran kuran koeran quran-voice alquran :: Luister online naar de Quraan

- Quraan.nl online quraan recitaties :: Koran quran islam allah mohammed god al-islam moslim

- Selefie Nederland

- Stichting Al Hoeda Wa Noer

- Stichting Al Islah

- StION Stichting Islamitische Organisatie Nederland – Ahlus Sunnat Wal Djama\’ah

- Sunni Publicaties

- Sunni.nl – Home

- Teksten van Aboe Ismaiel

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Uw Keuze

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.al-thabaat.com

- www.hijaab.com

- www.uwkeuze.net

- Youth Of Islam

- Zegswijzen van de Wijzen

- \’\’ Leid ons op het rechte pad het pad degenen aan wie Gij gunsten hebt geschonken\’\’

Muslim News

Moslims & Maatschappij

Arts & Culture

- : : SamiYusuf.com : : Copyright Awakening 2006 : :

- amir normandi, photographer – bio

- Ani – SINGING FOR THE SOUL OF ISLAM – HOME

- ARTEEAST.ORG

- AZIZ

- Enter into The Home Website Of Mecca2Medina

- Kalima Translation – Reviving Translation in the Arab world

- lemonaa.tk

- MWNF – Museum With No Frontiers – Discover Islamic Art

- Nader Sadek

Misc.

'Fundamentalism'

Islam & commerce

2

Morocco

[Online] Publications

- ACVZ :: | Preliminary Studies | About marriage: choosing a spouse and the issue of forced marriages among Maroccans, Turks and Hindostani in the Netherlands

- ACVZ :: | Voorstudies | Over het huwelijk gesproken: partnerkeuze en gedwongen huwelijken onder Marokkaanse, Turkse en Hindostaanse Nederlanders

- Kennislink – ‘Dit is geen poep wat ik praat’

- Kennislink – Nederlandse moslims

Religious Movements

- :: Al Basair ::

- :: al Haqq :: de waarheid van de Islam ::

- ::Kalamullah.Com::

- Ahloelhadieth.com

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- al-Madinah (Medina) The City of Prophecy ; Islamic University of Madinah (Medina), Life in Madinah (Medina), Saudi Arabia

- American Students in Madinah

- Aqiedah’s Weblog

- Dar al-Tarjama WebSite

- Faith Over Fear – Feiz Muhammad

- Instituut voor Opvoeding & Educatie

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- islamtoday

- Moderate Muslims Refuted

- Rise And Fall Of Salafi Movement in the US by Umar Lee

- Selefie Dawah Nederland

- Selefie Nederland

- Selefienederland

- Stichting Al Hoeda Wa Noer

- Teksten van Aboe Ismaiel

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- Youth Of Islam

“Now, it’s gonna be a long one” – some first conclusions from the Egyptian revolution

Posted on February 8th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: anthropology, Guest authors, Headline, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Guest Author: Samuli Schielke

Sunday, February 6, 2011

Today is my scheduled day of departure from Egypt. As I sit on Cairo airport waiting for my flight to Frankfurt, it is the first time on this trip that regret anything – I regret that I am leaving today and not staying. I have told to every Egyptian I have met today that I am not escaping, just going for my work at the university and returning soon. But perhaps it has been more to convince myself than them. My European friend who like me came here last Monday is staying for another two weeks. My American friend in Imbaba tells that for months, she has been homesick to go to America and see her parents and family again. But now when the US government would even give her a free flight, she says that she cannot go. This is her home, and she is too attached to the people, and especially to her husband. Two days ago, he was arrested on his way back from Tahrir square, held captive for four hours, interrogated, and tortured with electroshocks. He is now more determined than ever. How could she leave him behind? But today is my scheduled departure, and I only intended to come for a week and then return to do what I can to give a balanced idea of the situation in Egypt in the public debates in Germany and Finland. Tomorrow I will give a phone interview to Deutschlandradio (a German news radio), and on Tuesday I will give a talk in Helsinki in Finland. Right now, I feel that maintaining high international pressure on the Egyptian government is going to be crucial, and I will do what I can.

There remains little to be reported about the beginning day in Cairo, but maybe I can try to draw some first conclusion from this week.

The morning in Cairo today was marked by a return to normality everywhere except on Tahrir Square itself, where the demonstrations continue. Now that the streets are full with people again, the fear I felt in the past days on the streets is gone, too. If I stayed, today would be the day when I would again walk through the streets of Cairo, talk with people and feel the atmosphere.

From what I know from this morning’s short excursion in Giza and Dokki, the people remain split, but also ready to change their mind. As my Egyptian friend and I took a taxi to Dokki, the taxi driver was out on the street for the first time since 24 January, and had fully believed what the state television had told him. But as my friend, a journalist, told him what was really going on, the driver amazingly quickly shifted his opinion again, and remembered the old hatred against the oppressive system, the corruption, and the inflation that brought people to the streets last week. A big part of the people here seem impressively willing to change their mind, and if many of those who were out on the streets on 28 January – and also of those who stayed home – have changed their mind in favour of normality in the past days, they do expect things to get better now, and if they don’t, they are likely to change their minds again. This is the impression I also got from the taxi driver who took me to the airport from Dokki. He, too, had not left his house for eleven days, not out of fear for himself, but because he felt that he must stay at home to protect his family. He was very sceptical of what Egyptian television was telling, but he did expect things to get better now. What will he and others like him do if things don’t get better?

As I came to Egypt a week ago I expected that the revolution would follow one of the two courses that were marked by the events of 1989: either a successful transition to democracy by overthrowing of the old regime as happened in eastern Europe, or shooting everybody dead as happened in China. Again, my prediction was wrong (although actually the government did try the Chinese option twice, only unsuccessfully), and now something more complicated is going on.

This is really the question now: Will things get better or not? In other words: Was the revolution a success of a failure? And on what should its success be measured? If it is to be measured on the high spirits and sense of dignity of those who stood firm against the system, it was a success. If it is to be measured by the emotional switch of those who after the Friday of Anger submitted again to the mixture of fear and admiration of the president’s sweet words, it was a failure. If the immense local and international pressure on the Egyptian government will effect sustainable political change, it will be a success. But it will certainly not be an easy success, and very much continuous pressure is needed, as a friend of mine put it in words this morning: “Now, it’s gonna be a long one.”

In Dokki I visited a European-Latin American couple who are determined to stay in Egypt. He was on Tahrir Square on Wednesday night when the thugs attacked the demonstrators, and he spent all night carrying wounded people to the makeshift field hospital. He says: “What really worries me is the possibility that Mubarak goes and is replaced by Omar Suleyman who then sticks to power with American approval. He is the worst of them all.” Just in case, he is trying to get his Latin American girlfriend a visa for Schengen area, because if Omar Suleyman’s campaign against alleged “foreign elements” and “particular agendas” continues, the day may come when they are forced to leave after all.

A few words about the foreigners participating in the revolution need to be said.. Like the Spanish civil war once, so also the Egyptian revolution has moved many foreigners, mostly those living in Egypt since long, to participate in the struggle for democracy. This has been an ambiguous struggle in certain ways, because the state television has exploited the presence of foreigners on Tahrir Square in order to spread quite insane conspiracy theories about foreign agendas behind the democracy movement. The alliance against Egypt, the state television wants to make people believe, is made up of agents of Israel, Hamas, and Iran. That’s about the most insane conspiracy theory I have heard of for a long time. But unfortunately, conspiracy theories do not need to be logical to be convincing. But to step back to the ground of reality, if this revolution has taught me one thing is that the people of Egypt do not need to look up to Europe or America to imagine a better future. They have shown themselves capable of imagining a better future of their own making (with some important help from Tunisia). Compared to our governments with their lip service to democracy and appeasement of dictators, Egyptians have given the world an example in freedom and courage which we all should look up to as an example. This sense of admiration and respect is what has drawn so many foreigners to Tahrir Square in the past days, including myself.

As an anthropologist who has long worked on festive culture, I noticed a strikingly festive aspect to the revolutionary space of Tahrir Square. It is not just a protest against an oppressive regime and a demand for freedom. In itself, it is freedom. It is a real, actual, lived moment of the freedom and dignity that the pro-democracy movement demands. As such, it is an ambiguous moment, because its stark sense of unity (there is a consensus of having absolutely no party slogans on the square) and power is bound to be transient, for even in the most successful scenario it will be followed by a long period of political transition, tactics, negotiations, party politics – all kinds of business that will not be anything like that moment of standing together and finally daring to say “no!”. But thanks to its utopian nature, it is also indestructible. Once it has been realised, it cannot be wiped out of people’s minds again. It will be an experience that, with different colourings and from different perspectives, will mark an entire generation.

In a different sense, however, the relationship of transience and persistence is a critical one. A revolution is not a quick business; it requires persistence. Some have that persistence, and millions have continued demonstrating (remember that in Alexandria and all major provincial cities there are ongoing in demonstrations as well). Others, however, had the anger and energy to go out to the streets on the Friday of Anger on 28 January to say loudly “No!”, but not the persistence to withstand the lure of the president’s speech on Tuesday 1 February when Mubarak showed himself as a mortal human, an old soldier determined to die and be buried in his country. A journalist noted to me that this was the first time Mubarak has ever mentioned his own mortality – the very promise that he will die one day seems to have softened many people.

Speaking of generations, this revolution has been called a youth revolution by all sides, be it by the demonstrators themselves, the state media, or international media. Doing so has different connotations. It can mean highlighting the progressive nature of the movement, but it can also mean depicting the movement as immature. In either case, in my experience the pro-democracy movement is not really a youth movement. People of all ages support the revolution, just like there are people of all ages who oppose it or are of two minds about it. If most of the people out in the demonstrations are young, it is because most Egyptians are young.

Thinking about the way Egyptians are split about their revolution, it is interesting to see how much people offer me explicitly psychological explanations. The most simple one, regarding the switch of many of those who went out on the streets on the Friday of Anger (28 Jan) but were happy to support the president after his speech after the March of Millions (1 Feb), is that Egyptians are very emotional and prone to react emotionally, and in unpredictable ways. One of more subtle theories crystallise around the theme of Freud’s Oedipal father murder about which I wrote yesterday. Another is the Stockholm Syndrom that some have mentioned as an explanation why those who turn to support are favour of the system are often those most brutally oppressed by the same system. The Stockholm Syndrome, referring to a famous bank robbery with hostages in Stockholm, is the reaction of hostages who turn to support their abductors at whose mercy they are. There is something to it.

As I finish writing this, my plane is leaving for Frankfurt and I will be out of Egypt for a while. After these notes, I will upload also some notes from early last week which I couldn’t upload then due to lack of Internet in Egypt. Those are notes from the March of Millions on Tuesday 1 February. But unlike I was thinking at that moment, it was not the biggest demonstration in the history of Egypt. The biggest one was the Friday of Anger on 28 January when people in every street of every city went out to shout “Down with the system!” Due to the almost total media blockade by the Egyptian government, there is still much too little footage from that day. What I have seen so far, shows amazing crowds even in districts far from the city centre, but they also show very systematic violence by the police force, which shot to kill that day. Many were killed, and many more are still missing. I will try to collect image and film material from that day, and if you can send me any, your help is appreciated.

You can also see all my reports (one is still due to be uploaded later tonight) inhttp://samuliegypt.blogspot.com/ The content of the blog is in the public domain, so feel free to cite and circulate on the condition of giving credit to the original.

Greetings from revolutionary Egypt!

Samuli Schielke is a research fellow at Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), Berlin. His research focusses on everyday religiosity and morality, aspiration and frustration in contemporary Egypt. In 2006 he defended his PhD Snacks and Saints: Mawlid Festivals and the Politics of Festivity, Piety and Modernity in Contemporary Egypt at the University of Amsterdam, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences. During his stay in Cairo at the time of the protests at Tahrir Square he maintained a diary. The text here is part of that diary which you can read in full at his blog.

"Now, it's gonna be a long one" – some first conclusions from the Egyptian revolution

Posted on February 8th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: anthropology, Guest authors, Headline, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Guest Author: Samuli Schielke

Sunday, February 6, 2011

Today is my scheduled day of departure from Egypt. As I sit on Cairo airport waiting for my flight to Frankfurt, it is the first time on this trip that regret anything – I regret that I am leaving today and not staying. I have told to every Egyptian I have met today that I am not escaping, just going for my work at the university and returning soon. But perhaps it has been more to convince myself than them. My European friend who like me came here last Monday is staying for another two weeks. My American friend in Imbaba tells that for months, she has been homesick to go to America and see her parents and family again. But now when the US government would even give her a free flight, she says that she cannot go. This is her home, and she is too attached to the people, and especially to her husband. Two days ago, he was arrested on his way back from Tahrir square, held captive for four hours, interrogated, and tortured with electroshocks. He is now more determined than ever. How could she leave him behind? But today is my scheduled departure, and I only intended to come for a week and then return to do what I can to give a balanced idea of the situation in Egypt in the public debates in Germany and Finland. Tomorrow I will give a phone interview to Deutschlandradio (a German news radio), and on Tuesday I will give a talk in Helsinki in Finland. Right now, I feel that maintaining high international pressure on the Egyptian government is going to be crucial, and I will do what I can.

There remains little to be reported about the beginning day in Cairo, but maybe I can try to draw some first conclusion from this week.

The morning in Cairo today was marked by a return to normality everywhere except on Tahrir Square itself, where the demonstrations continue. Now that the streets are full with people again, the fear I felt in the past days on the streets is gone, too. If I stayed, today would be the day when I would again walk through the streets of Cairo, talk with people and feel the atmosphere.

From what I know from this morning’s short excursion in Giza and Dokki, the people remain split, but also ready to change their mind. As my Egyptian friend and I took a taxi to Dokki, the taxi driver was out on the street for the first time since 24 January, and had fully believed what the state television had told him. But as my friend, a journalist, told him what was really going on, the driver amazingly quickly shifted his opinion again, and remembered the old hatred against the oppressive system, the corruption, and the inflation that brought people to the streets last week. A big part of the people here seem impressively willing to change their mind, and if many of those who were out on the streets on 28 January – and also of those who stayed home – have changed their mind in favour of normality in the past days, they do expect things to get better now, and if they don’t, they are likely to change their minds again. This is the impression I also got from the taxi driver who took me to the airport from Dokki. He, too, had not left his house for eleven days, not out of fear for himself, but because he felt that he must stay at home to protect his family. He was very sceptical of what Egyptian television was telling, but he did expect things to get better now. What will he and others like him do if things don’t get better?

As I came to Egypt a week ago I expected that the revolution would follow one of the two courses that were marked by the events of 1989: either a successful transition to democracy by overthrowing of the old regime as happened in eastern Europe, or shooting everybody dead as happened in China. Again, my prediction was wrong (although actually the government did try the Chinese option twice, only unsuccessfully), and now something more complicated is going on.

This is really the question now: Will things get better or not? In other words: Was the revolution a success of a failure? And on what should its success be measured? If it is to be measured on the high spirits and sense of dignity of those who stood firm against the system, it was a success. If it is to be measured by the emotional switch of those who after the Friday of Anger submitted again to the mixture of fear and admiration of the president’s sweet words, it was a failure. If the immense local and international pressure on the Egyptian government will effect sustainable political change, it will be a success. But it will certainly not be an easy success, and very much continuous pressure is needed, as a friend of mine put it in words this morning: “Now, it’s gonna be a long one.”

In Dokki I visited a European-Latin American couple who are determined to stay in Egypt. He was on Tahrir Square on Wednesday night when the thugs attacked the demonstrators, and he spent all night carrying wounded people to the makeshift field hospital. He says: “What really worries me is the possibility that Mubarak goes and is replaced by Omar Suleyman who then sticks to power with American approval. He is the worst of them all.” Just in case, he is trying to get his Latin American girlfriend a visa for Schengen area, because if Omar Suleyman’s campaign against alleged “foreign elements” and “particular agendas” continues, the day may come when they are forced to leave after all.

A few words about the foreigners participating in the revolution need to be said.. Like the Spanish civil war once, so also the Egyptian revolution has moved many foreigners, mostly those living in Egypt since long, to participate in the struggle for democracy. This has been an ambiguous struggle in certain ways, because the state television has exploited the presence of foreigners on Tahrir Square in order to spread quite insane conspiracy theories about foreign agendas behind the democracy movement. The alliance against Egypt, the state television wants to make people believe, is made up of agents of Israel, Hamas, and Iran. That’s about the most insane conspiracy theory I have heard of for a long time. But unfortunately, conspiracy theories do not need to be logical to be convincing. But to step back to the ground of reality, if this revolution has taught me one thing is that the people of Egypt do not need to look up to Europe or America to imagine a better future. They have shown themselves capable of imagining a better future of their own making (with some important help from Tunisia). Compared to our governments with their lip service to democracy and appeasement of dictators, Egyptians have given the world an example in freedom and courage which we all should look up to as an example. This sense of admiration and respect is what has drawn so many foreigners to Tahrir Square in the past days, including myself.

As an anthropologist who has long worked on festive culture, I noticed a strikingly festive aspect to the revolutionary space of Tahrir Square. It is not just a protest against an oppressive regime and a demand for freedom. In itself, it is freedom. It is a real, actual, lived moment of the freedom and dignity that the pro-democracy movement demands. As such, it is an ambiguous moment, because its stark sense of unity (there is a consensus of having absolutely no party slogans on the square) and power is bound to be transient, for even in the most successful scenario it will be followed by a long period of political transition, tactics, negotiations, party politics – all kinds of business that will not be anything like that moment of standing together and finally daring to say “no!”. But thanks to its utopian nature, it is also indestructible. Once it has been realised, it cannot be wiped out of people’s minds again. It will be an experience that, with different colourings and from different perspectives, will mark an entire generation.

In a different sense, however, the relationship of transience and persistence is a critical one. A revolution is not a quick business; it requires persistence. Some have that persistence, and millions have continued demonstrating (remember that in Alexandria and all major provincial cities there are ongoing in demonstrations as well). Others, however, had the anger and energy to go out to the streets on the Friday of Anger on 28 January to say loudly “No!”, but not the persistence to withstand the lure of the president’s speech on Tuesday 1 February when Mubarak showed himself as a mortal human, an old soldier determined to die and be buried in his country. A journalist noted to me that this was the first time Mubarak has ever mentioned his own mortality – the very promise that he will die one day seems to have softened many people.

Speaking of generations, this revolution has been called a youth revolution by all sides, be it by the demonstrators themselves, the state media, or international media. Doing so has different connotations. It can mean highlighting the progressive nature of the movement, but it can also mean depicting the movement as immature. In either case, in my experience the pro-democracy movement is not really a youth movement. People of all ages support the revolution, just like there are people of all ages who oppose it or are of two minds about it. If most of the people out in the demonstrations are young, it is because most Egyptians are young.

Thinking about the way Egyptians are split about their revolution, it is interesting to see how much people offer me explicitly psychological explanations. The most simple one, regarding the switch of many of those who went out on the streets on the Friday of Anger (28 Jan) but were happy to support the president after his speech after the March of Millions (1 Feb), is that Egyptians are very emotional and prone to react emotionally, and in unpredictable ways. One of more subtle theories crystallise around the theme of Freud’s Oedipal father murder about which I wrote yesterday. Another is the Stockholm Syndrom that some have mentioned as an explanation why those who turn to support are favour of the system are often those most brutally oppressed by the same system. The Stockholm Syndrome, referring to a famous bank robbery with hostages in Stockholm, is the reaction of hostages who turn to support their abductors at whose mercy they are. There is something to it.

As I finish writing this, my plane is leaving for Frankfurt and I will be out of Egypt for a while. After these notes, I will upload also some notes from early last week which I couldn’t upload then due to lack of Internet in Egypt. Those are notes from the March of Millions on Tuesday 1 February. But unlike I was thinking at that moment, it was not the biggest demonstration in the history of Egypt. The biggest one was the Friday of Anger on 28 January when people in every street of every city went out to shout “Down with the system!” Due to the almost total media blockade by the Egyptian government, there is still much too little footage from that day. What I have seen so far, shows amazing crowds even in districts far from the city centre, but they also show very systematic violence by the police force, which shot to kill that day. Many were killed, and many more are still missing. I will try to collect image and film material from that day, and if you can send me any, your help is appreciated.

You can also see all my reports (one is still due to be uploaded later tonight) inhttp://samuliegypt.blogspot.com/ The content of the blog is in the public domain, so feel free to cite and circulate on the condition of giving credit to the original.

Greetings from revolutionary Egypt!

Samuli Schielke is a research fellow at Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), Berlin. His research focusses on everyday religiosity and morality, aspiration and frustration in contemporary Egypt. In 2006 he defended his PhD Snacks and Saints: Mawlid Festivals and the Politics of Festivity, Piety and Modernity in Contemporary Egypt at the University of Amsterdam, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences. During his stay in Cairo at the time of the protests at Tahrir Square he maintained a diary. The text here is part of that diary which you can read in full at his blog.

Verandering komt eraan? – De ‘Arabische revolte’ in Jordanië

Posted on February 5th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Gastauteur: Egbert Harmsen

Wat vele jaren lang voor onmogelijk werd gehouden lijkt nu toch bewaarheid te worden: al decennialang heersende regimes in de Arabische wereld, allen gedomineerd paternalistische en autoritaire leidersfiguren die met hun eeuwige zitvlees op de stoel van de macht blijven en die het vaak zelfs presteren om hun zoon klaar te stomen voor hun opvolging, schudden op hun grondvesten. Ook de bevolking van Jordanië is aangestoken door deze protestkoorts, die daar zoals ook elders in de Arabische wereld het geval is, wordt aangejaagd door toenemende armoede, werkloosheid en gebrek aan vrijheid en burgerrechten. Maar hoever reikt dat Jordaanse protest nu eigenlijk en wat zijn de specifieke implicaties ervan?

Het tweeledige Jordaanse protest

Het begon op 7 januari jongstleden. In het stadje Tseiban, 60 km ten zuiden van de hoofdstad Amman, gingen dagloners de straat op om te protesteren. Tegen de prijsstijgingen. Tegen de privatiseringen die in het kader van een neoliberale regeringspolitiek zijn doorgevoerd. Tegen de overheidscorruptie. Binnen een week tijd sloegen deze protesten over naar andere kleine en middelgrote steden, zoals Karak in het zuiden en Irbid in het noorden. Sociaaleconomische eisen domineerden: er moest een nieuwe regering komen die er werkelijk toe bereid was om de massawerkloosheid, de hoge prijzen en de corruptie aan te pakken. Let wel: een nieuwe regering, in de zin van een ander kabinet. Met had het niet over regime change. Aan de top van de Jordaanse machtspiramide staat immers de koning. Deze heeft over alles het laatste woord, zou boven alle partijen staan en ook boven alle misstappen en wanbeleid van overheidsfunctionarissen, tot de minister-president aan toe.

De traditionele Jordaanse oppositie wordt gedomineerd door de uit de Moslim Broederschap voortgekomen Islamitisch Actie Front Partij (IAF), bestaat verder nog uit enkele kleine linkse en seculiere pan-Arabische partijen en daarnaast uit beroepsorganisaties. Deze groepen aarzelden aanvankelijk over zijn houding ten aanzien van de bovengenoemde protesten. Deze protesten werden immers geuit door leden van Jordaanse stammen die van oudsher zeer loyaal zijn aan het Hashemitische koningshuis en diens politiek. De traditionele Jordaanse oppositiepartijen werden door de Tunesische revolutie geïnspireerd om hun stem te verheffen, maar konden op eigen houtje relatief weinig demonstranten mobiliseren. Zij zochten daarom uiteindelijk toch aansluiting bij die nieuw ontstane Jordaanse protestbeweging met zijn sociaaleconomische eisen. Deze beweging, die dus begon in Tseiban, is bekend komen te staan onder de naam “Verandering komt eraan!”. Volgens politiek analist Muhammad Abu Ruman van het Center for Strategic Studies van Jordan University te Amman probeerden de traditionele oppositiepartijen daarmee ruimte te creëren voor hun eigen politieke eisen die vooral in de sfeer lagen van meer democratie en burgerrechten. Meer concreet willen zij, onder andere, een nieuwe kieswet die gebaseerd is op evenredige vertegenwoordiging (en de regimeloyale stammen niet langer bevoordeeld), vrijheid van vergadering en een gekozen premier.

De beweging “Verandering komt eraan!” en de traditionele politieke oppositie konden elkaar vinden in de eis tot aftreden van het kabinet van premier Samir Rifai omwille van de zo hoognodige “verandering”. “Verandering komt eraan!” voelt er echter niet voor om de politieke eisen van de oppositiepartijen over te nemen. Volgens het hoofd van de beweging, Mohammad Sneid, hebben de armen in Jordanië hun eigen prioriteiten, zoals het zeker stellen van voedsel en onderdak. Het zijn zulke eisen, in de sfeer van bread and butter issues, die de beweging aan de overheid wil overbrengen. “Politieke hervormingen vullen de maag immers niet”, meent Sneid. Leiders van traditionele oppositiepartijen, zoals Saeed Thiab van de Wihdat Partij en Munir Hamarneh van de Communistische partij, staan er echter op dat politieke hervormingen, zoals de instelling van een sterk en onafhankelijk parlement die de regering werkelijk controleert en daarmee corruptie tegen gaat, noodzakelijk zijn om sociaaleconomische verbeteringen te bestendigen. De Islamisten sluiten zich bij deze zienswijze aan. In de woorden van IAF-prominent Hamza Mansour, zoals geciteerd in de Engelstalige krant Jordan Times: “we want a government chosen by the majority of the Jordanian people and we want a balance of powers; we will protest until our demands are taken seriously”.

Nieuwe regering

Het verschil in visie tussen de nieuwe protestbeweging “Verandering komt eraan!” en de traditionele oppositiepartijen brengt ook meningsverschillen omtrent de vorming van een nieuwe regering met zich mee. Eerstgenoemde beweging wenst een “regering van nationale eenheid” die afrekent met het vrije marktgeoriënteerde beleid van het kabinet van Rifai. Die nieuwe regering dient de belangen van de tribale en provinciale achterban van de beweging te behartigen in plaats van die van het grote bedrijfsleven. Eerste prioriteit daarbij is een politiek van prijsbeheersing. De islamistische en de linkse oppositiepartijen, die hun aanhang vooral in de grote steden en de Palestijnse vluchtelingenkampen hebben, staan in principe niet afwijzend tegenover deze sociaaleconomische eisen van “Verandering komt eraan!”. Ze geven er echter de voorkeur aan zelf een beslissende stem in een nieuwe regering te hebben en vinden bovendien dat het vormen van een nieuwe regering weinig zin heeft zolang het Jordaanse politieke bestel niet in structurele zin veranderd in de richting van meer democratie.

Reactie van het regime

Geschrokken door de protesten heeft het regime initiatieven ontplooid om de protesten in het land te kalmeren. Zo bracht koning Abdallah II in het diepste geheim bezoeken aan arme streken in het land. Tevens riep hij het Jordaanse parlement op om sociaaleconomische en politieke hervormingen versneld door te voeren. Dit parlement ging zich vervolgens bezinnen op maatregelen om brandstofprijzen te verlagen en de transparantie bij het vaststellen van prijzen te bevorderen. Tevens word er gesproken over het opzetten van een nationaal fonds ter ondersteuning van de armen en van industrieën die veel werkgelegenheid creëren. Salarissen van werknemers en gepensioneerden zijn verhoogd. De politie kreeg de opdracht zich te onthouden van geweld tegen demonstranten, en deelde zelfs water en vruchtensappen aan de laatstgenoemden uit. Op 1 februari jongstleden ging de koning er uiteindelijk toe over om de regering Rifai te ontslaan, naar zijn zeggen omdat dit kabinet enkel bepaalde particuliere belangen had gediend en het naliet om essentiële hervormingen door te voeren. Marouf Bakhit is nu aangewezen om premier te worden van een nieuw kabinet. Bakhit heeft een militaire achtergrond, heeft tevens een leidende rol gespeeld in het Jordaanse veiligheidsapparaat en diende van 2005 tot 2007 ook al als premier. De oppositiepartijen, de islamisten voorop, hebben geen vertrouwen in hem. Hij zou in het verleden slechts lippendienst aan politieke hervormingen hebben bewezen en in werkelijkheid iedere poging tot verdere democratisering hebben gefrustreerd. Hij wordt door islamistische leiders zelfs verantwoordelijk gehouden voor grootschalige verkiezingsfraude tijdens de parlementsverkiezingen van 2007.

“Verandering komt eraan!” is naar aanleiding van de vorming van deze nieuwe regering voorlopig gestopt met demonstraties. Het wil eerst het programma en het beleid van die regering afwachten alvorens het de protesten eventueel hervat. De traditionele oppositiepartijen, en in de eerste plaats de islamisten, willen echter doorgaan met de protesten en die nu richten tegen de nieuwe regering-Bakhit.

Een oude tweedeling

Het verschil in opvatting tussen “Verandering komt eraan!” en de traditionele oppositiepartijen weerspiegelt in hoge mate een al zeer oude tweedeling in de Jordaanse samenleving. Deze tweedeling valt in belangrijke mate samen met het onderscheid tussen de provincie en de grote stad en tot op zekere hoogte ook met die tussen autochtone Jordaanse bedoeïenenstammen en het Palestijnse bevolkingsdeel. Traditioneel worden het overheidsapparaat, de politiek en in het bijzonder het leger en het veiligheidsapparaat gedomineerd door mensen afkomstig uit bedoeïenenstammen. Onder hen bestaat er een sterk besef van loyaliteit aan het “Jordaanse vaderland” onder het gezag van het Hashemitische koningshuis. Onder de Palestijnen is er gemiddeld gesproken sprake van een veel sterkere afwijzende houding ten aanzien van de Jordaanse staat, die altijd weinig ruimte heeft geboden aan uitingen van Palestijns nationaal identiteitsbesef. De bevolking van de grotere steden van Jordanië wordt sterk door Palestijnen gedomineerd.

Palestijnen, maar ook verstedelijkte en modern opgeleide autochtone Jordaniërs hebben altijd aan de basis gestaan van oppositiebewegingen tegen het regime en zijn conservatieve en pro-westerse politiek.

In de jaren ’50 en ’60 ging het daarbij nog hoofdzakelijk om seculier pan-Arabisch nationalisme en om linkse stromingen. Lange tijd kon onvrede onder de bevolking worden afgekocht door een groeiende welvaart. Deze was in belangrijke mate het gevolg van economische steun aan Jordanië door de golfstaten en door westerse mogendheden, en van geldovermakingen naar het thuisland van Jordaanse migranten in de golfstaten. Vanaf het moment dat de olieprijzen in de jaren ’80 in een vrije val belandden was deze welvaartsgroei niet meer mogelijk en verarmden grote delen van de bevolking zelfs. Rellen die in 1989 uitbraken naar aanleiding van prijsstijgingen en bezuinigingsmaatregelen bracht de koning er uiteindelijk toe om de toenmalige regering naar huis te sturen, weer verkiezingen toe te staan en de bevolking de mogelijkheid te bieden om zijn onvrede langs democratische weg te uiten. Dit laatste mocht echter alleen gebeuren op voorwaarde dat men loyaal bleef aan Jordanië als staat en aan het gezag van het Hashemitische koningshuis. Onvrede met het regime en zijn beleid werd inmiddels vooral door de islamisten van met name de Moslim Broederschap vertolkt. Om deze islamistische invloed in te dammen werden in de loop van de jaren ‘90 burgerrechten weer in toenemende mate door het regime ingeperkt en werd het kiesstelsel aangepast. Het gevolg van die aanpassing was dat de gebieden waar de oppositie het sterkst was (de steden) ondervertegenwoordigd waren in het parlement ten gunste van de gebieden waar loyalisten woonden (rurale gebieden).

De bewoners van deze landsdelen zijn echter zeer kwetsbaar voor neoliberale economische beleidsmaatregelen op het vlak van privatisering, bezuiniging en marktwerking, aangezien zij sterk afhankelijk zijn van (werk in) de overheidssector. Dit verklaart waarom de beweging “Verandering komt eraan!”, die deze bewoners in hoge mate vertegenwoordigd, in zijn protesten de nadruk wenst te leggen op het economische beleid en minder geïnteresseerd is in democratisering van het politieke bestel. Binnen dat bestel neemt de bevolking van tribale en rurale gebieden immers tot op de dag van vandaag een bevoorrechte positie in. De islamistische en de linkse oppositie, die zijn achterban hoofdzakelijk in de politiek benadeelde grote steden heeft, wil nu juist wel streven naar democratische hervormingen.

Conclusie

De protesten in Jordanië wijken af van die in landen als Tunesië, Egypte en Jemen aangezien men hier niet zo ver gaat om het vertrek van het staatshoofd (de koning) te eisen. De demonstranten houden zich aan de in Jordanië geldende politieke spelregel dat men hooguit op specifiek beleid van de regering kritiek zou kunnen uitoefenen, maar nooit op de monarchie zelf. In die zin lijkt er weinig nieuws onder de zon vergeleken met protesten en onlusten die zich eerder in het Hashemitische koninkrijk Jordanië hebben voorgedaan. De traditionele politieke en maatschappelijke verdeeldheid in het land, die zich weerspiegelt in enerzijds de nadruk op sociaaleconomisch protest van de beweging “Verandering komt eraan!” en anderzijds de nadruk op democratische hervormingen van de traditionele islamistische en linkse oppositie, zal de hegemonie van de Hashemitische monarchie enkel in stand helpen houden. Ondertussen blijft deze monarchie zichzelf het imago aanmeten dat het boven al deze partijen staat en de belangen en het welzijn van de gehele Jordaanse natie vertegenwoordigt. Dit imago stelt de monarchie in staat om desnoods een impopulair kabinet weg te sturen, de bevolking met wat beleidsaanpassingen te kalmeren en de eigen handen schoon te wassen. Mochten de huidige ontwikkelingen in Tunesië en Egypte echter een structurele verandering in democratische zin gaan behelzen, dan is het niet uitgesloten dat ook Jordanië op een gegeven moment deze weg in zal slaan.

Egbert Harmsen heeft een achtergrond in Midden-Oosten- en Islamstudies en is daarbij gespecialiseerd in de Palestijnse kwestie, het Israëlisch-Arabische conflict, sociale en politieke islam en Jordanië. In 1995 studeerde hij af op een doctoraalscriptie over de opvang en integratie van Palestijnen in Jordanië die tijdens en na de Golfcrisis en -oorlog van 1990/91 Koeweit waren ontvlucht. In 2007 promoveerde hij op een dissertatie getiteld “Islam, Civil Society and Social Work, the Case of Muslim NGOs in Jordan”. Na zijn promotie verichtte hij onderzoek naar islam en moslims in Nederland. Momenteel is hij werkzaam als Universitair Docent Midden-Oosten Studies aan de Universiteit Leiden.

Two Faces of Revolution

Posted on February 1st, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Featured, Guest authors, Headline, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Guest Author: Linda Herrera

Mohamed Bouazizi

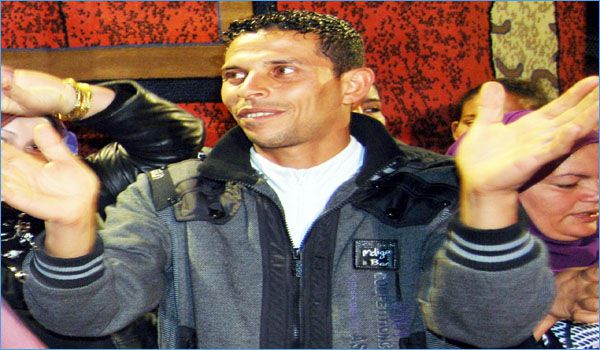

Khaled Said

The events in Tunisia and Egypt have riveted the region and the world. The eruptions of people power have shaken and taken down the seeming unbreakable edifices of dictatorship. (At the time of writing Mubarak has not formally acknowledged that he has been toppled, but the force of the movement is too powerful and determined to fathom any other outcome). Events are moving at breakneck speed and a new narrative for the future is swiftly being written. In the throes of a changing future it merits returning to the stories of two young men, the two faces that stoked the flames of revolution thanks to the persistence of on-line citizen activists who spread their stories. For in the tragic circumstances surrounding their deaths are keys to understanding what has driven throngs of citizens to the streets.

Mohammed Bouazizi has been dubbed “the father of Arab revolution”; a father indeed despite his young years and state of singlehood. Some parts of his life are by now familiar. This 26 year old who left school just short of finishing high school (he was NOT a college graduate as many new stories have been erroneously reporting) and worked in the informal economy as a vendor selling fruits and vegetable to support his widowed mother and five younger siblings. Overwhelmed by the burden of fines, debts, the humiliation of being serially harassed and beaten by police officers, and the indifference of government authorities to redress his grievances, he set himself on fire. His mother insists that though his poverty was crushing, it was the recurrence of humiliation and injustice that drove him to take his life. The image associated with Mohammed Bouazizi is not that of a young man’s face, but of a body in flames on a public sidewalk. His self-immolation occurred in front of the local municipal building where he sought, but never received, justice.

The story of 28 year old Egyptian, Khaled Said, went viral immediately following his death by beating on June 6, 2010. Two photos of him circulated the blogosphere and social networking sites. One was a portrait of his gentle face and soft eyes coming out of a youthful grey hooded sweatshirt; the face of an everyday male youth. The accompanying photo was of the bashed and bloodied face on the corpse of a young man. Though badly disfigured, the image held enough resemblance to the pre-tortured Khaled to decipher that the two faces belonged to the same person. The events leading to Khaled’s killing originated when he posted a video of two police officers allegedly dividing the spoils of a drug bust. This manner of citizen journalism has become commonplace since 2006. Youths across the region have been emboldened by a famous police corruption case of 2006. An activist posted a video on YouTube of two police officers sodomizing and whipping a minibus driver, Emad El Kabeer. It not only incensed the public and disgraced the perpetrators, but led to their criminal prosecution. On June 6, 2010, as Khaled Said was sitting in his local internet café in Alexandria two policemen accosted him and asked him for his I.D. which he refused to produce. They proceeded to drag him away and allegedly beat him to his death as he pleaded for his life. The officers claimed that Khaled died of suffocation when he tried to swallow a package of marijuana to conceal drug possession. But the power of photographic evidence combined with eyewitness accounts and popular knowledge of scores of cases of police brutality left no doubt in anyone’s mind that he was senselessly and brutally murdered by the very members of the police that were supposed to protect them. The court case of the two officers is ongoing.

Mohammed Bouazizi was not the first person to resort to suicide by self immolation out of desperation, there has been an alarming rise in such incidents in different Arab countries. And Khaled Said is sadly one of scores of citizens who have been tortured, terrorized, and killed by police with impunity. But the stories of these two young men are the ones that have captured the popular imagination, they have been game changers.

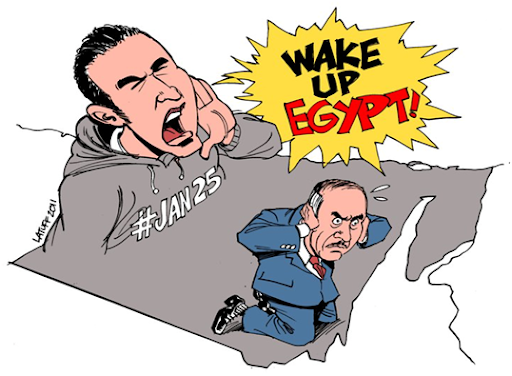

Cartoon from the Facebook Group We are all Khaled Said*

For the youth of Egypt and Tunisia, the largest cohort of young people ever in their countries, the martyrdoms of Khaled Said and Mohamed Bouaziz represent an undeniable tipping point, the breaking of the fear barrier. The youth have banned together as a generation like never before and are crying out collectively, “enough is enough!” to use the words of a 21 year old friend, Sherif, from Alexandria. The political cartoon of Khaled Said in his signature hoodie shouting to the Intelligence Chief, also popularly known “Torturer in chief” and now Mubarak’s Vice President, to “wake up Egypt” perfectly exemplifies this mood (from the Facebook group, We are all Khaled Said). No longer will the youth cower to authority figures tainted by corruption and abuses. These illegitimate leaders will cower to them. The order of things will change.

And so on January 25, 2011, inspired by the remarkable and inspiring revolution in Tunisia that toppled the twenty-three year reign of the dictatorship of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Egyptian youth saw it was possible to topple their dictator, Hosni Mubarak, of 31 years. Activists used different on-line platforms, most notably the April 6 Youth Movement and the “We are all Khaled Said” Facebook group to organize a national uprising against “Torture, Corruption, Poverty, and Unemployment.”

It is not arbitrary that civil rights, as exemplified in torture and corruption (recall Khaled Said), topped the list of grievances, followed by economic problems. For youth unemployment and underemployment will, under any regime, be among the greatest challenges of the times.

Banner of the Egyptian uprising

No one could have anticipated that this initial call would heed such mass and inclusive participation. Youths initially came to the streets braving tanks, rubber bullets, tear gas (much of which is made in the US and part of US military aid, incidentally), detention, and even death. And they were joined by citizens of all persuasions and life stages; children, youth, elderly, middle aged, female, male, middle class, poor, Muslim, Christians, Atheists.

Contrary to a number of commentators in news outlets in North America and parts of Europe the two revolutions overtaking North Africa are not motivated by Islamism and there are no compelling signs that they will be co-opted in this direction. Such analyses are likely to be either ideologically driven or misinformed. In fact, Islam has not figured whatsoever into the stories of Bouazizi and Said. These are inclusive freedom movements for civic, political, and economic rights. To understand what is driving the movement and what will invariably shape the course of reforms in the coming period we need to return to these young men. Their evocative if tragic deaths speak reams about the erosion of rights and accountability under decades of corrupt dictatorship, about the rabid assault on people’s dignity. They remind us of the desperate need to restore a political order that is just and an economic order that is fair. Mohamed Bouazizi and Khaled Said have unwittingly helped to pave a way forward, and to point the way to the right side of history.

*Correction: The figure who appears cowering in the cartoon is former Minister of Interior, Habib al-Adly, NOT Omar Suleiman, Mubarak’s VP

Linda Herrera is a social anthropologist with expertise in comparative and international education. She has lived in Egypt and conducted research on youth cultures and educational change in Egypt and the wider Middle East for over two decades. She is currently Associate Professor, Department of Education Policy, Organization and Leadership, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is co-editor with A. Bayat of the volume Being Young and Muslim: New Cultural Politics in the Global North and South, published by Oxford University Press (2010).

This post also appeared at Thetyee.ca

‘Telefoon uit Tunesië’ – Een persoonlijk verslag van de Jasmijn-revolutie

Posted on January 29th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Gastauteur: Carpe D.M.

Tunesië, in de ogen van de westerse wereld een zonnig vakantieland en een voorbeeld van hoe een Arabisch land zou moeten zijn. Een vrij land, een modern land, een land waar de islam een rol speelt, maar niet de hoofdrol. Wij Tunesiers weten dat niets minder waar is. Tunesië wordt al jaren geregeerd door de president Zine al Abedine Ben Ali, een president die al jarenlang ‘democratisch’ wordt gekozen. Hij is de opvolger van president Habib Bourguiba , onder zijn bewind was Ben Ali generaal van het leger. In 1987 greep Ben Ali de macht. Hij is getrouwd met Leila Trabelsi, een kapster. De familie Trabelsi is de meeste gehate en gevreesde familie binnen Tunesië. Bijna alle bedrijven zijn in hun handen, zij zijn verantwoordelijk voor alle drugs in- en export, hebben de volledige alcoholmarkt in handen (inclusief fabrieken) en wil je iets gedaan krijgen, moet jouw geld die kant op.

Dit alles was onzichtbaar voor de buitenwereld, totdat op 17 december 2010 de waarheid beetje bij beetje naar buiten kwam. Mohammed Bouazizzi, een jongen zoals alle anderen, afgestudeerd als ICTer en werkloos. Hij besloot het er niet bij te laten zitten en startte zijn eigen groente- en fruitkraam om op deze legitieme manier toch geld te kunnen verdienen voor zijn familie. Maandenlang probeerde hij een vergunning te krijgen, maar vanwege de corruptie van het land werd dit hem onmogelijk gemaakt. Het probleem in Tunesië is dat ambtenaren te pas en te onpas geld willen zien om in eigen zak te steken, en de bedragen zijn zo hoog, dat niemand dit kan betalen. Hij ging verhaal halen op het gemeentehuis en bij terugkomst was zijn kar weggesleept. Uit pure wanhoop stak hij zichzelf in brand. Hij belandde in het ziekenhuis in coma, en overleed een paar dagen later. Wat volgde op zijn daad was iets dat hij in zijn stoutste dromen niet had durven dromen. Het land besloot zijn dood niet voor niets te laten zijn, en kwam in opstand. Wekenlang gingen jongeren de straat op om te demonstreren voor hun rechten.

Tunesië zou Tunesië niet zijn als dit niet keihard de kop ingedrukt zou worden. Het leger en politieagenten werden door Ben Ali ingezet om de mensen terug te dringen en de mond te snoeren, zelfs te doden. Het begon in het dorp Sidi Bouzid en ging vanaf daar door naar de stad Kasserine; in deze stad alleen al vielen minimaal 50 doden door het harde optreden van de politie. Vanuit daar trok de onrust verder het land in, met als eindbestemming het dorp Bizerte en de hoofdstad Tunis. Donderdag 16 januari 2011 kreeg ik ’s ochtends een telefoontje van mijn zestienjarige nichtje, huilend. Mijn oom, tante, nichtjes en neefjes hadden al twee dagen niet gegeten omdat de supermarkten uitgebrand waren en binnen een uur zou het water afgesloten worden. Kort na dit bericht werd inderdaad bekend dat de regering het water en de elektriciteit zou gaan afsluiten. Het water om de mensen tot wanhoop te drijven, en de elektriciteit om zowel de telefoonlijn als het internet af te sluiten, zodat contact met de buitenwereld onmogelijk zou worden.

Over de hele wereld begonnen Tunesiërs vanuit tientallen landen in actie te komen, voornamelijk door middel van demonstraties. Zó ook in Nederland. De avond dat de voorbereidingen getroffen werden kwam plotseling een onverwachte persconferentie van Ben Ali. Zijn beloftes: vanaf dit moment zou er een vrijheid van meningsuiting gelden, er zouden miljoenen gepompt worden in de economie om zo de werkgelegenheid te stimuleren, YouTube zou opengezet worden, er zou geen geweld meer gebruikt worden tegen de demonstranten én de prijzen van brood, suiker en melk zouden naar beneden gaan. Dit alles leidde binnen één uur tot grote verbazing (voornamelijk onder de Tunesiërs die woonachtig zijn buiten Tunesië) en tot grote vreugde. Binnen een uur reden tientallen auto’s al toeterend de straten op, klonken er leuzen als ‘lang leve Ben Ali’ en werden er honderden YouTube filmpjes op Facebook ge-upload. Dit alles tot grote verbazing van de Tunesiërs uit de Nederlandse gemeenschap. Waren hier al die mensen voor gestorven? Waren ze nu al vergeten wat dit regime met het land had gedaan? Beseften zij niet dat dit loze beloftes waren? Met stomheid geslagen werd er druk gediscussieerd of de demonstratie nog wel door moest gaan. Verdienden ze al deze steun en moeite nog wel?

De volgende ochtend werd bekend gemaakt dat twee uur na de speech het wederom uit de hand was gelopen en er drie mensen waren doodgeschoten. Daarnaast bleek dat Ben Ali politieagenten in burger de straat op had gestuurd om naar de buitenwereld toe de illusie te wekken dat hij de situatie weer onder controle had. Vrijdag 14 januari begonnen er ’s ochtends vroeg weer (vreedzame) demonstraties, tot de politie rond het middaguur wederom met geweld ingreep en de situatie uit de hand liep. Die dag heeft (ex)president Ben Ali besloten tijdelijk het land te ontvluchten samen met zijn vrouw, en zijn werkzaamheden over te dragen aan Mohammed Ghannouchi. Ben Ali vluchtte, in de eerste instantie richting Malta, waar hem de toegang werd ontzegd. Vervolgens Parijs en Dubai, maar ook daar werd hij niet ontvangen. Hij is nu al twee weken woonachtig in Saudi-Arabië, het land dat hem wel als politiek vluchteling heeft onthaald.

Zaterdag 15 januari zijn er drie gevangenissen in brand gestoken. Enkelen zijn vermoord, maar zo’n 3000 gevangenen hebben de gevangenissen kunnen ontvluchten. Zij zijn het land ingetrokken om het land verder in vernieling te brengen, geweld te plegen en overvallen te plegen. Online werden beelden geplaatst van politieagenten die ook massaal winkels plunderden en banken overvielen. Mijn vriendin, woonachtig in Tunis liet over FaceBook weten dat iedereen doodsbang was, omdat politieagenten huizen openbraken om spullen te stelen en de meisjes en vrouwen te verkrachten. Nadat het leger dit doorkreeg ontstonden er vuurgevechten tussen het leger en de politietroepen. Het leger heeft de hele periode aan de kant van het volk gestaan en heeft alles op alles gezet om de orde te handhaven.

Direct nadat de president het land verliet en zijn rechterhand de macht over het land had gegeven, trokken de demonstranten de straten weer op om iedereen binnen het kabinet die lid was van de RCD –de partij van Ben Ali- de interim regering te doen verlaten. Uiteindelijk is Ghannouchi vertrokken als interim president en zijn de werkzaamheden overgedragen aan de voorzitter van het parlement, zoals in de grondwet is vastgelegd. Wel is hij aangebleven als lid van de regering. Ben Ali wilde in eerste instantie terugkeren naar het land, maar heeft op advies van andere regeringsleiders te kennen gegeven dat hij definitief zijn troon heeft verlaten en er binnen twee maanden verkiezingen gaan plaats vinden.