| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Sep | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

Pages

- About

- C L O S E R moves to….C L O S E R

- Contact Me

- Interventions – Forces that Bind or Divide

- ISIM Review via Closer

- Publications

- Research

Categories

- (Upcoming) Events (33)

- [Online] Publications (26)

- Activism (117)

- anthropology (113)

- Method (13)

- Arts & culture (88)

- Asides (2)

- Blind Horses (33)

- Blogosphere (192)

- Burgerschapserie 2010 (50)

- Citizenship Carnival (5)

- Dudok (1)

- Featured (5)

- Gender, Kinship & Marriage Issues (265)

- Gouda Issues (91)

- Guest authors (58)

- Headline (76)

- Important Publications (159)

- Internal Debates (275)

- International Terrorism (437)

- ISIM Leiden (5)

- ISIM Research II (4)

- ISIM/RU Research (171)

- Islam in European History (2)

- Islam in the Netherlands (219)

- Islamnews (56)

- islamophobia (59)

- Joy Category (56)

- Marriage (1)

- Misc. News (891)

- Morocco (70)

- Multiculti Issues (749)

- Murder on theo Van Gogh and related issues (326)

- My Research (118)

- Notes from the Field (82)

- Panoptic Surveillance (4)

- Public Islam (244)

- Religion Other (109)

- Religious and Political Radicalization (635)

- Religious Movements (54)

- Research International (55)

- Research Tools (3)

- Ritual and Religious Experience (58)

- Society & Politics in the Middle East (159)

- Some personal considerations (146)

- Deep in the woods… (18)

- Stadsdebat Rotterdam (3)

- State of Science (5)

- Twitwa (5)

- Uncategorized (74)

- Young Muslims (459)

- Youth culture (as a practice) (157)

General

- ‘In the name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful’

- – Lotfi Haddi –

- …Kelaat Mgouna…….Ait Ouarchdik…

- ::–}{Nour Al-Islam}{–::

- Al-islam.nl De ware godsdienst voor Allah is de Islam

- Allah Is In The House

- Almaas

- amanullah.org

- Amr Khaled Official Website

- An Islam start page and Islamic search engine – Musalman.com

- arabesque.web-log.nl

- As-Siraat.net

- assadaaka.tk

- Assembley for the Protection of Hijab

- Authentieke Kennis

- Azaytouna – Meknes Azaytouna

- berichten over allochtonen in nederland – web-log.nl

- Bladi.net : Le Portail de la diaspora marocaine

- Bnai Avraham

- BrechtjesBlogje

- Classical Values

- De islam

- DimaDima.nl / De ware godsdienst? bij allah is de islam

- emel – the muslim lifestyle magazine

- Ethnically Incorrect

- fernaci

- Free Muslim Coalition Against Terrorism

- Frontaal Naakt. Ongesluierde opinies, interviews & achtergronden

- Hedendaagse wetenswaardigheden…

- History News Network

- Homepage Al Nisa

- hoofddoek.tk – Een hoofddoek, je goed recht?

- IMRA: International Muslima Rights Association

- Informed Comment

- Insight to Religions

- Instapundit.com

- Interesting Times

- Intro van Abdullah Biesheuvel

- islaam

- Islam Ijtihad World Politics Religion Liberal Islam Muslim Quran Islam in America

- Islam Ijtihad World Politics Religion Liberal Islam Muslim Quran Islam in America

- Islam Website: Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic, Religion

- Islamforum

- Islamic Philosophy Online

- Islamica Magazine

- islamicate

- Islamophobia Watch

- Islamsevrouw.web-log.nl

- Islamwereld-alles wat je over de Islam wil weten…

- Jihad: War, Terrorism, and Peace in Islam

- JPilot Chat Room

- Madrid11.net

- Marocstart.nl – De marokkaanse startpagina!

- Maryams.Net – Muslim Women and their Islam

- Michel

- Modern Muslima.com

- Moslimjongeren Amsterdam

- Moslimjongeren.nl

- Muslim Peace Fellowship

- Muslim WakeUp! Sex & The Umma

- Muslimah Connection

- Muslims Against Terrorism (MAT)

- Mutma’inaa

- namira

- Otowi!

- Ramadan.NL

- Religion, World Religions, Comparative Religion – Just the facts on the world\’s religions.

- Ryan

- Sahabah

- Salafi Start Siden – The Salafi Start Page

- seifoullah.tk

- Sheikh Abd al Qadir Jilani Home Page

- Sidi Ahmed Ibn Mustafa Al Alawi Radhiya Allahu T’aala ‘Anhu (Islam, tasawuf – Sufism – Soufisme)

- Stichting Vangnet

- Storiesofmalika.web-log.nl

- Support Sanity – Israel / Palestine

- Tekenen van Allah\’s Bestaan op en in ons Lichaam

- Terrorism Unveiled

- The Coffee House | TPMCafe

- The Inter Faith Network for the UK

- The Ni’ma Foundation

- The Traveller’s Souk

- The \’Hofstad\’ terrorism trial – developments

- Thoughts & Readings

- Uitgeverij Momtazah | Helmond

- Un-veiled.net || Un-veiled Reflections

- Watan.nl

- Welkom bij Islamic webservices

- Welkom bij vangnet. De site voor islamitische jongeren!

- welkom moslim en niet moslims

- Yabiladi Maroc – Portail des Marocains dans le Monde

Dutch [Muslims] Blogs

- Hedendaagse wetenswaardigheden…

- Abdelhakim.nl

- Abdellah.nl

- Abdulwadud.web-log.nl

- Abou Jabir – web-log.nl

- Abu Bakker

- Abu Marwan Media Publikaties

- Acta Academica Tijdschrift voor Islam en Dialoog

- Ahamdoellilah – web-log.nl

- Ahlu Soennah – Abou Yunus

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Al Moudjahideen

- Al-Adzaan

- Al-Islaam: Bismilaahi Rahmaani Rahiem

- Alesha

- Alfeth.com

- Anoniempje.web-log.nl

- Ansaar at-Tawheed

- At-Tibyan Nederland

- beni-said.tk

- Blog van moemina3 – Skyrock.com

- bouchra

- CyberDjihad

- DE SCHRIJVENDE MOSLIMS

- DE VROLIJKE MOSLIM ;)

- Dewereldwachtopmij.web-log.nl

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Eali.web-log.nl

- Een genade voor de werelden

- Enige wapen tegen de Waarheid is de leugen…

- ErTaN

- ewa

- Ezel & Os v2

- Gizoh.tk [.::De Site Voor Jou::.]

- Grappige, wijze verhalen van Nasreddin Hodja. Turkse humor.

- Hanifa Lillah

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Het laatste nieuws lees je als eerst op Maroc-Media

- Homow Universalizzz

- Ibn al-Qayyim

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- Islam Blog – Juli 2007

- Islam in het Nieuws – web-log.nl

- Islam, een religie

- Islam, een religie

- Islamic Sisters – web-log.nl

- Islamiway’s Weblog

- Islamtawheed’s Blog

- Jihaad

- Jihad

- Journalista

- La Hawla Wa La Quwatta Illa Billah

- M O S L I M J O N G E R E N

- M.J.Ede – Moslimjongeren Ede

- Mahdi\’s Weblog | Vrijheid en het vrije woord | punt.nl: Je eigen gratis weblog, gratis fotoalbum, webmail, startpagina enz

- Maktab.nl (Zawaj – islamitische trouwsite)

- Marocdream.nl – Home

- Marokkaanse.web-log.nl

- Marokkanen Weblog

- Master Soul

- Miboon

- Miesjelle.web-log.nl

- Mijn Schatjes

- Moaz

- moeminway – web-log.nl

- Moslima_Y – web-log.nl

- mosta3inabilaah – web-log.nl

- Muhaajir in islamitisch Zuid-Oost Azië

- Mumin al-Bayda (English)

- Mustafa786.web-log.nl

- Oprecht – Poort tot de kennis

- Said.nl

- saifullah.nl – Jihad al-Haq begint hier!

- Salaam Aleikum

- Sayfoudien – web-log.nl

- soebhanAllah

- Soerah19.web-log.nl – web-log.nl

- Steun Palestina

- Stichting Moslimanetwerk

- Stories of Malika

- supermaroc

- Ummah Nieuws – web-log.nl

- Volkskrant Weblog — Alib Bondon

- Volkskrant Weblog — Moslima Journalista

- Vraag en antwoord…

- wat is Islam

- Wat is islam?

- Weblog – a la Maroc style

- website van Jamal

- Wij Blijven Hier

- Wij Blijven Hier

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- www.moslima.web-log.nl

- Yakini Time

- Youth Of Islam

- Youth Of Islam

- [fikra]

Non-Dutch Muslims Blogs

- Lanallah __Islamic BlogZine__

- This journey ends but only with The Beginning

- ‘the middle place’

- …Never Judge a Person By His or Her Blog…

- …under the tree…

- A Comment on PMUNA

- A Dervish’s Du`a’

- A Family in Baghdad

- A Garden of Children

- A Muslim Mother’s Thoughts / Islamic Parenting

- A Struggle in Uncertainty, Such is Life

- About Afghanistan

- adnan.org: good design, bad idea

- Afiyah

- Ahmeds World of Islam

- Al Musawwir

- Al-Musharaka

- Almiraya tBLOG – O, happy the soul that saw its own faults

- Almusawwir

- an open window

- Anak Alam

- aNaRcHo AkBaR

- Anthology

- AnthroGal’s World

- Arabian Passion

- ArRihla

- Articles Blog

- Asylum Seeker

- avari-nameh

- Baghdad Burning

- Being Noor Javed

- Bismillah

- bloggin’ muslimz.. Linking Muslim bloggers around the globe

- Blogging Islamic Perspective

- Chapati Mystery

- City of Brass – Principled pragmatism at the maghrib of one age, the fajr of another

- COUNTERCOLUMN: All Your Bias Are Belong to Us

- d i z z y l i m i t s . c o m >> muslim sisters united w e b r i n g

- Dar-al-Masnavi

- Day in the life of an American Muslim Woman

- Don’t Shoot!…

- eat-halal guy

- Eye on Gay Muslims

- Eye on Gay Muslims

- Figuring it all out for nearly one quarter of a century

- Free Alaa!

- Friends, Romans, Countrymen…. lend me 5 bux!

- From Peer to Peer ~ A Weblog about P2P File & Idea Sharing and More…

- Ghost of a flea

- Ginny’s Thoughts and Things

- God, Faith, and a Pen: The Official Blog of Dr. Hesham A. Hassaballa

- Golublog

- Green Data

- gulfreporter

- Hadeeth Blog

- Hadouta

- Hello from the land of the Pharaoh

- Hello From the land of the Pharaohs Egypt

- Hijabi Madness

- Hijabified

- HijabMan’s Blog

- Ihsan-net

- Inactivity

- Indigo Jo Blogs

- Iraq Blog Count

- Islam 4 Real

- Islamiblog

- Islamicly Locked

- Izzy Mo’s Blog

- Izzy Mo’s Blog

- Jaded Soul…….Unplugged…..

- Jeneva un-Kay-jed- My Bad Behavior Sanctuary

- K-A-L-E-I-D-O-S-C-O-P-E

- Lawrence of Cyberia

- Letter From Bahrain

- Life of an American Muslim SAHM whose dh is working in Iraq

- Manal and Alaa\’s bit bucket | free speech from the bletches

- Me Vs. MysElF

- Mental Mayhem

- Mere Islam

- Mind, Body, Soul : Blog

- Mohammad Ali Abtahi Webnevesht

- MoorishGirl

- Muslim Apple

- muslim blogs

- Muslims Under Progress…

- My heart speaks

- My Little Bubble

- My Thoughts

- Myself | Hossein Derakhshan’s weblog (English)

- neurotic Iraqi wife

- NINHAJABA

- Niqaabi Forever, Insha-Allah Blog with Islamic nasheeds and lectures from traditional Islamic scholars

- Niqabified: Irrelevant

- O Muhammad!

- Otowi!

- Pak Positive – Pakistani News for the Rest of Us

- Periphery

- Pictures in Baghdad

- PM’s World

- Positive Muslim News

- Procrastination

- Prophet Muhammad

- Queer Jihad

- Radical Muslim

- Raed in the Middle

- RAMBLING MONOLOGUES

- Rendering Islam

- Renegade Masjid

- Rooznegar, Sina Motallebi’s WebGard

- Sabbah’s Blog

- Salam Pax – The Baghdad Blog

- Saracen.nu

- Scarlet Thisbe

- Searching for Truth in a World of Mirrors

- Seeing the Dawn

- Seeker’s Digest

- Seekersdigest.org

- shut up you fat whiner!

- Simply Islam

- Sister Scorpion

- Sister Soljah

- Sister Surviving

- Slow Motion in Style

- Sunni Sister: Blahg Blahg Blahg

- Suzzy’s id is breaking loose…

- tell me a secret

- The Arab Street Files

- The Beirut Spring

- The Islamic Feminista

- The Land of Sad Oranges

- The Muslim Contrarian

- The Muslim Postcolonial

- The Progressive Muslims Union North America Debate

- The Rosetta Stone

- The Traceless Warrior

- The Wayfarer

- TheDesertTimes

- think halal: the muslim group weblog

- Thoughts & Readings

- Through Muslim Eyes

- Turkish Torque

- Uncertainty:Iman and Farid’s Iranian weblog

- UNMEDIA: principled pragmatism

- UNN – Usayd Network News

- Uzer.Aurjee?

- Various blogs by Muslims in the West. – Google Co-op

- washed away memories…

- Welcome to MythandCulture.com and to daily Arrows – Mythologist, Maggie Macary’s blog

- word gets around

- Writeous Sister

- Writersblot Home Page

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- www.Mas’ud’s blog

- \’Aqoul

- ~*choco-bean*~

General Islam Sites

- :: Islam Channel :: – Welcome to IslamChannel Official Website

- Ad3iyah(smeekbeden)

- Al-maktoum Islamic Centre Rotterdam

- Assalamoe Aleikoem Warhmatoe Allahi Wa Barakatuhoe.

- BouG.tk

- Dades Islam en Youngsterdam

- Haq Islam – One stop portal for Islam on the web!

- Hight School Teacher Muhammad al-Harbi\’s Case

- Ibn Taymiyah Pages

- Iskandri

- Islam

- Islam Always Tomorrow Yesterday Today

- Islam denounces terrorism.com

- Islam Home

- islam-internet.nl

- Islamic Artists Society

- Leicester~Muslims

- Mere Islam

- MuslimSpace.com | MuslimSpace.com, The Premiere Muslim Portal

- Safra Project

- Saleel.com

- Sparkly Water

- Statements Against Terror

- Understand Islam

- Welcome to Imaan UK website

Islamic Scholars

Social Sciences Scholars

- ‘ilm al-insaan: Talking About the Talk

- :: .. :: zerzaust :: .. ::

- After Sept. 11: Perspectives from the Social Sciences

- Andrea Ben Lassoued

- Anth 310 – Islam in the Modern World (Spring 2002)

- anthro:politico

- AnthroBase – Social and Cultural Anthropology – A searchable database of anthropological texts

- AnthroBlogs

- AnthroBoundaries

- Anthropologist Community

- anthropology blogs

- antropologi.info – Social and Cultural Anthropology in the News

- Arabist Jansen

- Between Secularization and Religionization Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

- Bin Gregory Productions

- Blog van het Blaise Pascal Instituut

- Boas Blog

- Causes of Conflict – Thoughts on Religion, Identity and the Middle East (David Hume)

- Cicilie among the Parisians

- Cognitive Anthropology

- Comunidade Imaginada

- Cosmic Variance

- Critical Muslims

- danah boyd

- Deep Thought

- Dienekes’ Anthropology Blog

- Digital Islam

- Erkan\’s field diary

- Ethno::log

- Evamaria\’s ramblings –

- Evan F. Kohlmann – International Terrorism Consultant

- Experimental Philosophy

- For the record

- Forum Fridinum [Religionresearch.org]

- Fragments weblog

- From an Anthropological Perspective

- Gregory Bateson

- Islam & Muslims in Europe *)

- Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic, Religion

- Islam, Muslims, and an Anthropologist

- Jeremy’s Weblog

- JourneyWoman

- Juan Cole – ‘Documents on Terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’

- Keywords

- Kijken naar de pers

- languagehat.com

- Left2Right

- Leiter Reports

- Levinas and multicultural society

- Links on Islam and Muslims

- log.squig.org

- Making Anthropology Public

- Martijn de Koning Research Pages / Onderzoekspaginas

- Material World

- MensenStreken

- Modern Mass Media, Religion and the Imagination of Communities

- Moroccan Politics and Perspectives

- Multicultural Netherlands

- My blog’s in Cambridge, but my heart is in Accra

- National Study of Youth and Religion

- Natures/Cultures

- Nomadic Thoughts

- On the Human

- Philip Greenspun’s Weblog:

- Photoethnography.com home page – a resource for photoethnographers

- Qahwa Sada

- RACIAL REALITY BLOG

- Religion Gateway – Academic Info

- Religion News Blog

- Religion Newswriters Association

- Religion Research

- rikcoolsaet.be – Rik Coolsaet – Homepage

- Rites [Religionresearch.org]

- Savage Minds: Notes and Queries in Anthropology – A Group Blog

- Somatosphere

- Space and Culture

- Strange Doctrines

- TayoBlog

- Teaching Anthropology

- The Angry Anthropologist

- The Gadflyer

- The Immanent Frame | Secularism, religion and the public sphere

- The Onion

- The Panda\’s Thumb

- TheAnthroGeek

- This Blog Sits at the

- This Blog Sits at the intersection of Anthropology & Economics

- verbal privilege

- Virtually Islamic: Research and News about Islam in the Digital Age

- Wanna be an Anthropologist

- Welcome to Framing Muslims – International Research Network

- Yahya Birt

Women's Blogs / Sites

- * DURRA * Danielle Durst Britt

- -Fear Allah as He should be Feared-

- a literary silhouette

- a literary silhouette

- A Thought in the Kingdom of Lunacy

- AlMaas – Diamant

- altmuslimah.com – exploring both sides of the gender divide

- Assalaam oe allaikoum Nour al Islam

- Atralnada (Morning Dew)

- ayla\’s perspective shifts

- Beautiful Amygdala

- bouchra

- Boulevard of Broken Dreams

- Chadia17

- Claiming Equal Citizenship

- Dervish

- Fantasy web-log – web-log.nl

- Farah\’s Sowaleef

- Green Tea

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Hilsen Fra …

- Islamucation

- kaleidomuslima: fragments of my life

- Laila Lalami

- Marhaban.web-log.nl – web-log.nl

- Moslima_Y – web-log.nl

- Muslim-Refusenik The official website of Irshad Manji

- Myrtus

- Noor al-Islaam – web-log.nl

- Oh You Who Believe…

- Raising Yousuf: a diary of a mother under occupation

- SAFspace

- Salika Sufisticate

- Saloua.nl

- Saudi Eve

- SOUL, HEART, MIND, AND BODY…

- Spirit21 – Shelina Zahra Janmohamed

- Sweep the Sunshine | the mundane is the edge of glory

- Taslima Nasrin

- The Color of Rain

- The Muslimah

- Thoughts Of A Traveller

- Volkskrant Weblog — Islam, een goed geloof

- Weblog Raja Felgata | Koffie Verkeerd – The Battle | punt.nl: Je eigen gratis weblog, gratis fotoalbum, webmail, startpagina enz

- Weblog Raja Felgata | WRF

- Writing is Busy Idleness

- www.moslima.web-log.nl

- Zeitgeistgirl

- Zusters in Islam

- ~:: MARYAM ::~ Tasawwuf Blog

Ritueel en religieuze beleving Nederland

- – Alfeth.com – NL

- :: Al Basair ::

- Abu Marwan Media Publikaties

- Ahlalbait Jongeren

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Al-Amien… De Betrouwbare – Home

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Wasatiyyah.com – Home

- Anwaar al-Islaam

- anwaaralislaam.tk

- Aqiedah’s Weblog

- Arabische Lessen – Home

- Arabische Lessen – Home

- Arrayaan.net

- At-taqwa.nl

- Begrijp Islam

- Bismillaah – deboodschap.com

- Citaten van de Salaf

- Dar al-Tarjama WebSite

- Dawah-online.com

- de koraan

- de koraan

- De Koran . net – Het Islaamitische Fundament op het Net – Home

- De Leidraad, een leidraad voor je leven

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Faadi Community

- Ghimaar

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Ibn al-Qayyim

- IMAM-MALIK-Alles over Islam

- IQRA ROOM – Koran studie groep

- Islaam voor iedereen

- Islaam voor iedereen

- Islaam: Terugkeer naar het Boek (Qor-aan) en de Soennah volgens het begrip van de Vrome Voorgangers… – Home

- Islaam: Terugkeer naar het Boek (Qor-aan) en de Soennah volgens het begrip van de Vrome Voorgangers… – Home

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- islam :: messageboard

- Islam City NL, Islam en meer

- Islam, een religie

- Islamia.nl – Islamic Shop – Islamitische Winkel

- Islamitische kleding

- Islamitische kleding

- Islamitische smeekbedes

- islamtoday

- islamvoorjou – Informatie over Islam, Koran en Soenah

- kebdani.tk

- KoranOnline.NL

- Lees de Koran – Een Openbaring voor de Mensheid

- Lifemakers NL

- Marocstart.nl | Islam & Koran Startpagina

- Miesbahoel Islam Zwolle

- Mocrodream Forums

- Moslims in Almere

- Moslims online jong en vernieuwend

- Nihedmoslima

- Oprecht – Poort tot de kennis

- Quraan.nl :: quran koran kuran koeran quran-voice alquran :: Luister online naar de Quraan

- Quraan.nl online quraan recitaties :: Koran quran islam allah mohammed god al-islam moslim

- Selefie Nederland

- Stichting Al Hoeda Wa Noer

- Stichting Al Islah

- StION Stichting Islamitische Organisatie Nederland – Ahlus Sunnat Wal Djama\’ah

- Sunni Publicaties

- Sunni.nl – Home

- Teksten van Aboe Ismaiel

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Uw Keuze

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.al-thabaat.com

- www.hijaab.com

- www.uwkeuze.net

- Youth Of Islam

- Zegswijzen van de Wijzen

- \’\’ Leid ons op het rechte pad het pad degenen aan wie Gij gunsten hebt geschonken\’\’

Muslim News

Moslims & Maatschappij

Arts & Culture

- : : SamiYusuf.com : : Copyright Awakening 2006 : :

- amir normandi, photographer – bio

- Ani – SINGING FOR THE SOUL OF ISLAM – HOME

- ARTEEAST.ORG

- AZIZ

- Enter into The Home Website Of Mecca2Medina

- Kalima Translation – Reviving Translation in the Arab world

- lemonaa.tk

- MWNF – Museum With No Frontiers – Discover Islamic Art

- Nader Sadek

Misc.

'Fundamentalism'

Islam & commerce

2

Morocco

[Online] Publications

- ACVZ :: | Preliminary Studies | About marriage: choosing a spouse and the issue of forced marriages among Maroccans, Turks and Hindostani in the Netherlands

- ACVZ :: | Voorstudies | Over het huwelijk gesproken: partnerkeuze en gedwongen huwelijken onder Marokkaanse, Turkse en Hindostaanse Nederlanders

- Kennislink – ‘Dit is geen poep wat ik praat’

- Kennislink – Nederlandse moslims

Religious Movements

- :: Al Basair ::

- :: al Haqq :: de waarheid van de Islam ::

- ::Kalamullah.Com::

- Ahloelhadieth.com

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- al-Madinah (Medina) The City of Prophecy ; Islamic University of Madinah (Medina), Life in Madinah (Medina), Saudi Arabia

- American Students in Madinah

- Aqiedah’s Weblog

- Dar al-Tarjama WebSite

- Faith Over Fear – Feiz Muhammad

- Instituut voor Opvoeding & Educatie

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- islamtoday

- Moderate Muslims Refuted

- Rise And Fall Of Salafi Movement in the US by Umar Lee

- Selefie Dawah Nederland

- Selefie Nederland

- Selefienederland

- Stichting Al Hoeda Wa Noer

- Teksten van Aboe Ismaiel

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- Youth Of Islam

Nieuw boek: ‘Salafisme. Utopische idealen in een weerbarstige praktijk’

Posted on May 9th, 2014 by martijn.

Categories: [Online] Publications, Headline, Islam in the Netherlands, Murder on theo Van Gogh and related issues, My Research, Religious and Political Radicalization, Ritual and Religious Experience, Society & Politics in the Middle East, Young Muslims.

Woensdag 14 mei verschijnt bij Uitgeverij Parthenon het boek dat ik samen met mijn collega’s van de afdeling Islamstudies van de Radboud Universiteit, Joas Wagemakers en Carmen Becker, heb geschreven: Salafisme. Utopische idealen in een weerbarstige praktijk.

Hoe ben je een goede moslim?

Wat salafisten gemeen hebben, is dat zij proberen om de profeet Mohammed en de eerste generaties moslims na hem zo nauwkeurig mogelijk te volgen. Maar hoe ben je een goede, vrome moslim? Daar zijn uiteenlopende, soms tegenstrijdige ideeën over. Bijvoorbeeld: zijn strikte kledingvoorschriften enorm belangrijk of leidt die nadruk op uiterlijkheden af van de spiritualiteit? Is geloof een persoonlijk project, dat deelname aan de samenleving niet in de weg staat, of moet je je zo afzijdig mogelijk houden? ‘Er zijn tegenwoordig zelfs salafisten die oproepen om te stemmen. Daar krijgen ze zware kritiek op van anderen, want je zo actief bemoeien met wereldlijk gezag zou een stap op weg naar het ongeloof zijn.. Het is me door ons onderzoek veel duidelijker geworden dat salafist zijn vaak een worsteling is. Tegelijkertijd maakt dat harde werken ook een belangrijk deel uit van een goede moslim zijn.

Populair na ‘9/11’

In de jaren na ‘9/11’ nam de populariteit van het salafisme wereldwijd toe. Toch is de stroming overal, behalve in Saoedi-Arabië, nog altijd een minderheid binnen de islam. In Nederland zou volgens Amsterdams onderzoek zo’n 8 tot 10 procent van de moslimbevolking , dus ongeveer 80.000 mensen, geïnteresseerd kunnen zijn in een stroming als het salafisme – ‘met zo veel slagen om de arm is dat het meest exacte cijfer dat we hebben’.

Theo van Gogh

In Nederland leidde de moord op Theo van Gogh, in 2004, tot een piek in de belangstelling. ‘Deels was dat nieuwsgierigheid, maar er zit ook wat rebels in salafisme. De publieke reacties op orthodoxe moslims waren scherp, destijds. En dan krijg je een tegenreactie: als salafisten denken te worden aangevallen op hun geloof, kunnen ze fel uit de hoek komen. De laatste jaren, hebben mijn collega’s en ik de indruk, is het aantal bezoekers bij bijeenkomsten voor salafisten behoorlijk stabiel.

Arabische Lente

Het boek besteedt ook aandacht aan de gevolgen van de Arabische Lente, die de apolitieke ideeën van veel salafisten behoorlijk op z’n kop hebben gezet. Moesten salafisten langs de kant blijven staan terwijl allerlei regimes omver geworpen werden of moesten ze toch politiek actief worden? Hoewel salafisten vaak bekend staan als rigide, zijn ze in sommige gevallen uiterst flexibel met deze nieuwe uitdaging omgegaan.

Wat moeten we ermee?

Het boek Salafisme. Utopische idealen in een weerbarstige praktijk verschijnt bij Uitgeverij Parthenon en wordt op woensdag 14 mei in Nijmegen gepresenteerd in het Soeterbeeck Programma ‘Salafisme, wat moeten we ermee?’ (lezing en discussie met onder andere Ineke Roex en Roel Meijer, onder leiding van Jan Jaap de Ruiter van de Universiteit van Tilburg).

Datum: woensdag 14 mei 2014

Tijd: van 19:30 tot 21:30

Locatie: Huize Heyendael, Geert Grooteplein-Noord 9, Nijmegen

Organisator: Soeterbeeck Programma

Voor meer informatie over het programma zie HIER. Aanmelden is noodzakelijk, dat kan HIER.

Te verkrijgen vanaf 14 mei

Bij de bekende boekhandels onder andere:

Atheneum Amsterdam

Boekhandel Roelants Nijmegen

Bol.com

Boek.be

Lees de inleiding

Nieuw boek: 'Salafisme. Utopische idealen in een weerbarstige praktijk'

Posted on May 9th, 2014 by martijn.

Categories: [Online] Publications, Headline, Islam in the Netherlands, Murder on theo Van Gogh and related issues, My Research, Religious and Political Radicalization, Ritual and Religious Experience, Society & Politics in the Middle East, Young Muslims.

Woensdag 14 mei verschijnt bij Uitgeverij Parthenon het boek dat ik samen met mijn collega’s van de afdeling Islamstudies van de Radboud Universiteit, Joas Wagemakers en Carmen Becker, heb geschreven: Salafisme. Utopische idealen in een weerbarstige praktijk.

Hoe ben je een goede moslim?

Wat salafisten gemeen hebben, is dat zij proberen om de profeet Mohammed en de eerste generaties moslims na hem zo nauwkeurig mogelijk te volgen. Maar hoe ben je een goede, vrome moslim? Daar zijn uiteenlopende, soms tegenstrijdige ideeën over. Bijvoorbeeld: zijn strikte kledingvoorschriften enorm belangrijk of leidt die nadruk op uiterlijkheden af van de spiritualiteit? Is geloof een persoonlijk project, dat deelname aan de samenleving niet in de weg staat, of moet je je zo afzijdig mogelijk houden? ‘Er zijn tegenwoordig zelfs salafisten die oproepen om te stemmen. Daar krijgen ze zware kritiek op van anderen, want je zo actief bemoeien met wereldlijk gezag zou een stap op weg naar het ongeloof zijn.. Het is me door ons onderzoek veel duidelijker geworden dat salafist zijn vaak een worsteling is. Tegelijkertijd maakt dat harde werken ook een belangrijk deel uit van een goede moslim zijn.

Populair na ‘9/11’

In de jaren na ‘9/11’ nam de populariteit van het salafisme wereldwijd toe. Toch is de stroming overal, behalve in Saoedi-Arabië, nog altijd een minderheid binnen de islam. In Nederland zou volgens Amsterdams onderzoek zo’n 8 tot 10 procent van de moslimbevolking , dus ongeveer 80.000 mensen, geïnteresseerd kunnen zijn in een stroming als het salafisme – ‘met zo veel slagen om de arm is dat het meest exacte cijfer dat we hebben’.

Theo van Gogh

In Nederland leidde de moord op Theo van Gogh, in 2004, tot een piek in de belangstelling. ‘Deels was dat nieuwsgierigheid, maar er zit ook wat rebels in salafisme. De publieke reacties op orthodoxe moslims waren scherp, destijds. En dan krijg je een tegenreactie: als salafisten denken te worden aangevallen op hun geloof, kunnen ze fel uit de hoek komen. De laatste jaren, hebben mijn collega’s en ik de indruk, is het aantal bezoekers bij bijeenkomsten voor salafisten behoorlijk stabiel.

Arabische Lente

Het boek besteedt ook aandacht aan de gevolgen van de Arabische Lente, die de apolitieke ideeën van veel salafisten behoorlijk op z’n kop hebben gezet. Moesten salafisten langs de kant blijven staan terwijl allerlei regimes omver geworpen werden of moesten ze toch politiek actief worden? Hoewel salafisten vaak bekend staan als rigide, zijn ze in sommige gevallen uiterst flexibel met deze nieuwe uitdaging omgegaan.

Wat moeten we ermee?

Het boek Salafisme. Utopische idealen in een weerbarstige praktijk verschijnt bij Uitgeverij Parthenon en wordt op woensdag 14 mei in Nijmegen gepresenteerd in het Soeterbeeck Programma ‘Salafisme, wat moeten we ermee?’ (lezing en discussie met onder andere Ineke Roex en Roel Meijer, onder leiding van Jan Jaap de Ruiter van de Universiteit van Tilburg).

Datum: woensdag 14 mei 2014

Tijd: van 19:30 tot 21:30

Locatie: Huize Heyendael, Geert Grooteplein-Noord 9, Nijmegen

Organisator: Soeterbeeck Programma

Voor meer informatie over het programma zie HIER. Aanmelden is noodzakelijk, dat kan HIER.

Te verkrijgen vanaf 14 mei

Bij de bekende boekhandels onder andere:

Atheneum Amsterdam

Boekhandel Roelants Nijmegen

Bol.com

Boek.be

Lees de inleiding

Muslims of France: Colonials, Immigrants and Citizens

Posted on January 6th, 2014 by martijn.

Categories: Islam in European History, islamophobia, Multiculti Issues, Public Islam, Religious and Political Radicalization, Young Muslims.

Al Jazeera has a very interesting series on Muslims in France by filmmaker Karim Miské. They ask:

Today, there are an estimated five million Muslims living in France. A century ago, they were referred to as “colonials”. During the 1960s, they were known as “immigrants”. Today, they are “citizens”. But how have the challenges facing each generation of immigrants changed?

The first part of the series tells the story of the 5,000 Muslims who by 1904 were working on the shop floors of Paris, in the soap factories of Marseilles and in the coalfields of the north; of the Muslim soldiers who fought and died for France during the First World War; and the Muslim members of the resistance who helped liberate Paris in 1944. Born as North Africans, many would die for France. But how much did post-war France care about their sacrifices?

The second part of the series explores post-Second World War immigration and reveals a generation of Muslims who, far from expecting to one day return home, began building their lives and communities in France.

The third and final part of the series tells the stories of the young Muslims who grew up in France and entered adulthood at a time of economic crisis, massive unemployment and rampant social problems.

The series is very useful I think for teaching purposes. I will consider using it next year.

All info on the episodes taken from the Al Jazeera site

Somewhere – #Mipsterz all over the place

Posted on December 11th, 2013 by martijn.

Categories: Activism, Gender, Kinship & Marriage Issues, Public Islam, Young Muslims, Youth culture (as a practice).

In the video Somewhere in America, a bunch of young Muslim women take over the urban landscape with their skateboards, high heels, hijabs and other fashionable clothing with a Jay-Z soundtrack. The video is directed together with Sara Aghaganian and Layla and released by Abbas Rattani and Habib Yazdi of Sheikh & Bake Productions: A music video that captures the attitude “I’m dope as hell and I don’t give a @!#$%&.”. Their facebook page describes them as:

A Mipster is someone who seeks inspiration from the Islamic tradition of divine scriptures, volumes of knowledge, mystical poets, bold prophets, inspirational politicians, esoteric Imams, and our fellow human beings searching for transcendental states of consciousness. A Mipster is an ironic identity, one that serves more as a perpetual critique of oneself and of society.

The video you see here is a clean version of the Jay Z song since several people complained about the N-word that was part of the original song.

Reactions

The video has gone viral on Facebook, Buzzfeed, Jezebel, Glamour, Huffington Post. The video has triggered an interesting debate about what it means to be a young, American, Muslims, woman. Take for example dr. Suad Abdul Khabeer:

“All I know to be is a solider, for my culture” | Somewhere in America? Somewhere in America there…

Everywhere in America, a Muslim woman’s headscarf is not only some sex, swag and consumption, it also belief and beauty, defiance and struggle, secrets and shame.

I know some people are celebrating this video and others criticizing it. I think it’s pretty clear I fall in the second camp. Yet, while it could be so much more. It actually does what it intends to do so effectively. Nothing in this video should surprise you. After all it is being championed by a group called the mipsterz—as in Muslim Hipsters—with no sense of irony. A friend remarked to me that the video was particularly tragic because our champion Ibtihaj Muhammad is in it, and she has been lauded by folks like Hilary Clinton for being a role model. And this video and its background song, replete with profanity including the N-word, seem far from that acclaim. Yet I don’t think it’s incongrous that the same person who Clinton lauded would end up in a video with Jay-Z as a back drop, both Clinton and Jay assert and epitomize American Exceptionalist Capitalism par excellence—and by this I mean the way they would approrpirate her not necessarily how she sees herself. And lest we forget, even Obama has Jay on his Ipod. The video is full frontal consumption and thus can only offer narrow visions of who Muslim women are, even in the attempt to show diversity but again how American is that?! I must admit I may have been a tad bit surprised that they didn’t bleep out at least the N-word but maybe they were aiming for that “ironic” hispter racism. Maybe in the remix they will swap out Nigga for Abeed.

Also a critical comment by Sana Saeed from The Islamic Monthly:

Somewhere in America, Muslim Women Are “Cool”

The video, produced/created/directed primarily by Muslim men (oh hey voyeuristic-cinematography-through-the-Male-Gaze heyyy), doesn’t achieve anything to really fight against stereotypes: it is literally young Muslim women with awesome fashion sense against the awkward backdrop of Jay Z singing about Miley Cyrus twerking. The only semblance of purpose seems to come in with the images of Ibtihaj Muhammad who is shown in her element, doing what she does as a professional athlete. Those images are powerful and beautiful in what they are saying. Other than that, however, all we as the audience are afforded are images that, simply put, objectify the Muslim female form by denigrating it completely to the physical. Muhammad’s form as a unique Muslim woman is complemented by her matter – the stuff that makes her her; makes her Ibtihaj. As the credits below the video mention, the rest of the women (Muhammad is included in this) are merely “models” even though every single one of them has a central and important function and contribution to her respective community and in her field. Instead of showing what makes each and every one of those women Herself, they’re made into this superfluous conformity of an image we, as the audience, consume and ogle at because hey, they’re part of the aesthetic of the video. Ibtihaj is shown as a professional badass and the rest are shown as professional hot women who skate in heels and take selfies on the roof. There’s nothing wrong with the latter, in and of itself, but what a strange dissonance and incongruence in imagery?

And if that isn’t textbook objectification then I think I’ve been raging against the wrong machine since I was 14.

One of the participants in the video, Aminah Sheikh, defends her choice of participating in the video:

Why I Participated in the ‘Somewhere in America’ #Mipsterz Video

My problem with all the critiques I am reading is that you are taking away my agency and power. I made this choice, and the video is in fact a reflection of me and many Muslim women. You may not like it, and that is ok. It may not represent you, and that is even better. You probably don’t know anyone like us – even more so better!

[…]

Hijabis are humans, and that was the point of the video. I know hijabis who ride bikes, skateboard and listen to rap. You can be in denial and reinforce the ‘us and them’ dichotomies and Occidentalism. But, I personally see this as reactionary Islamist politics — this naming, shunning and shaming. It is counterproductive and not useful. Islam is a global religion with about two billion adherents and colorful, historical trajectories.

Islamic culture has not come in a vacuum. Islam is linked to a myriad of people, histories, nations and ethnicities.

The most amusing part of this post-video conversation is the class/or Marxian critique and the linking of the video to materialism and consumption. First, of all the women in the video, not one is endorsing any particular brand. Second, it certainly ironic when the majority of “Western” Muslims are living in their fancy suburban homes, driving a luxury car, jet setting through Dubai and staying in luxury hotels on their Hajj– now they want to bring class politics into the discussion.

Let’s not even get started on the race politics: I am a first generation Muslim woman living in Toronto, Canada. I have been called a terrorist post-911 more times than I can count. I am brown-skinned and by no means the normative standard of beauty. I am a daughter of parents forcefully moved during partition in India/Pakistan. Like me, none of the women in the video fit into mainstream culture. It was great giving us some representation in alternative media forms. I can only hope one day there are more Muslim women in the media when I have my own daughter.

Finally, don’t say what my identity is. I can do that for myself. Don’t take away another woman’s power or agency.

I am Canadian. I am Western. I am them, and they are me. I am definitely the same. I can be a hipster, I can be a mipster, and I can be mainstream. Oh. and yes — I listen to Jay Z.Peace out.

Another participant, Noor Tagouri expressed on Facebook that she wasn’t aware of how the final product would be:

When I was first asked to be a part of this project, I was told it was for an official music video of Yuna’s song “Loud Noises.” An inspiring song on friendship and love.

I was never told the music video fell through, and in turn a video was still going to come out of the footage shot and be set to Jay-Z’s “Somewhere in America.” I’ll admit, I was uneasy about it at first, still a bit meh about it because the explicit version was used and besides the theme of being “somewhere in America,” it wasn’t relevant to friendship, love or empowerment.

Nevertheless, the video was edited and posted before I could say anything about the drastic song change…and it remained fun/catchy. I enjoyed seeing the cool senses of fashion and recognizing faces of people who I admire. I get it. This song isn’t exactly appropriate, and I do believe the song choice is the main reason many people were thrown off about it. If it’s the way girls are dressed in their hijab, then, you really need to just accept the fact that hijab is a personal choice and everyone interprets it differently. Would it have been better to see an even MORE array of hijabis? Probably. But the video came out and though there was/is much criticism, there is also a lot of good feedback, esp from people who viewed hijab as “oppressive” and disempowering. So, I’ve decided to take the positive from this video and leave the negative. And next time, be sure that if I participate in something like this, I get the chance to see the progress before the final product is put out.

At one point the debate got (over?)heated and one of the things that happens with videos that go viral is that they are completely pulled out of their original context. As Rabia Chaudry explains:

Somewhere on the Internet, Muslim Women are being Shamed

I am really sorry that you vivacious, happy, dynamic, stylish, and I’m sure very bright young women are being brutally examined and analyzed with laser-like tenacity, and about as much empathy. It stinks to high heaven that you are being accused of promoting racism (poor song choice, but I know it had little to do with you), elitism, classism, fat shaming, immodesty, and essentially the downfall of our entire Ummah. Yes, I know. I didn’t see it coming either.

Debating the video

The next video shows the debate on Al Jazeera’s The Stream between Hajer Naili, Sana Saeed, Keziah Ridgeway and Linda Sarsour:

Earlier also a debate at HuffPo with Abbas Rattani, Hajer Naili, Sohaib Sultan, and Sana Saeed

In this debate Abbas Rattani refers to an all male mipster video, that has caused much less controversy and has only a little over 4200 views on youtube. That is this one

Dilemmas

It appears that we are much more concerned with women’s lives, bodies and dress then with men. The message of the video may be not that clear but that is probably stimulating the discussion as it leaves room for everyone to project their own meaning onto the video and onto the women in it as well. There have been a lot of comments stating that these women do not deserve to wear the hijab since they do not behave modestly. I have seen such comments (often ad hominem) from Muslims and non-Muslims signifying the attempts to control women’s bodies, attire and behaviour.

The fact that the performance in the video mixes and blurs the boundaries between pop culture, Islamic religiosity and identity and womanhood is probably also an important impetus for the debate. For some people pop culture is everything that is unislamic or even anti-Islamic. Mixing it with Islam is than often a source of controversy as it is regarded as vulgar and dangerous. At the same time for those people who want to make a strong statement in the sense of ‘Here I am, I’m not going away, deal with it’ pushing the boundaries through pop culture is often a strong tool for challenging the status quo (see also Imran Ali Malik‘s comments).

In that sense this is an important debate that goes beyond the video itself, or as Hind Makki explains (who has a great overview of the most important opinions and links):

Somewhere In America: My Thinksies & Some Linksies

while this discussion may seem trivial at first glance – that so many American Muslims are getting our scarves and kufis into a collective knot over a short clip that is essentially a fashion shoot set to a popular hip hop track – in reality, this public conversation points a collective finger on a very real question: what spaces are Muslim women occupying in American Islam?

The critiques also shows a fundamental dilemma for activists. Or two actually. First one if one wants to debunk stereotypes regarding a particular group it is difficult not to reproduce the same stereotype as well. By stating that Muslims are normal, want to have fun and fit in, the stereotype that they are abnormal, do not know how to have fun and do not fit is implicitly repeated. The second dilemma is that by showing the ‘normal Muslim’ in this video a particular category is included while others are excluded. Are those Muslims who do not have fun, who do not function in society, who are not strong women according to the definition of the video, not normal? This is certainly not what the video explicitly states, but by showing these women other women who do not resemble them are left out or made invisible. These dilemma’s notwithstanding (or maybe partly because of them) the video generated lots of comments and debate on what it means to be a Muslim woman and how to intervene in the debates on Islam.

Junge Salafiyya-Anhänger suchen im Internet nach dem „wahren Glauben“

Posted on August 29th, 2013 by martijn.

Categories: anthropology, Important Publications, ISIM/RU Research, Religious and Political Radicalization, Ritual and Religious Experience, Young Muslims.

Carmen Becker hat den Einfluss des Internets auf den Glauben junger niederländischer und deutscher Muslime untersucht, die der Salafiyya folgen. Das Internet bietet einen Ort der Begegnung, einen religiösen Raum und zugleich die Möglichkeit, selbst nach den Quelltexten und ihrer Bedeutung zu suchen. Das wird die traditionellen Formen religiöser Autorität verändern, vermutet Becker, die am 9. September 2013 an der Nimweger Radboud Universität promovieren wird.

Ebenso wie die Jugendlichen, um die es geht, spricht Carmen Becker nicht von Salafisten, sondern von „Muslimen, die der Salafiyya folgen“. „Anhänger der Salafiyya streben danach, sich möglichst genau am Propheten Mohammed und den ersten drei Generationen von Muslimen, den sogenannten ‚frommen Vorfahren‘, zu orientieren. ‚Salafisten‘ werden häufig mit Radikalisierung und Gewalt in Verbindung gebracht. Dass sie sehr orthodoxe, mitunter radikale Auffassungen vertreten, bedeutet jedoch nicht automatisch, dass man deshalb radikales Verhalten und Gewalt befürwortet.“

Laut dem deutschen Verfassungsschutz gibt es in Deutschland 3.800 aktive Salafiyya-Anhänger aller Altersgruppen; in den Niederlanden geht der nationale Koordinator für die Terrorismusbekämpfung von 3.000 Anhängern aus. „Das sind jedoch Schätzungen, die auf selbstformulierten Definitionen beruhen und von denen nicht immer klar ist, wie sie zustande gekommen sind.“

In ihrem Forschungsprojekt folgte Becker zwischen 2007 und 2010 zahlreichen Gesprächen und Aktivitäten in Foren sowie Chatrooms und sprach ausführlich mit 47 jungen Muslimen. Mitunter beteiligte sie sich zudem an Gesprächen im Internet, wobei sie sich immer als Forscherin zu erkennen gab.

Muslim werden – in einem Chatroom

Das Internet ist, so stellte Becker fest, für diese muslimischen Jugendlichen nicht nur ein Ort, an dem sie Informationen austauschen, sondern auch ein religiöser Raum, in dem sie ihren Glauben leben können. „Sie können dort reden, beten, Vorträge und Predigten hören, und es besteht auch die Möglichkeit, dem Islam beizutreten. Das setzt allerdings die Anwesenheit von Zeugen voraus, die feststellen, ob das Glaubensbekenntnis überzeugend vorgetragen wird. Das Internet stellt also für den Kern des Rituals keine Gefahr dar.“

Selbst auf die Suche gehen

Auf einer anderen Ebene übt das Internet ihrer Meinung nach mehr Einfluss aus: „Traditionell wird das Wissen über den wahren Glauben von einem Imam oder einer anderen Autorität in der Moschee vermittelt. Im Internet jedoch kann jeder – vor allem jetzt, da immer mehr Quelltexte in verschiedenen Sprachen digitalisiert werden, – die entsprechenden Texte selbst studieren. Das ist keine einfache Aufgabe: Es sind oft keine eindeutigen, unmissverständlichen Texte, und viele Übersetzungen aus dem Arabischen sind schlichtweg schlecht. Darüber hinaus dürfen sich die Gläubigen nicht selbst überschätzen und annehmen, sie könnten den Koran ohne weiteres auslegen. Der Einfluss anerkannter Autoritäten wie der islamischen Gelehrten ist deshalb weiterhin beträchtlich. Aber daneben begeben sich die Menschen selbst auf die Suche nach Belegen für bestimmte Aussagen in den religiösen Quellen und diskutieren Texte und Interpretationen mit anderen Gläubigen.“

Muslim sein im Westen

Die jungen Muslime aus dem Forschungsprojekt hören am liebsten sachkundigen Glaubensgenossen vor Ort zu, denen es gelingt, einen Bezug zwischen Lehre und Leben herzustellen. „Das kann ein junger Prediger oder ein populärer bekehrter Muslim sein – wichtig ist, dass sie sich in das Leben junger orthodoxer Muslime im Westen hineinversetzen können und ihre Sprache sprechen. Ihre Texte werden eifrig diskutiert, weil sie sich weniger mit der Frage beschäftigen, was der Prophet getan hat, als vielmehr damit, was der Prophet unter den gegebenen Umständen tun würde.“

Weniger strenggläubig? Anders!

Die Schlussfolgerung, dass der orthodoxe Glaube jugendlicher Salafiyya-Anhänger unter dem Einfluss des Internets „weniger streng“ wird, möchte Becker nicht ziehen. „Es ist noch zu früh, um zu sagen, welchen Einfluss das Internet letztendlich haben wird. Aber dass es Glaubenspraktiken verändert, davon bin ich überzeugt.“

Carmen Becker (Lindlar, Deutschland, 1977) studierte Politikwissenschaft (Schwerpunkt: Naher und Mittlerer Osten) an der Freien Universität Berlin. Ab 2004 arbeitete sie für das Auswärtige Amt in Berlin. 2007 begann sie mit der Forschung für ihre Doktorarbeit im Fachbereich Arabisch und Islam (Research Institute for Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies) der Radboud Universität. Ihr Forschungsprojekt ist Teil eines größeren Forschungsprogramms der Radboud Universität zum Thema Salafismus, wofür die Nimweger Universität 2007 Fördermittel der Niederländischen Organisation für Wissenschaftliche Forschung (NWO) erhielt.

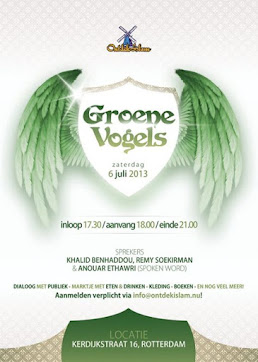

OntdekIslam Conferentie – Groene Vogels

Posted on June 25th, 2013 by martijn.

Categories: Activism, ISIM/RU Research, Notes from the Field, Religious and Political Radicalization, Society & Politics in the Middle East, Young Muslims.

Naar aanleiding van het voortdurende conflict in Syrië en de berichten van moslimjongeren die afreizen om aldaar deel te nemen aan de gewapende strijd, heeft OntdekIslam een conferentie georganiseerd.

De titel van de conferentie verwijst naar het idee dat de zielen van martelaren in de strijd worden gedragen in de harten van groene vogels die hen naar het paradijs brengen. Volgens een Hadith Qudsi zou God over deze martelaren hebben gezegd: “Hun zielen bevinden zich in groene vogels, die lantaarns hebben hangen aan de Troon, zij vliegen vrij door het Paradijs, waar zij maar willen, en dan zoeken zij beschutting in deze lantaarns”.

In de conferentie komen vragen aan bod als:

Wat is nu de exacte wijze waarop de islamitische wet- en regelgeving zich verhoudt tot de keuzes van enkele moslimjongeren om te strijden in Syrië? En is het aan de mens om een ander tot martelaar te betitelen, of behoort dit oordeel toe aan Allah swt? Deze en andere vraagstellingen worden besproken in bijdragen door broeder Khalid Benhaddou en imam Remy Soekirman. Broeder Anouar Ethawri zal middels spoken word een bijdrage leveren en ook zal er ruimte zijn voor interactie met het publiek.

Datum: Zaterdag 6 juli 2013

Adres: Centrum de Middenweg, Kerdijkstraat 16 Rotterdam.

Tijdstip: 17.30 inloop, aanvang 18.00 uur, einde 21.00 uur.

Geplaatst op verzoek van de organisatie

The Dutch 'Moroccans' Debate

Posted on January 26th, 2013 by martijn.

Categories: Multiculti Issues, Young Muslims.

The Dutch debates on integration have reached a new landmark moment: within a few weeks Dutch parliament will discuss the so-called ‘Moroccans Problem’. This term came about after a recent tragedy in the city of Almere (near Amsterdam) whereby several teenaged soccer players beat and kicked a volunteer linesman after a dispute that is not entirely clear yet. The man died the next day. At first reluctantly but after a few opinion articles in newspapers that followed the huge outcry on the internet the assailants were quickly called: ‘Moroccans’. This refers to the ethnic background of at least two young boys. Calling something by its name (benoemen), is used here as a rationale for identifying the problems (needed to tackle them) and to criticize multiculturalists who want to deny the problems. Of course, in dealing with societal issues some form of labelling of people seems inevitable, but at the same time the concepts used to classify people are not neutral or factual but implicitly take a position that often reflects a dominant discourse and a political agenda.

Nationalism & Neo-Liberalism

The Euro-crisis may appear to have taken the top of the political agenda during the last elections, at the expense of integration / Islam but that was only at a superficial level. In reality neoliberalism met nationalism during the last election campaigns: it is quite remarkable how quickly particular stereotypes on southern Europe, in particular Greece, emerged after the news broke of their financial problems: unreliable, lazy, corrupt, you name it. The EU was blamed by politicians for most of the problems (conveniently shying away from the fact that national politicians make the EU) and parties such as the Freedom Party linked the EU with the problem of the so-called mass-migration. It was supposedly the EU who caused huge waves of migrants coming to the Netherlands (in fact the idea of mass-migration has been debunked by several experts) in particular the East-Europeans and the Muslims. It is in particular Wilders who has weaved together a strong anti-EU stand with anti-immigration and anti-austerity measures. Interestingly, and disturbingly, he is severely criticized on all these points but not so much on the connections he makes between the three themes.

Other parties however see culture (used for referring to migrants) also as problematic in their election campaigns and programmes. If the migrants are presented as beneficial at all (two parties; very few sentences) it is always in relation with something like ‘but there are problems as well’. Concrete measures are proposed that always restrict migrants in order to become compatible with ‘Dutch society’ or the punish them more than other citizens (for instance in the cases of domestic and other forms of family violence). And everything that remotely resembles multiculturalism should not be subsidized anymore. There are some differences between the parties with regard to issues such as dual citizenship, the ban on face-veiling, and some other discriminatory measures of the last government.

All parties do give some attention to the struggle against racism, homophobia and discrimination but often only in general slogans. In short a homogenized picture of the Dutch society is created in which the problems are caused by outsiders (unauthorized migrants, ‘Moroccans’, Muslims) while the problems among particular categories of migrants are denied, reduced to individual responsibility or othered through the discourse of culture. As Jolle Demmers and Sameer S. Mehendale argues the ‘faces of immigrants have served as ideal, identifiable flash points for new repertoires of belonging and othering’ in a neoliberal, ‘atomized’ society endulging in ‘fantasies of purity and the moralization of culture and citizenship’.

The Discourse of Moroccan Street Terrorists

In particular second generation Moroccan-Dutch youth have a bad reputation for causing trouble in the streets, being rude and insulting to women and for scoring high in many statistics on crime, unemployment and problems in education. Using the label ‘Moroccan’ only makes sense because of the dominant culture talk: Moroccan-Dutch youth cause problems, or more, they are a problem because of their culture which is perceived as macho and mysoginist, anti-western and violent. Much of the debate after the death of the referee was therefore about the relation between culture and crime. A flawed question because firstly it is based upon a homogenized and essentialist concept of culture that has no analytical value, and secondly although culture (in a non-essentalist version) always plays a role in crime it is impossible to determine a causal relation between culture and crime. Thirdly (and related to the former) because culture in the essentialized version is a ‘group-concept’ that has little value in explaining the behaviour of an individual.

In most of these accounts the underlying assumption is that Moroccan-Dutch youth should be educated into the ‘Dutch’ rules of conduct and the core values of Dutch society (in the idealized version being secular and upholding sexual freedoms) and in particular their parents should ‘shape up’ and ‘take responsibility’ for the actions of their children. That this type of analysis and its related ‘solution’ is part of the issue by (re-)producing Moroccan-Dutch as people out of place is entirely obscured. Dutch society has left the somewhat pacifying model of the 1990s with regard to the integration of migrants for a more confrontational model after 2000. This has however not resulted in closing the gap with regard to socio-economic inequality and neither with regard to convivial contacts. A recent report by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) found that social contact between white native Dutch and the main immigrant groups (Moroccan-Dutch, Turkish-Dutch, Antillean-Dutch and Surinamese-Dutch) has actually decreased over the past 17 years. Half a century after the first Turkish and Moroccan guest workers arrived in the Netherlands, only 28% of Turkish-Dutch and 37% of Moroccan-Dutch identify themselves strongly as Dutch. And while their Dutch language skills have improved, immigrant groups felt less accepted in Dutch society in 2011 than in 2002. This however does not lead to the conclusion that something is wrong with the current model of integration (with its focus on cultural values) but re-affirms the image that something is wrong with (the culture of) migrants.

Gender & Race

The debate is not only about culture, ethnicity and religion. It is also about gender and race. Gender in the sense that often the Moroccan-Dutch girls are seen as the symbols of upward social mobilitiy while being oppressed at the same time by Moroccan-Dutch / Muslim men. Furthermore the boys figure as the poster boy for what is wrong with multiculturalism, Islam and ‘Moroccan culture’ and in need of government intervention and being taught the appropriate model of masculinity in a secular liberal society. This is in particular clear after a Moroccan-Dutch woman stabbed and killed her daughter. This led immediately to the conclusion that we have a possible honour killing at hand here; again the focus on culture whilst calls for closer police monitoring.

Race is the other theme here. Although the Dutch discourse is not so much about race as it is about culture (a difference that has important consequences) there is certainly a racialization going on. First of all essentializing culture to such a degree that is seen as a causal factor in individual wrongdoings is a form of cultural determinism very close to the biological determinism that is part of some race discourse. Secondly, the body is an important marker of otherness. Recently a Turkish-Dutch young man requested a name change because with his ‘Turkish-sounding’ first name he was ‘mistaken’ to be a ‘foreigner’ and a ‘Muslim’ as he was ‘Dutch’ (the young man had an Turkish-Dutch father and ethnic Dutch mother). Moreover the newspaper described him as ‘looking Dutch‘. I don’t know how the young man actually looks like, but I think we can assume here the young man looks ‘white’. The reference here to ‘Turkish’ and ‘Muslim’ shows that skin, eyes and hair color are not (only) signifiers of the exotic other anymore but, through the intersection with ethnicity and Islam, have also come to embody the threatening other in the today’s political and every day imagination.

The Moroccans Debate as Flash Potential

The latter is of course also strongly related to Islam as a threat and apparently minor issues can still explode the Dutch debates for example a Dutch amusement park announcing to establish a Muslim prayer room and the controversy surrounding the ‘halal-homes’ in Amsterdam whereby a social-housing corporation reconstructed houses with partitions separating men and women. The fact that the term ‘halal-homes’ was an invention by a local newspaper, that the houses were fit for non-Muslims as well (actually enjoying it there and living there in larger numbers than before) was lost. The first example shows how the fear of Islamization partly comes about when arrangements for Muslims are made in particular areas that are connected to people’s daily lives, the second example shows how far this fear goes; it does not only come about in relation to public manifestations of Islam but even in relation to Muslims’ private living arrangements. It shows furthermore how superficial the perceived peace on integration issues actually is. Not only horrible events lead to outbursts but also relatively minor issues. This gives these issues a certain ‘flash potential of identity politics’ as explained by Hagendoorn and Sniderman: the speed with which large numbers can be mobilized in opposition to multiculturalism and that serves as an excellent repertoire for politicians to make use of and and to keep the image of the ideal moral community where things like these ‘just not happen’ intact.

The culture talk in integration masks the ways different modes of exclusion and makes it actually harder to pin down: ‘we are not excluding people, we work very hard to integrate them’. The problems with Moroccan-Dutch are then not problems of a society lacking social cohesion, or of a social category at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchies or problems of families that to some extend are disintegrated, but problems of ‘Moroccan culture’ that appears to be just impossible (or reifying it: unwilling) to assimilate.

Paradox of resistance

All of this leads to a problematic paradox for migrants. The understandable emotions over the death of a referee are channelled through defining a particular social category, Moroccan-Dutch, as a problem: ‘Moroccan’. Being defined as a problem is problematic for people and resistance among Moroccan-Dutch people against such labelling (for example by saying, no not all Moroccans are like this, or yes there are problems but look at how well some of us do) is bringing about the accusation of having a victim mentality. Something that does not belong to a liberal society where people take responsibility for their actions.

At the same time individual Moroccan-Dutch are turned into representatives of ‘their own group’ through the label ‘Moroccan’ and they are held accountable for the actions of others. Protest against the exclusion that occurs by being labelled as a problem therefore leads to the accusation of (still) not being integrated enough and ‘not willing or able to face the facts’. Events such as the death of the referee than brings about the question ‘What more do we need to do for/with them’? Here the public statements (or myths) of the Netherlands as a freedom loving, tolerant country turn into racist and intolerant forms of politics while the individual experiences among Moroccan-Dutch of being excluded are re-affirmed, discarded and to a certain extent made invisible through the discourse of integration.

The Dutch ‘Moroccans’ Debate

Posted on January 26th, 2013 by martijn.

Categories: Multiculti Issues, Young Muslims.

The Dutch debates on integration have reached a new landmark moment: within a few weeks Dutch parliament will discuss the so-called ‘Moroccans Problem’. This term came about after a recent tragedy in the city of Almere (near Amsterdam) whereby several teenaged soccer players beat and kicked a volunteer linesman after a dispute that is not entirely clear yet. The man died the next day. At first reluctantly but after a few opinion articles in newspapers that followed the huge outcry on the internet the assailants were quickly called: ‘Moroccans’. This refers to the ethnic background of at least two young boys. Calling something by its name (benoemen), is used here as a rationale for identifying the problems (needed to tackle them) and to criticize multiculturalists who want to deny the problems. Of course, in dealing with societal issues some form of labelling of people seems inevitable, but at the same time the concepts used to classify people are not neutral or factual but implicitly take a position that often reflects a dominant discourse and a political agenda.

Nationalism & Neo-Liberalism

The Euro-crisis may appear to have taken the top of the political agenda during the last elections, at the expense of integration / Islam but that was only at a superficial level. In reality neoliberalism met nationalism during the last election campaigns: it is quite remarkable how quickly particular stereotypes on southern Europe, in particular Greece, emerged after the news broke of their financial problems: unreliable, lazy, corrupt, you name it. The EU was blamed by politicians for most of the problems (conveniently shying away from the fact that national politicians make the EU) and parties such as the Freedom Party linked the EU with the problem of the so-called mass-migration. It was supposedly the EU who caused huge waves of migrants coming to the Netherlands (in fact the idea of mass-migration has been debunked by several experts) in particular the East-Europeans and the Muslims. It is in particular Wilders who has weaved together a strong anti-EU stand with anti-immigration and anti-austerity measures. Interestingly, and disturbingly, he is severely criticized on all these points but not so much on the connections he makes between the three themes.

Other parties however see culture (used for referring to migrants) also as problematic in their election campaigns and programmes. If the migrants are presented as beneficial at all (two parties; very few sentences) it is always in relation with something like ‘but there are problems as well’. Concrete measures are proposed that always restrict migrants in order to become compatible with ‘Dutch society’ or the punish them more than other citizens (for instance in the cases of domestic and other forms of family violence). And everything that remotely resembles multiculturalism should not be subsidized anymore. There are some differences between the parties with regard to issues such as dual citizenship, the ban on face-veiling, and some other discriminatory measures of the last government.

All parties do give some attention to the struggle against racism, homophobia and discrimination but often only in general slogans. In short a homogenized picture of the Dutch society is created in which the problems are caused by outsiders (unauthorized migrants, ‘Moroccans’, Muslims) while the problems among particular categories of migrants are denied, reduced to individual responsibility or othered through the discourse of culture. As Jolle Demmers and Sameer S. Mehendale argues the ‘faces of immigrants have served as ideal, identifiable flash points for new repertoires of belonging and othering’ in a neoliberal, ‘atomized’ society endulging in ‘fantasies of purity and the moralization of culture and citizenship’.

The Discourse of Moroccan Street Terrorists

In particular second generation Moroccan-Dutch youth have a bad reputation for causing trouble in the streets, being rude and insulting to women and for scoring high in many statistics on crime, unemployment and problems in education. Using the label ‘Moroccan’ only makes sense because of the dominant culture talk: Moroccan-Dutch youth cause problems, or more, they are a problem because of their culture which is perceived as macho and mysoginist, anti-western and violent. Much of the debate after the death of the referee was therefore about the relation between culture and crime. A flawed question because firstly it is based upon a homogenized and essentialist concept of culture that has no analytical value, and secondly although culture (in a non-essentalist version) always plays a role in crime it is impossible to determine a causal relation between culture and crime. Thirdly (and related to the former) because culture in the essentialized version is a ‘group-concept’ that has little value in explaining the behaviour of an individual.

In most of these accounts the underlying assumption is that Moroccan-Dutch youth should be educated into the ‘Dutch’ rules of conduct and the core values of Dutch society (in the idealized version being secular and upholding sexual freedoms) and in particular their parents should ‘shape up’ and ‘take responsibility’ for the actions of their children. That this type of analysis and its related ‘solution’ is part of the issue by (re-)producing Moroccan-Dutch as people out of place is entirely obscured. Dutch society has left the somewhat pacifying model of the 1990s with regard to the integration of migrants for a more confrontational model after 2000. This has however not resulted in closing the gap with regard to socio-economic inequality and neither with regard to convivial contacts. A recent report by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) found that social contact between white native Dutch and the main immigrant groups (Moroccan-Dutch, Turkish-Dutch, Antillean-Dutch and Surinamese-Dutch) has actually decreased over the past 17 years. Half a century after the first Turkish and Moroccan guest workers arrived in the Netherlands, only 28% of Turkish-Dutch and 37% of Moroccan-Dutch identify themselves strongly as Dutch. And while their Dutch language skills have improved, immigrant groups felt less accepted in Dutch society in 2011 than in 2002. This however does not lead to the conclusion that something is wrong with the current model of integration (with its focus on cultural values) but re-affirms the image that something is wrong with (the culture of) migrants.

Gender & Race

The debate is not only about culture, ethnicity and religion. It is also about gender and race. Gender in the sense that often the Moroccan-Dutch girls are seen as the symbols of upward social mobilitiy while being oppressed at the same time by Moroccan-Dutch / Muslim men. Furthermore the boys figure as the poster boy for what is wrong with multiculturalism, Islam and ‘Moroccan culture’ and in need of government intervention and being taught the appropriate model of masculinity in a secular liberal society. This is in particular clear after a Moroccan-Dutch woman stabbed and killed her daughter. This led immediately to the conclusion that we have a possible honour killing at hand here; again the focus on culture whilst calls for closer police monitoring.

Race is the other theme here. Although the Dutch discourse is not so much about race as it is about culture (a difference that has important consequences) there is certainly a racialization going on. First of all essentializing culture to such a degree that is seen as a causal factor in individual wrongdoings is a form of cultural determinism very close to the biological determinism that is part of some race discourse. Secondly, the body is an important marker of otherness. Recently a Turkish-Dutch young man requested a name change because with his ‘Turkish-sounding’ first name he was ‘mistaken’ to be a ‘foreigner’ and a ‘Muslim’ as he was ‘Dutch’ (the young man had an Turkish-Dutch father and ethnic Dutch mother). Moreover the newspaper described him as ‘looking Dutch‘. I don’t know how the young man actually looks like, but I think we can assume here the young man looks ‘white’. The reference here to ‘Turkish’ and ‘Muslim’ shows that skin, eyes and hair color are not (only) signifiers of the exotic other anymore but, through the intersection with ethnicity and Islam, have also come to embody the threatening other in the today’s political and every day imagination.

The Moroccans Debate as Flash Potential

The latter is of course also strongly related to Islam as a threat and apparently minor issues can still explode the Dutch debates for example a Dutch amusement park announcing to establish a Muslim prayer room and the controversy surrounding the ‘halal-homes’ in Amsterdam whereby a social-housing corporation reconstructed houses with partitions separating men and women. The fact that the term ‘halal-homes’ was an invention by a local newspaper, that the houses were fit for non-Muslims as well (actually enjoying it there and living there in larger numbers than before) was lost. The first example shows how the fear of Islamization partly comes about when arrangements for Muslims are made in particular areas that are connected to people’s daily lives, the second example shows how far this fear goes; it does not only come about in relation to public manifestations of Islam but even in relation to Muslims’ private living arrangements. It shows furthermore how superficial the perceived peace on integration issues actually is. Not only horrible events lead to outbursts but also relatively minor issues. This gives these issues a certain ‘flash potential of identity politics’ as explained by Hagendoorn and Sniderman: the speed with which large numbers can be mobilized in opposition to multiculturalism and that serves as an excellent repertoire for politicians to make use of and and to keep the image of the ideal moral community where things like these ‘just not happen’ intact.

The culture talk in integration masks the ways different modes of exclusion and makes it actually harder to pin down: ‘we are not excluding people, we work very hard to integrate them’. The problems with Moroccan-Dutch are then not problems of a society lacking social cohesion, or of a social category at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchies or problems of families that to some extend are disintegrated, but problems of ‘Moroccan culture’ that appears to be just impossible (or reifying it: unwilling) to assimilate.

Paradox of resistance

All of this leads to a problematic paradox for migrants. The understandable emotions over the death of a referee are channelled through defining a particular social category, Moroccan-Dutch, as a problem: ‘Moroccan’. Being defined as a problem is problematic for people and resistance among Moroccan-Dutch people against such labelling (for example by saying, no not all Moroccans are like this, or yes there are problems but look at how well some of us do) is bringing about the accusation of having a victim mentality. Something that does not belong to a liberal society where people take responsibility for their actions.

At the same time individual Moroccan-Dutch are turned into representatives of ‘their own group’ through the label ‘Moroccan’ and they are held accountable for the actions of others. Protest against the exclusion that occurs by being labelled as a problem therefore leads to the accusation of (still) not being integrated enough and ‘not willing or able to face the facts’. Events such as the death of the referee than brings about the question ‘What more do we need to do for/with them’? Here the public statements (or myths) of the Netherlands as a freedom loving, tolerant country turn into racist and intolerant forms of politics while the individual experiences among Moroccan-Dutch of being excluded are re-affirmed, discarded and to a certain extent made invisible through the discourse of integration.

New Book: Whatever Happened to the Islamists?

Posted on November 8th, 2012 by martijn.

Categories: Important Publications, ISIM/RU Research, Murder on theo Van Gogh and related issues, Public Islam, Religious and Political Radicalization, Ritual and Religious Experience, Society & Politics in the Middle East, Young Muslims.

At France24 we find an interview with sociologist of Islam, Amel Boubekeur.

Amel Boubekeur, Sociologist and expert on political Islam – FRANCE 24

As the West struggles to wrap its head around the repercussions of the Arab Spring, one issue that stands out is the increasing role of Islamists in all aspects of life. So how should Western leaders reframe their approach when it comes to dealing with Islamist politicians? Annette Young talks to Amel Boubekeur, a sociologist and the co-author of “Whatever Happened to the Islamists?”

Watch the interesting interview here:

Olivier Roy and Amel Boubekeur have edited a volume on Islamism and political Islam:Whatever Happened to the Islamists?

Islamism and political Islam might seem like contemporary phenomena, but the roots of both movements can be traced back more than a century. Nevertheless, the utopian beliefs of Islamism have been irrevocably changed by the processes of modernization—especially globalization—which have taken the philosophy into unmistakable new directions.