9.00-9.30

Registratie

9.30-9.35

Opening Thijl Sunier (VU)

9.35-10.30

Keynote Tobias Kelly (University of Edinburgh)

The Integrity of Conscience? Commitments, Doubts and Pacifism.

10.30-11.00

Koffie en thee

11.00-12.30

Panel 1 & Panel 2

Panel 1

Wie controleert de antropoloog? (I)

Een gesprek over fraude, integriteit en antropologie.

Hoe wordt er binnen de discipline gedacht over fraude, integriteit en controleerbaarheid?

Voorzitter: Anouk de Koning (Radboud)

Gespreksleider: Rivke Jaffe (UvA)

Sprekers:

- Janneke Verheijen (Radboud) vertelt waarom ze al haar veldwerkdata online heeft gezet.

- Sjaak van der Geest (UvA) doet een boekje open over zijn eigen ‘zonden’ om zo de discussie over integriteit binnen antropologie op scherp te zetten.

- Henk Driessen (Radboud) gaat in op de kwesties informed consent, small talk en de ‘fly on the wall’ positie. Wat voor consequenties heeft dit voor het denken over integriteit in antropologie?

- Maja Lovrenovic (VU) doet zelf onderzoek in het gebied waar Mart Bax werkte. Zij reflecteert op de implicaties van Mart Bax’ fraude voor antropologie.

Panel 2

Veldwerk, sociale media en ethiek

Facebook, forumdiscussies, weblogs en video’s zijn tegenwoordig een vast onderdeel van antropologisch veldwerk. Deze nieuwe communicatiemiddelen roepen ook nieuwe ethische vragen op over de anonimiteit van respondenten, de relatie tussen onderzoeker en onderzochten en over wat privé en publiek is. In dit panel zullen drie antropologen vanuit de praktijk van hun veldwerk verschillende ethische dilemma’s ter discussie stellen.

Voorzitter: Lenie Brouwer (VU)

Sprekers:

- Marloes Hamelinck (UU): moslimvrouwen en sociale media op Zanzibar. Hamelinck heeft onderzoek gedaan naar het sociaal media gebruik van moslimvrouwen op Zanzibar en hoe dit gebruik in relatie staat tot morele kwesties. Zij richt zich vooral op de rol van religie in het dagelijks leven en op het gebruik van onder andere Facebook. Zij vraagt zich af hoe je Facebook en online discussies als onderzoeksmateriaal kunt gebruiken. Hoe kun je de anonimiteit van informanten waarborgen? En hoe informeer je informanten?

- Anke Tonnaer (Radboud): reisweblobgs en toerisme. Tonnaer houdt zich bezig met toerisme en vraagt zich af wat te doen met alle reisblogs die mensen op het web plaatsen. Hoe kun je hier op een ethisch verantwoorde manier mee omgaan?

- Fridus Steijlen (KITLV): video’s en het dagelijks leven in Indonesië. Steijlen houdt zich al jaren bezig met het filmen van het dagelijks leven op bepaalde plekken in Indonesie. Hij loopt hierbij tegen vragen aan die betrekking hebben op de privacy van de mensen, zowel in het privé als publieke domein. En hoe open en toegankelijk mag en kan het materiaal zijn? Tenslotte, een belangrijk punt van aandacht is dat privacy altijd cultureel bepaald is.

12.30-13.30

Lunch

13.30-15.00

Panel 3 & Panel 4

Panel 3

Wie controleert de antropoloog? (II)

Een gesprek over facultaire richtlijnen en antropologische tactieken.

Wat voor gevolgen hebben diverse integriteitsrichtlijnen en -protocollen voor de verschillende antropologie-afdelingen en hoe gaan antropologen hiermee om?

Voorzitter: Thijl Sunier (VU)

Sprekers:

- Katrien Klep (Utrecht)

- Toon van Meijl (Radboud)

- Overige sprekers worden nog bekend gemaakt.

Panel 4

Veranderend werkveld, nieuwe ethische vragen.

Wat voor ethische kwesties komen naar voren in de nieuwe velden waarin antropologen werkzaam zijn? Wat is, bijvoorbeeld, de ethische manier om samen te werken met mijnbouwbedrijven? En wat voor ethische dilemma’s kom je tegen als organisatieantropoloog?

Voorzitter: Roxane Beumer (Focus)

Sprekers:

- Sabine Luning (Unversiteit Leiden)

- Jacqueline Franssens (Culture at Work)

- Siela Ardjosemito-Jethoe is cultureel antropoloog/sociologisch onderzoeker en docent aan de Haagse Hogeschool en actief met eigen adviesbureau DieVersheid. Vanuit DieVersheid focust zij zich op diversiteitsvraagstukken in de zorg-, welzijn- en educatiesector. Zij gaat in haar presentatie in op haar etnografische onderzoek naar gender in de multiculturele klas van vandaag en vertelt over haar worsteling met haar rol als onderzoeker vs haar rol als docent.

- Wim Manahutu heeft als directeur van het Moluks Historisch Museum met ethiek en de dilemma’s van (antropologisch) onderzoek en de representatie en zelf-representatie van culturele/etnische groepen te maken gehad.

- Hij bespreekt hoe de erfgoedsector zich verhoudt tot ontwikkelingen in de maatschappij.

15.00-15.30

Koffie en thee

15.30-17.00

Panel 5 & Panel 6

Panel 5

Politics, ethics and fieldwork.

Welke ethische kwesties kom je tegen als je je als antropoloog met studying-up bezig houdt, of in een politiek mijnenveld begeeft? In dit panel bespreken we de ethische dilemma’s in onderzoek naar Nederlandse salafisten, game farms in Zuidelijk Afrika, en in de relatie met een conservatieve politica in Mexico.

Voorzitter: Anouk de Koning (Radboud)

Sprekers:

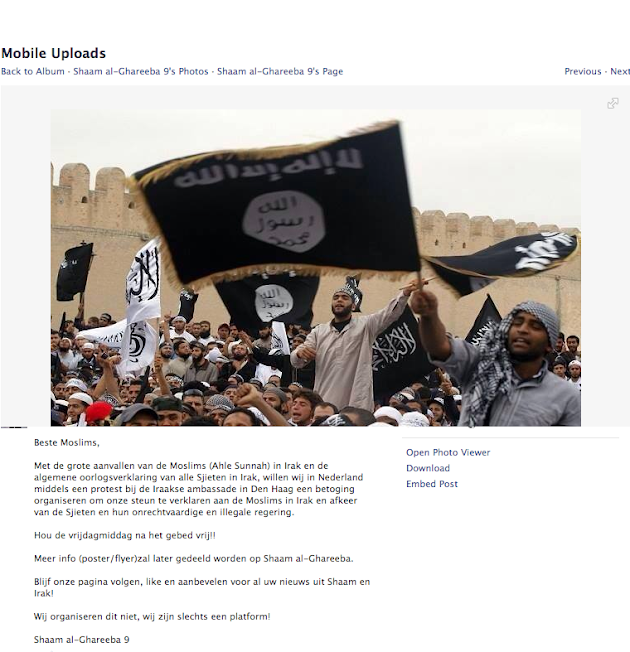

- Martijn de Koning (UvA/Radboud)

Between a game of football and Jihadi Da’wa in the streets of The Hague — The limits of online and offline fieldwork with militant networks.

“In 2012 I started a new research project together with two colleagues. The Public Islamic Mission (PIM) project focused on groups of Muslim militants who affiliated themselves with the ideology of Al Qaeda and, in various ways, showed support for the implementation of sharia laws in the countries where they were based: the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. In this paper I will concentrate on my research among the Dutch groups and take up three issues: how does a new socio-political context create new strategic and ethical questions? What are the consequences of dealing with groups that many people in society regard as repulsive and dangerous? Where and how to draw the boundaries of participant observation? I will in particular focus on the relation between strategic, ethical and political issues. The paper is based on online and offline fieldwork.”

- Marja Spierenburg (VU/CERES)

How multi-stakeholder is your multi-stakeholder workshop? Politics and power in stakeholder engagement in research.

“This presentation addresses the assumptions underlying stakeholder engagement in the planning and conducting of research, as well as in the dissemination of research findings. Funding agencies increasingly demand such engagement, assuming that multi-stakeholder platforms are neutral spaces for negotiation about research questions and the translation of research findings in policy-recommendations. Based on experiences with a research programme investigating the social impacts of conversions of farms to private wildlife conservation areas in South Africa, this presentation discusses the promises and pitfalls of stakeholder engagement in research. The presentation focuses on the power relations between the major stakeholders involved – (mainly white) farm owners and managers; farm workers and dwellers; NGOs representing farm dwellers; and government officials – and their differential access to the policy-making arena. The presentation furthermore addresses how these different groups tried to influence both the research questions as well as the outcomes of the research.”

- Tine Davids (Radboud)

Trying to be a vulnerable observer

“In this article, I seek to further explore my engagements with Mexican female politicians. This encounter with these – in particular right-wing – women has not only led to me having a different understanding of agency, but has also caused me to critically examine the practice of conducting feminist research. Can feminist solidarity be encountered and critical standards met in research on conservative women? What kind of engagement or common ground can be found in this inter-subjective and transnational space, connecting myself as researcher to the Mexican women under study?”

Discussant: Tobias Kelly (University of Edinburgh)

Panel 6

LASSA panel: Ethische dillema’s onder studenten op veldwerk

Studenten komen tijdens hun studie verschillende ethische dilemma’s tegen, met name tijdens het veldwerk. Deze dilemma’s zijn ook nog eens erg divers. Waar ligt de grens tussen informant en vriendschap? Hoe ga ik om met mijn data? In hoeverre pas ik mijn onderzoek aan aan de wensen van de organisatie waarbij ik onderzoek doe? Tijdens het studentenpanel gaan we verder in op dergelijke vragen, die steeds belangrijker worden voor studenten.

Voorzitter: Jelte Verberne (Utrecht)

Sprekers:

- Renske den Uil (VU)

- Maartje van der Zedde (UvA)

- Anne de Jonghe (UU)

17.00-17.15

Afsluiting door Ton Salman (VU)

17.15

Borrel

Kom luisteren en discussieer mee over antropologie, integriteit en ethiek. Aanmelden kan via

secretaris@antropologen.nl

. In verband met de catering verzoeken wij iedereen zich voor 6 juni aan te melden.

De toegangsprijs voor de dag is inclusief toegang tot het museum, koffie/thee, lunch en de borrel na afloop.

- Studentleden: 15 euro

- Overige leden: 25 euro

- Niet-leden studenten: 30 euro

- Overige niet-leden: 45 euro

Vanwege het beperkte aantal plaatsen, is het aan te raden om vooraf te registreren.

N.B. Het is mogelijk ter plekke lid te worden van het ABv en de ledenprijs te betalen. Lidmaatschap voor studenten is 25 euro, voor anderen 45 euro per jaar. Leden krijgen twee keer per jaar het antropologisch tijdschrift Etnofoor thuisgestuurd.