Guest authors

You are looking at posts in the category Guest authors.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Sep | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

Pages

- About

- C L O S E R moves to….C L O S E R

- Contact Me

- Interventions – Forces that Bind or Divide

- ISIM Review via Closer

- Publications

- Research

Categories

- (Upcoming) Events (33)

- [Online] Publications (26)

- Activism (117)

- anthropology (113)

- Method (13)

- Arts & culture (88)

- Asides (2)

- Blind Horses (33)

- Blogosphere (192)

- Burgerschapserie 2010 (50)

- Citizenship Carnival (5)

- Dudok (1)

- Featured (5)

- Gender, Kinship & Marriage Issues (265)

- Gouda Issues (91)

- Guest authors (58)

- Headline (76)

- Important Publications (159)

- Internal Debates (275)

- International Terrorism (437)

- ISIM Leiden (5)

- ISIM Research II (4)

- ISIM/RU Research (171)

- Islam in European History (2)

- Islam in the Netherlands (219)

- Islamnews (56)

- islamophobia (59)

- Joy Category (56)

- Marriage (1)

- Misc. News (891)

- Morocco (70)

- Multiculti Issues (749)

- Murder on theo Van Gogh and related issues (326)

- My Research (118)

- Notes from the Field (82)

- Panoptic Surveillance (4)

- Public Islam (244)

- Religion Other (109)

- Religious and Political Radicalization (635)

- Religious Movements (54)

- Research International (55)

- Research Tools (3)

- Ritual and Religious Experience (58)

- Society & Politics in the Middle East (159)

- Some personal considerations (146)

- Deep in the woods… (18)

- Stadsdebat Rotterdam (3)

- State of Science (5)

- Twitwa (5)

- Uncategorized (74)

- Young Muslims (459)

- Youth culture (as a practice) (157)

General

- ‘In the name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful’

- – Lotfi Haddi –

- …Kelaat Mgouna…….Ait Ouarchdik…

- ::–}{Nour Al-Islam}{–::

- Al-islam.nl De ware godsdienst voor Allah is de Islam

- Allah Is In The House

- Almaas

- amanullah.org

- Amr Khaled Official Website

- An Islam start page and Islamic search engine – Musalman.com

- arabesque.web-log.nl

- As-Siraat.net

- assadaaka.tk

- Assembley for the Protection of Hijab

- Authentieke Kennis

- Azaytouna – Meknes Azaytouna

- berichten over allochtonen in nederland – web-log.nl

- Bladi.net : Le Portail de la diaspora marocaine

- Bnai Avraham

- BrechtjesBlogje

- Classical Values

- De islam

- DimaDima.nl / De ware godsdienst? bij allah is de islam

- emel – the muslim lifestyle magazine

- Ethnically Incorrect

- fernaci

- Free Muslim Coalition Against Terrorism

- Frontaal Naakt. Ongesluierde opinies, interviews & achtergronden

- Hedendaagse wetenswaardigheden…

- History News Network

- Homepage Al Nisa

- hoofddoek.tk – Een hoofddoek, je goed recht?

- IMRA: International Muslima Rights Association

- Informed Comment

- Insight to Religions

- Instapundit.com

- Interesting Times

- Intro van Abdullah Biesheuvel

- islaam

- Islam Ijtihad World Politics Religion Liberal Islam Muslim Quran Islam in America

- Islam Ijtihad World Politics Religion Liberal Islam Muslim Quran Islam in America

- Islam Website: Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic, Religion

- Islamforum

- Islamic Philosophy Online

- Islamica Magazine

- islamicate

- Islamophobia Watch

- Islamsevrouw.web-log.nl

- Islamwereld-alles wat je over de Islam wil weten…

- Jihad: War, Terrorism, and Peace in Islam

- JPilot Chat Room

- Madrid11.net

- Marocstart.nl – De marokkaanse startpagina!

- Maryams.Net – Muslim Women and their Islam

- Michel

- Modern Muslima.com

- Moslimjongeren Amsterdam

- Moslimjongeren.nl

- Muslim Peace Fellowship

- Muslim WakeUp! Sex & The Umma

- Muslimah Connection

- Muslims Against Terrorism (MAT)

- Mutma’inaa

- namira

- Otowi!

- Ramadan.NL

- Religion, World Religions, Comparative Religion – Just the facts on the world\’s religions.

- Ryan

- Sahabah

- Salafi Start Siden – The Salafi Start Page

- seifoullah.tk

- Sheikh Abd al Qadir Jilani Home Page

- Sidi Ahmed Ibn Mustafa Al Alawi Radhiya Allahu T’aala ‘Anhu (Islam, tasawuf – Sufism – Soufisme)

- Stichting Vangnet

- Storiesofmalika.web-log.nl

- Support Sanity – Israel / Palestine

- Tekenen van Allah\’s Bestaan op en in ons Lichaam

- Terrorism Unveiled

- The Coffee House | TPMCafe

- The Inter Faith Network for the UK

- The Ni’ma Foundation

- The Traveller’s Souk

- The \’Hofstad\’ terrorism trial – developments

- Thoughts & Readings

- Uitgeverij Momtazah | Helmond

- Un-veiled.net || Un-veiled Reflections

- Watan.nl

- Welkom bij Islamic webservices

- Welkom bij vangnet. De site voor islamitische jongeren!

- welkom moslim en niet moslims

- Yabiladi Maroc – Portail des Marocains dans le Monde

Dutch [Muslims] Blogs

- Hedendaagse wetenswaardigheden…

- Abdelhakim.nl

- Abdellah.nl

- Abdulwadud.web-log.nl

- Abou Jabir – web-log.nl

- Abu Bakker

- Abu Marwan Media Publikaties

- Acta Academica Tijdschrift voor Islam en Dialoog

- Ahamdoellilah – web-log.nl

- Ahlu Soennah – Abou Yunus

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Al Moudjahideen

- Al-Adzaan

- Al-Islaam: Bismilaahi Rahmaani Rahiem

- Alesha

- Alfeth.com

- Anoniempje.web-log.nl

- Ansaar at-Tawheed

- At-Tibyan Nederland

- beni-said.tk

- Blog van moemina3 – Skyrock.com

- bouchra

- CyberDjihad

- DE SCHRIJVENDE MOSLIMS

- DE VROLIJKE MOSLIM ;)

- Dewereldwachtopmij.web-log.nl

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Eali.web-log.nl

- Een genade voor de werelden

- Enige wapen tegen de Waarheid is de leugen…

- ErTaN

- ewa

- Ezel & Os v2

- Gizoh.tk [.::De Site Voor Jou::.]

- Grappige, wijze verhalen van Nasreddin Hodja. Turkse humor.

- Hanifa Lillah

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Het laatste nieuws lees je als eerst op Maroc-Media

- Homow Universalizzz

- Ibn al-Qayyim

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- Islam Blog – Juli 2007

- Islam in het Nieuws – web-log.nl

- Islam, een religie

- Islam, een religie

- Islamic Sisters – web-log.nl

- Islamiway’s Weblog

- Islamtawheed’s Blog

- Jihaad

- Jihad

- Journalista

- La Hawla Wa La Quwatta Illa Billah

- M O S L I M J O N G E R E N

- M.J.Ede – Moslimjongeren Ede

- Mahdi\’s Weblog | Vrijheid en het vrije woord | punt.nl: Je eigen gratis weblog, gratis fotoalbum, webmail, startpagina enz

- Maktab.nl (Zawaj – islamitische trouwsite)

- Marocdream.nl – Home

- Marokkaanse.web-log.nl

- Marokkanen Weblog

- Master Soul

- Miboon

- Miesjelle.web-log.nl

- Mijn Schatjes

- Moaz

- moeminway – web-log.nl

- Moslima_Y – web-log.nl

- mosta3inabilaah – web-log.nl

- Muhaajir in islamitisch Zuid-Oost Azië

- Mumin al-Bayda (English)

- Mustafa786.web-log.nl

- Oprecht – Poort tot de kennis

- Said.nl

- saifullah.nl – Jihad al-Haq begint hier!

- Salaam Aleikum

- Sayfoudien – web-log.nl

- soebhanAllah

- Soerah19.web-log.nl – web-log.nl

- Steun Palestina

- Stichting Moslimanetwerk

- Stories of Malika

- supermaroc

- Ummah Nieuws – web-log.nl

- Volkskrant Weblog — Alib Bondon

- Volkskrant Weblog — Moslima Journalista

- Vraag en antwoord…

- wat is Islam

- Wat is islam?

- Weblog – a la Maroc style

- website van Jamal

- Wij Blijven Hier

- Wij Blijven Hier

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- www.moslima.web-log.nl

- Yakini Time

- Youth Of Islam

- Youth Of Islam

- [fikra]

Non-Dutch Muslims Blogs

- Lanallah __Islamic BlogZine__

- This journey ends but only with The Beginning

- ‘the middle place’

- …Never Judge a Person By His or Her Blog…

- …under the tree…

- A Comment on PMUNA

- A Dervish’s Du`a’

- A Family in Baghdad

- A Garden of Children

- A Muslim Mother’s Thoughts / Islamic Parenting

- A Struggle in Uncertainty, Such is Life

- About Afghanistan

- adnan.org: good design, bad idea

- Afiyah

- Ahmeds World of Islam

- Al Musawwir

- Al-Musharaka

- Almiraya tBLOG – O, happy the soul that saw its own faults

- Almusawwir

- an open window

- Anak Alam

- aNaRcHo AkBaR

- Anthology

- AnthroGal’s World

- Arabian Passion

- ArRihla

- Articles Blog

- Asylum Seeker

- avari-nameh

- Baghdad Burning

- Being Noor Javed

- Bismillah

- bloggin’ muslimz.. Linking Muslim bloggers around the globe

- Blogging Islamic Perspective

- Chapati Mystery

- City of Brass – Principled pragmatism at the maghrib of one age, the fajr of another

- COUNTERCOLUMN: All Your Bias Are Belong to Us

- d i z z y l i m i t s . c o m >> muslim sisters united w e b r i n g

- Dar-al-Masnavi

- Day in the life of an American Muslim Woman

- Don’t Shoot!…

- eat-halal guy

- Eye on Gay Muslims

- Eye on Gay Muslims

- Figuring it all out for nearly one quarter of a century

- Free Alaa!

- Friends, Romans, Countrymen…. lend me 5 bux!

- From Peer to Peer ~ A Weblog about P2P File & Idea Sharing and More…

- Ghost of a flea

- Ginny’s Thoughts and Things

- God, Faith, and a Pen: The Official Blog of Dr. Hesham A. Hassaballa

- Golublog

- Green Data

- gulfreporter

- Hadeeth Blog

- Hadouta

- Hello from the land of the Pharaoh

- Hello From the land of the Pharaohs Egypt

- Hijabi Madness

- Hijabified

- HijabMan’s Blog

- Ihsan-net

- Inactivity

- Indigo Jo Blogs

- Iraq Blog Count

- Islam 4 Real

- Islamiblog

- Islamicly Locked

- Izzy Mo’s Blog

- Izzy Mo’s Blog

- Jaded Soul…….Unplugged…..

- Jeneva un-Kay-jed- My Bad Behavior Sanctuary

- K-A-L-E-I-D-O-S-C-O-P-E

- Lawrence of Cyberia

- Letter From Bahrain

- Life of an American Muslim SAHM whose dh is working in Iraq

- Manal and Alaa\’s bit bucket | free speech from the bletches

- Me Vs. MysElF

- Mental Mayhem

- Mere Islam

- Mind, Body, Soul : Blog

- Mohammad Ali Abtahi Webnevesht

- MoorishGirl

- Muslim Apple

- muslim blogs

- Muslims Under Progress…

- My heart speaks

- My Little Bubble

- My Thoughts

- Myself | Hossein Derakhshan’s weblog (English)

- neurotic Iraqi wife

- NINHAJABA

- Niqaabi Forever, Insha-Allah Blog with Islamic nasheeds and lectures from traditional Islamic scholars

- Niqabified: Irrelevant

- O Muhammad!

- Otowi!

- Pak Positive – Pakistani News for the Rest of Us

- Periphery

- Pictures in Baghdad

- PM’s World

- Positive Muslim News

- Procrastination

- Prophet Muhammad

- Queer Jihad

- Radical Muslim

- Raed in the Middle

- RAMBLING MONOLOGUES

- Rendering Islam

- Renegade Masjid

- Rooznegar, Sina Motallebi’s WebGard

- Sabbah’s Blog

- Salam Pax – The Baghdad Blog

- Saracen.nu

- Scarlet Thisbe

- Searching for Truth in a World of Mirrors

- Seeing the Dawn

- Seeker’s Digest

- Seekersdigest.org

- shut up you fat whiner!

- Simply Islam

- Sister Scorpion

- Sister Soljah

- Sister Surviving

- Slow Motion in Style

- Sunni Sister: Blahg Blahg Blahg

- Suzzy’s id is breaking loose…

- tell me a secret

- The Arab Street Files

- The Beirut Spring

- The Islamic Feminista

- The Land of Sad Oranges

- The Muslim Contrarian

- The Muslim Postcolonial

- The Progressive Muslims Union North America Debate

- The Rosetta Stone

- The Traceless Warrior

- The Wayfarer

- TheDesertTimes

- think halal: the muslim group weblog

- Thoughts & Readings

- Through Muslim Eyes

- Turkish Torque

- Uncertainty:Iman and Farid’s Iranian weblog

- UNMEDIA: principled pragmatism

- UNN – Usayd Network News

- Uzer.Aurjee?

- Various blogs by Muslims in the West. – Google Co-op

- washed away memories…

- Welcome to MythandCulture.com and to daily Arrows – Mythologist, Maggie Macary’s blog

- word gets around

- Writeous Sister

- Writersblot Home Page

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- www.Mas’ud’s blog

- \’Aqoul

- ~*choco-bean*~

General Islam Sites

- :: Islam Channel :: – Welcome to IslamChannel Official Website

- Ad3iyah(smeekbeden)

- Al-maktoum Islamic Centre Rotterdam

- Assalamoe Aleikoem Warhmatoe Allahi Wa Barakatuhoe.

- BouG.tk

- Dades Islam en Youngsterdam

- Haq Islam – One stop portal for Islam on the web!

- Hight School Teacher Muhammad al-Harbi\’s Case

- Ibn Taymiyah Pages

- Iskandri

- Islam

- Islam Always Tomorrow Yesterday Today

- Islam denounces terrorism.com

- Islam Home

- islam-internet.nl

- Islamic Artists Society

- Leicester~Muslims

- Mere Islam

- MuslimSpace.com | MuslimSpace.com, The Premiere Muslim Portal

- Safra Project

- Saleel.com

- Sparkly Water

- Statements Against Terror

- Understand Islam

- Welcome to Imaan UK website

Islamic Scholars

Social Sciences Scholars

- ‘ilm al-insaan: Talking About the Talk

- :: .. :: zerzaust :: .. ::

- After Sept. 11: Perspectives from the Social Sciences

- Andrea Ben Lassoued

- Anth 310 – Islam in the Modern World (Spring 2002)

- anthro:politico

- AnthroBase – Social and Cultural Anthropology – A searchable database of anthropological texts

- AnthroBlogs

- AnthroBoundaries

- Anthropologist Community

- anthropology blogs

- antropologi.info – Social and Cultural Anthropology in the News

- Arabist Jansen

- Between Secularization and Religionization Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

- Bin Gregory Productions

- Blog van het Blaise Pascal Instituut

- Boas Blog

- Causes of Conflict – Thoughts on Religion, Identity and the Middle East (David Hume)

- Cicilie among the Parisians

- Cognitive Anthropology

- Comunidade Imaginada

- Cosmic Variance

- Critical Muslims

- danah boyd

- Deep Thought

- Dienekes’ Anthropology Blog

- Digital Islam

- Erkan\’s field diary

- Ethno::log

- Evamaria\’s ramblings –

- Evan F. Kohlmann – International Terrorism Consultant

- Experimental Philosophy

- For the record

- Forum Fridinum [Religionresearch.org]

- Fragments weblog

- From an Anthropological Perspective

- Gregory Bateson

- Islam & Muslims in Europe *)

- Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic, Religion

- Islam, Muslims, and an Anthropologist

- Jeremy’s Weblog

- JourneyWoman

- Juan Cole – ‘Documents on Terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’

- Keywords

- Kijken naar de pers

- languagehat.com

- Left2Right

- Leiter Reports

- Levinas and multicultural society

- Links on Islam and Muslims

- log.squig.org

- Making Anthropology Public

- Martijn de Koning Research Pages / Onderzoekspaginas

- Material World

- MensenStreken

- Modern Mass Media, Religion and the Imagination of Communities

- Moroccan Politics and Perspectives

- Multicultural Netherlands

- My blog’s in Cambridge, but my heart is in Accra

- National Study of Youth and Religion

- Natures/Cultures

- Nomadic Thoughts

- On the Human

- Philip Greenspun’s Weblog:

- Photoethnography.com home page – a resource for photoethnographers

- Qahwa Sada

- RACIAL REALITY BLOG

- Religion Gateway – Academic Info

- Religion News Blog

- Religion Newswriters Association

- Religion Research

- rikcoolsaet.be – Rik Coolsaet – Homepage

- Rites [Religionresearch.org]

- Savage Minds: Notes and Queries in Anthropology – A Group Blog

- Somatosphere

- Space and Culture

- Strange Doctrines

- TayoBlog

- Teaching Anthropology

- The Angry Anthropologist

- The Gadflyer

- The Immanent Frame | Secularism, religion and the public sphere

- The Onion

- The Panda\’s Thumb

- TheAnthroGeek

- This Blog Sits at the

- This Blog Sits at the intersection of Anthropology & Economics

- verbal privilege

- Virtually Islamic: Research and News about Islam in the Digital Age

- Wanna be an Anthropologist

- Welcome to Framing Muslims – International Research Network

- Yahya Birt

Women's Blogs / Sites

- * DURRA * Danielle Durst Britt

- -Fear Allah as He should be Feared-

- a literary silhouette

- a literary silhouette

- A Thought in the Kingdom of Lunacy

- AlMaas – Diamant

- altmuslimah.com – exploring both sides of the gender divide

- Assalaam oe allaikoum Nour al Islam

- Atralnada (Morning Dew)

- ayla\’s perspective shifts

- Beautiful Amygdala

- bouchra

- Boulevard of Broken Dreams

- Chadia17

- Claiming Equal Citizenship

- Dervish

- Fantasy web-log – web-log.nl

- Farah\’s Sowaleef

- Green Tea

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Hilsen Fra …

- Islamucation

- kaleidomuslima: fragments of my life

- Laila Lalami

- Marhaban.web-log.nl – web-log.nl

- Moslima_Y – web-log.nl

- Muslim-Refusenik The official website of Irshad Manji

- Myrtus

- Noor al-Islaam – web-log.nl

- Oh You Who Believe…

- Raising Yousuf: a diary of a mother under occupation

- SAFspace

- Salika Sufisticate

- Saloua.nl

- Saudi Eve

- SOUL, HEART, MIND, AND BODY…

- Spirit21 – Shelina Zahra Janmohamed

- Sweep the Sunshine | the mundane is the edge of glory

- Taslima Nasrin

- The Color of Rain

- The Muslimah

- Thoughts Of A Traveller

- Volkskrant Weblog — Islam, een goed geloof

- Weblog Raja Felgata | Koffie Verkeerd – The Battle | punt.nl: Je eigen gratis weblog, gratis fotoalbum, webmail, startpagina enz

- Weblog Raja Felgata | WRF

- Writing is Busy Idleness

- www.moslima.web-log.nl

- Zeitgeistgirl

- Zusters in Islam

- ~:: MARYAM ::~ Tasawwuf Blog

Ritueel en religieuze beleving Nederland

- – Alfeth.com – NL

- :: Al Basair ::

- Abu Marwan Media Publikaties

- Ahlalbait Jongeren

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Al-Amien… De Betrouwbare – Home

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Wasatiyyah.com – Home

- Anwaar al-Islaam

- anwaaralislaam.tk

- Aqiedah’s Weblog

- Arabische Lessen – Home

- Arabische Lessen – Home

- Arrayaan.net

- At-taqwa.nl

- Begrijp Islam

- Bismillaah – deboodschap.com

- Citaten van de Salaf

- Dar al-Tarjama WebSite

- Dawah-online.com

- de koraan

- de koraan

- De Koran . net – Het Islaamitische Fundament op het Net – Home

- De Leidraad, een leidraad voor je leven

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Faadi Community

- Ghimaar

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Ibn al-Qayyim

- IMAM-MALIK-Alles over Islam

- IQRA ROOM – Koran studie groep

- Islaam voor iedereen

- Islaam voor iedereen

- Islaam: Terugkeer naar het Boek (Qor-aan) en de Soennah volgens het begrip van de Vrome Voorgangers… – Home

- Islaam: Terugkeer naar het Boek (Qor-aan) en de Soennah volgens het begrip van de Vrome Voorgangers… – Home

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- islam :: messageboard

- Islam City NL, Islam en meer

- Islam, een religie

- Islamia.nl – Islamic Shop – Islamitische Winkel

- Islamitische kleding

- Islamitische kleding

- Islamitische smeekbedes

- islamtoday

- islamvoorjou – Informatie over Islam, Koran en Soenah

- kebdani.tk

- KoranOnline.NL

- Lees de Koran – Een Openbaring voor de Mensheid

- Lifemakers NL

- Marocstart.nl | Islam & Koran Startpagina

- Miesbahoel Islam Zwolle

- Mocrodream Forums

- Moslims in Almere

- Moslims online jong en vernieuwend

- Nihedmoslima

- Oprecht – Poort tot de kennis

- Quraan.nl :: quran koran kuran koeran quran-voice alquran :: Luister online naar de Quraan

- Quraan.nl online quraan recitaties :: Koran quran islam allah mohammed god al-islam moslim

- Selefie Nederland

- Stichting Al Hoeda Wa Noer

- Stichting Al Islah

- StION Stichting Islamitische Organisatie Nederland – Ahlus Sunnat Wal Djama\’ah

- Sunni Publicaties

- Sunni.nl – Home

- Teksten van Aboe Ismaiel

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Uw Keuze

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.al-thabaat.com

- www.hijaab.com

- www.uwkeuze.net

- Youth Of Islam

- Zegswijzen van de Wijzen

- \’\’ Leid ons op het rechte pad het pad degenen aan wie Gij gunsten hebt geschonken\’\’

Muslim News

Moslims & Maatschappij

Arts & Culture

- : : SamiYusuf.com : : Copyright Awakening 2006 : :

- amir normandi, photographer – bio

- Ani – SINGING FOR THE SOUL OF ISLAM – HOME

- ARTEEAST.ORG

- AZIZ

- Enter into The Home Website Of Mecca2Medina

- Kalima Translation – Reviving Translation in the Arab world

- lemonaa.tk

- MWNF – Museum With No Frontiers – Discover Islamic Art

- Nader Sadek

Misc.

'Fundamentalism'

Islam & commerce

2

Morocco

[Online] Publications

- ACVZ :: | Preliminary Studies | About marriage: choosing a spouse and the issue of forced marriages among Maroccans, Turks and Hindostani in the Netherlands

- ACVZ :: | Voorstudies | Over het huwelijk gesproken: partnerkeuze en gedwongen huwelijken onder Marokkaanse, Turkse en Hindostaanse Nederlanders

- Kennislink – ‘Dit is geen poep wat ik praat’

- Kennislink – Nederlandse moslims

Religious Movements

- :: Al Basair ::

- :: al Haqq :: de waarheid van de Islam ::

- ::Kalamullah.Com::

- Ahloelhadieth.com

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- al-Madinah (Medina) The City of Prophecy ; Islamic University of Madinah (Medina), Life in Madinah (Medina), Saudi Arabia

- American Students in Madinah

- Aqiedah’s Weblog

- Dar al-Tarjama WebSite

- Faith Over Fear – Feiz Muhammad

- Instituut voor Opvoeding & Educatie

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- islamtoday

- Moderate Muslims Refuted

- Rise And Fall Of Salafi Movement in the US by Umar Lee

- Selefie Dawah Nederland

- Selefie Nederland

- Selefienederland

- Stichting Al Hoeda Wa Noer

- Teksten van Aboe Ismaiel

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- Youth Of Islam

Op zoek naar de profeet Mohammed – De overleveringen via Al-Zuhri

Posted on January 26th, 2012 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Important Publications, Internal Debates, Religion Other.

Gastauteur: Nicolet Boekhoff – Van der Voort

We weten ogenschijnlijk heel veel over het leven van de stichter van de islam, de profeet Muhammad. Elk jaar verschijnt er weer een nieuwe biografie met gedetailleerde informatie over zijn militaire campagnes, zijn huwelijken en zijn dagelijkse bezigheden. Bijna al deze informatie is beschikbaar in de vorm van overleveringen of tradities, in het Arabisch ahadith, die door zijn volgelingen zijn doorgegeven. Deze overleveringen zijn vandaag de dag terug te vinden in verzamelingen die minstens 200 jaar na de dood van de profeet zijn samengesteld.

Enkele wetenschappers hebben de vraag gesteld of deze overleveringen daadwerkelijk de gebeurtenissen beschrijven of latere ontwikkelingen in de islam weergeven. Anders gezegd: gaan ze over de historische Muhammad of over het beeld dat zijn latere volgelingen van hem en de gebeurtenissen hebben, dus om een soort mythische Muhammad? Gaat het om geschiedenis of legende, of misschien iets ertussenin?

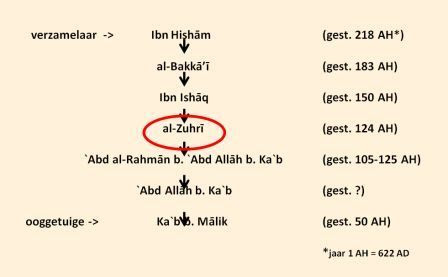

Wat kan helpen om deze vraag te beantwoorden zijn de overleveraarsketens (asanid) die meestal voor de beschrijving van de gebeurtenis staan. De keten zou het pad weergeven waarlangs de overlevering doorgegeven is, namelijk vanaf de samensteller van de verzameling waar de overlevering zich in bevindt, tot aan de ooggetuige van de gebeurtenis, dus bijvoorbeeld via welke personen de verzamelaar Ibn Hisham het verhaal van Ka’b heeft gehoord.

Een van de namen die regelmatig voorkomt in de keten van overleveringen over het leven van de profeet Muhammad, is die van Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri, een beroemde geleerde uit Medina, de woonplaats van de profeet en de tweede heilige stad na Mekka. Al-Zuhri leefde vanaf het laatste kwart van de 7e eeuw tot halverwege de 8e eeuw, wat betekent dat hij zo’n 40 tot 50 jaar na de dood van de profeet Muhammad geboren is. Hij behoorde tot de generatie van de Opvolgers, degenen die geboren zijn na de dood van de profeet en dus zelf geen contact met hem hebben gehad, maar wel overleverden van Muhammad’s metgezellen. Hij had zelf bij een aantal gerenommeerde geleerden uit Mekka en Medina gestudeerd en werkte lange tijd tot aan zijn dood voor een aantal kaliefen van het Umayyadenhof, die het islamitische rijk regeerden van het islamitische jaar 41-132/ ofwel van 661-750 christelijke jaartelling.

Een van de namen die regelmatig voorkomt in de keten van overleveringen over het leven van de profeet Muhammad, is die van Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri, een beroemde geleerde uit Medina, de woonplaats van de profeet en de tweede heilige stad na Mekka. Al-Zuhri leefde vanaf het laatste kwart van de 7e eeuw tot halverwege de 8e eeuw, wat betekent dat hij zo’n 40 tot 50 jaar na de dood van de profeet Muhammad geboren is. Hij behoorde tot de generatie van de Opvolgers, degenen die geboren zijn na de dood van de profeet en dus zelf geen contact met hem hebben gehad, maar wel overleverden van Muhammad’s metgezellen. Hij had zelf bij een aantal gerenommeerde geleerden uit Mekka en Medina gestudeerd en werkte lange tijd tot aan zijn dood voor een aantal kaliefen van het Umayyadenhof, die het islamitische rijk regeerden van het islamitische jaar 41-132/ ofwel van 661-750 christelijke jaartelling.

Het plaatje dat ik op de voorkant van mijn proefschrift heb gezet is dus geen afbeelding van hoe al-Zuhri er waarschijnlijk uit zag, maar geeft weer hoe ik al-Zuhri voor me zag, voordat ik me had verdiept in de gegevens over zijn leven. Voor zijn werk voor de Omayyadenkaliefen werden zijn schulden betaald, kreeg hij een geregelde toelage en een landgoed, dus waarschijnlijk zal hij niet op de grond voor een muur hebben gezeten tijdens het overleveren.

Het plaatje dat ik op de voorkant van mijn proefschrift heb gezet is dus geen afbeelding van hoe al-Zuhri er waarschijnlijk uit zag, maar geeft weer hoe ik al-Zuhri voor me zag, voordat ik me had verdiept in de gegevens over zijn leven. Voor zijn werk voor de Omayyadenkaliefen werden zijn schulden betaald, kreeg hij een geregelde toelage en een landgoed, dus waarschijnlijk zal hij niet op de grond voor een muur hebben gezeten tijdens het overleveren.

Zoals ik al eerder zei is het de vraag of de overleveringen in de latere werken historische gebeurtenissen beschrijven of het beeld weergeven dat latere generaties van hun profeet hadden. Moslimse en niet-moslimse wetenschappers zijn het met elkaar eens dat het overleveringsmateriaal vervalsingen, fouten, tegenstrijdige informatie, verfraaiing van de informatie en dergelijke bevat. In hoeverre is het echter mogelijk om authentiek materiaal van vervalst of gedeeltelijk vervalst materiaal te onderscheiden?

Daarnaast hebben we ook nog te maken met de problematiek van het overleveren zelf. Een verhaal dat overgeleverd wordt van persoon op persoon, hetzij mondeling, hetzij schriftelijk of in combinatie: mondeling op basis van schriftelijke aantekeningen, zal veranderen als het van persoon op persoon wordt overgeleverd. Je kunt dat vergelijken met het doorgeven van een stuk klei. Bij mondelinge overlevering is de klei heel zacht en vervormd makkelijk. De kern blijft hetzelfde zijn, maar de vorm zal anders zijn, zoals andere woorden, andere volgorde van het verhaal. Bij mondelinge overlevering obv aantekeningen heb je te maken met zachte klei met harde stukken erin. De zachte stukken kunnen vervormen, maar de harde stukken, de notities, die opgeschreven woorden, blijven vaak hetzelfde tijdens het overleveren. Bij schriftelijke overlevering, wat hardere klei, zijn er weinig veranderingen, hoewel er een stuk vanaf gehaald kan zijn of er kleine vervormingen in de klei zijn. Bij schriftelijk moet u denken aan het dicteren van een tekst of het controleren van een tekst die een student voorlas aan zijn leraar.

Elke overleveraar zal vingerafdrukken op de klei achterlaten in de vorm van woordjes, stukken tekst, verhaalelementen die alleen bij die overleveraar (en zijn studenten) te vinden zijn. Om te kijken of de overleveringen in de latere werken die aan al-Zuhri zijn toegeschreven, ook echt van hem afkomstig waren, ben ik bij drie verhalenop zoek gegaan naar zijn overleveringsvingerafdrukken. Daarvoor heb ik zoveel mogelijk varianten van dat verhaal verzameld. Ik heb alle ketens van de teksten in een diagram bij elkaar gezet, wat het volgende plaatje oplevert. Ik heb de versies van al-Zuhri’s studenten met elkaar vergeleken. Elke versie had een of meerdere kenmerken die niet bij de andere studenten te vinden waren, van elke student heb ik een overleveringsvingeradruk terug kunnen vinden. De versies van de vier studenten hadden ook veel gemeenschappelijk, wat de gegevens uit de overleveraarsketens bevestigt, want ze zijn allemaal van al-Zuhri afkomstig.

Om te controleren of al-Zuhri zijn overlevering vervolgens ook van de persoon had die hij in de keten als zijn informant aangeeft (de vier namen uit het schema bleken van een en dezelfde persoon te zijn), heb ik al-Zuhri’s versie vergeleken met een of meerdere versies die volgens de overleveraarsketens niet van hem afkomstig waren. Het bleek dat alle drie de verhalen inderdaad van al-Zuhri afkomstig waren en dat alle versies van zijn studenten van elkaar verschilden en karakteristieke overleveringsvingerafdrukken bevatten. Dit betekent dat bewezen is dat al-Zuhri’s studenten het verhaal van hun leraar hadden gekregen en het weer verder overleverd hadden. De versies van de studenten lijken echter zo veel op elkaar dat al-Zuhri hen moet hebben onderwezen op basis van uitgewerkte notitieboeken.

De analyse heeft ook laten zien dat de versie van een student van al- Zuhri, Ma’mar b. Rashid, afweek van die van de andere studenten. De versies van de andere studenten waren meer uitgewerkt dan die van Ma’mar en leken in veel gevallen ook sterk op elkaar. Voorbeelden van uitwerkingen zijn locaties die in Ma’mar’s versie vaag aangeduid zijn, maar in de versies van de andere studenten benoemd. Namen van personen die in Ma’mar’s versie afgekort zijn, zijn bij de anderen volledig vermeld. Bepaalde verhaalelementen zijn wel aanwezig in Ma’mar’s versie, maar over het algemeen genomen niet bij de anderen en vice versa.

De Umayyadenkalief Hisham heeft al-Zuhri waarschijnlijk in zijn laatste decennium ertoe aangezet om een boekwerk voor het hof te maken. Later heeft al-Zuhri ook studenten buiten het hof van de kalief deze boeken laten overschrijven. Andere resultaten waren dat al-Zuhri’s drie overleveringen teruggingen op verhalen uit de tijd rond de eeuwwisseling of eerder en dat hij zijn materiaal bewerkt heeft tussen de tijd dat hij het ontving en de tijd waarin hij het aan zijn studenten ging overleveren, waarbij hij overstapte van aantekeningen voor persoonlijk gebruik tot meer of minder uitgewerkte notitieboeken. Bij hem is een trent waarneembaar om zijn bronnen beter te specificeren en een groeiende belangstelling voor het verband van verhalen over de profeet met Koranverzen en juridische zaken. Langzamerhand ontstaat er zo meer kennis over de ontwikkeling van de biografie van de profeet Muhammad in de tijd voor de grote verzamelingen.

Nicolet Boekhoff (Utrecht, 1970) studeerde Talen en culturen van het Midden-Oosten (specialisatie Islam) aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. Ze was als junioronderzoeker tussen 2002 en 2008 werkzaam bij de afdeling Arabisch en islam van de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. Momenteel is ze docent bij diezelfde afdeling. Dit onderzoek valt onder het programma van het Research Institute for Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies van de Radboud Universiteit. De tekst van dit stuk is uitgesproken tijdens het zogenaamde lekenpraatje aan het begin van de verdediging van het proefschrift. Afgelopen maandag vond de verdediging plaats. De titel van haar proefschrift is Between history and legend. The biography of the prophet Muhammad by Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri.

Fantasy, action and the possible in 2011

Posted on December 18th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Headline, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Guest Author: Samuli Schielke

This essay is about Lenin, Tahrir, Islamists, poetry, choice and destiny in an attempt to provide some sort of theoretical synthesis of a confusing experience. It is the very slightly modified transcript of a lecture I gave at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte on 6 December 2011.

First of all, thank you very much everybody for coming here. I had no way to expect if I would get an audience of two or twenty, and it turned out to be more than twenty. I’m very happy about that. Thank you very much to Joyce Dalsheim and Gregg Starrett for inviting me here. And thank you to the University of North Carolina, and the Department of Anthropology and the Department of Global, International and Area Studies. This is a wonderful occasion to try to make some general sense of something which is very confusing: anthropological fieldwork in times of political and social transition. I have been writing a blog, and in every blog entry I have been presenting a different theory that has contradicted the previous day. It is very difficult to make any general kind of theory these days, but I’ll try to take the challenge offered to me in the shape of this presentation, and do some of that.

I’ll start with a little jump to history, because I think that the question which I try to tackle, which is that of the possible – the question: What is to be done? What can one do? Can what I do make a difference? Do I have a choice, and what kind of choices do I have? – is a question that was perhaps theoretically developed in relation to the revolutions more than hundred years ago by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, the to-be leader of the Russian revolution, who in 1901 wrote his very influential pamphlet What is to be done? It is an interesting book to read for various reasons, and I want to open up with it, because he really poses the revolutionary question about the possible in a sense that deals with the tactics, and the conditions one must be able to create to change the paths of action.

Lenin’s book is basically a critique of the social democratic movement, it’s all about polemics against other socialists, and as such it is not very interesting for readers of our times. But it becomes interesting when he argues why the social democratic movement needs a vanguard of professional revolutionaries – because that is Lenin’s answer to the question about hat is to be done: In order to have socialism one must be able to create a vanguard of professional revolutionaries who are able to spread propaganda to all sorts of classes, and when the breaking point of the system comes, they are there, ready to take over. But Lenin also says is that this is a dream. This is a wildly unrealistic, fantastic kind of expectation: to have an all-Russian socialist newspaper, and a secret party apparatus that is there everywhere. But he says: It is a dream, and a revolutionary movement must be able to dream. If it doesn’t, it will become the victim of its own caution.

Lenin’s pamphlet is worth reading also in 2011, the year of the Arab uprisings, for various reasons. One reason is that he was successful. His plan actually worked out. And second, because his success was a terrible one. Lenin offers us a key question: What is to be done? – and a key clue, which is dreaming, fantasy. But he also offers us the historical case of a successful revolution that resulted in a devastating civil war, and, less than twenty years later, in the mass terror by Stalin that killed tens of millions of people. So it is also a very good reminder not to be too romantic about revolutions.

There are moments when revolutions are necessary, and in the Middle East it has come to this point. But even when they are necessary and justified, they are terrible. Things get destroyed, people get killed, and in the end the wrong people seize the power. This has happened in Egypt. The economy is at a standstill. At least a thousand people have been killed. And there seems to be no immediate end to the violence as long as the country is ruled by a military dictatorship that is very brutal in the ways it deals with protests. And it looks like Egypt will be governed for the next couple of years by an uneasy alliance of military rule and Islamist parties. All in all it would look like one should make a sceptical assessment of the current state of the revolution. At the same time, I must add that as a researcher I am a very decided supporter of the Egyptian uprising – so much that in my own work this year it has become very difficult to distinguish between ethnographic analysis and revolutionary propaganda. But I do not support the idea of the Egyptian revolution or the Arab uprisings for their own sake. There is nothing in revolutions that would be valuable for their own sake. They are valuable only insofar they open spaces that didn’t exist before: space to think, to say, to pursue things, to realise things that were inconceivable, or at least unlikely or frustrating just a year ago. And this has definitely changed.

This year in Egypt has been a time of transition when all kinds of people have been struggling with this question, which in Arabic is actually a proverbial question: eh il-‘amal? What is to be done? It is a vast field but I will take us through three concrete case studies which I run through quite hastily: One is revolutionary action; the other one is the dream of the Islamic state; and the third one is literary fantasy. They are all related in quite interesting ways.

Revolutionary action

Revolutionary action is the one which you probably all are better informed about, because it has been very present in the media in the shape of Tahrir Square, in the shape of witty revolutionary activists who speak good English and very capable of conveying their message to the world audience – an important role! It has now become fetishised, it has become copied by various kinds of social protest, it has become a tourist product. The American University in Cairo Press is selling not less than three different glossy coffee table books about the revolution. But it is important to remember that when it originally happened, its power was in its surprising nature. It took everybody by surprise. It took the government by surprise, it took ordinary people by surprise, it took – and this is the most interesting thing – the revolutionaries themselves by surprise.

People went out on the streets not knowing what would happen, not expecting what they could possibly accomplish (inspired and hopeful, however, by the example already set by the Tunisian revolution), but simply angry and frustrated about years and years of social experience that offered them over and over again great expectations of good life and over and over again had disappointed these expectations. People were combining an extreme sense of anger and frustration with a very simple step to occupy the streets that had not been possible in Egypt before. The moment it became possible, the entire picture changed. It required very little in material terms. It required simply the possibility of enough people to occupy streets and to hold out against the police – which had been impossible since 1977, when there was the last uprising in Egypt, which failed. This very moment created a completely new situation, so much that it has become a sort of fantastic, utopian, almost religious moment. Ever since the protesters were able to occupy Tahrir Square in Cairo and other squares across the country, this moment of standing in the square has developed into something that now is an essential part of any idea of changing the country by means of revolution.

When I talk about revolution, I refer specifically to a group of people whom I describe as radical revolutionaries, those people who expect the country to fundamentally change, the people to change, the way the country is governed to change. It is not necessarily related to a political agenda. Most people who feature as radical revolutionaries would in Egyptian terms be liberal or left, but there are also Islamists among them who believe in religious government but don’t believe in the established Islamist parties. This radical revolutionary group, which is a small minority – I think the active core is maybe tens of thousands in a country of 80 million people, and its wider supporters may be about a quarter of the population – has turned this moment of standing in the square into a dynamic continuously surprising momentum that has at the same time amazing powers and deep limits.

Its primary power lies in its spontaneous and surprising nature. We saw this in the 18 days of the revolution in January and February when this ongoing pressure from the street made any attempt to strike a nice neat deal between the government and the opposition impossible, because there was nobody to speak to. There was no revolutionary leadership that could sell the revolution. The movement could not be betrayed by its leaders because it did not have any. This has repeatedly happened, most recently in the events this November, when very brutal violence by the Military Police did not crush the revolutionary movement. Instead of running away and being scared, people flocked into the square. There was again a spontaneous reaction. This has created a form of spontaneous resistance that is able to thwart any attempt of authoritarian restauration, over and again.

However, we should be very careful not to glorify this standing on the square too much. When I speak with people there, there is sometimes this idea that this square is what it’s all about. In order to change the country we need to have revolution, we need to have more revolution. It becomes limiting. When we go back to one year ago, nobody could really even dream of this moment. Now that it has become not only possible but material, it has gained such power over the radical revolutionaries’ imagination, that it has become difficult for them to think of any other way of changing this country.

This has become very evident in the elections where the revolutionary fraction received a fraction of the vote that is actually less than their already small numbers. Most of the revolutionaries failed (or refused) to participate in any kind of election campaigning because they were distrustful of the parties, considering all the parties corrupt and interested in sharing the cake of power and not interested in what the people need – which is all true. If you distrust the Islamist parties in Egypt you should see who is running Egypt’s liberal party: Egypt’s second richest man. There is not much to be expected from that side either. But this distrust also means that there is an incapability of taking to the streets outside the square. It is related to the difficulty of organisation, it is related to lack of funds – for example, certain groups have huge amounts of money. Other groups don’t. When it comes to spreading leaflets, you need to print them and you need to pay money for that. It becomes quite a concrete problem.

Occupying the square is a very ambiguous form of social protest and of changing the country. This was very much seen in the events of the end of November when at first, a new uprising took surprised everybody. Friday 18th of November witnessed big demonstrations which were lead by Islamist parties who were using these demonstrations in order to strike a better power sharing deal with the military, in which they seemed successful. These were cautious demonstrations, and the supporters of the Islamist parties were not making any chants aimed directly against military rule, only against certain ministers. That evening, I was in Alexandria, and some of the young leftists – who had also been in the demonstration but had left it early because they found that the Salafis, the radical Islamists, were dominating it – were very pessimistic. Their sensibility was that the revolution had now really lost. Next day, one hundred and fifty people staged a sit-in in Tahrir Square. The police came to break the sit-in with force, but these one hundred and fifty people were enough to create a momentum where thousands of angry people flocked into Tahrir Square, entered a days-long fight with the police whereby more than forty, possibly one hundred protesters were killed, and forced the Military Council to change the cabinet (even if that of course means nothing). There was a huge breakup of the situation, everybody was shaking – end then the elections came.

This time, the protesters were surprised. They had surprised themselves, surprised the government, surprised the Muslim Brothers who had become very defensive. They had seized the momentum, they had once again half a million people on the square, then came election day. The revolutionaries had thought that the elections will fail, that the Military Council doesn’t want to let them go through anyway, that they will sink in a wave of violence, that the elections are pointless. The elections were successful. There was a 62% voting turnout in the first round, which in Egypt is a historical record – usually the voting turnout been more like 6,2%. It broke the neck of the new uprising because people were suddenly happy. They were happy that they could vote. And in order to have an uprising you need people to be angry.

So again, there was a new surprising moment which showed that the way to the square lacked the capacity, the imagination to go other ways. The revolutionaries standing in the square at that moment actually lacked the fantasy to realise what the elections could possibly mean for Egyptians.

Islamic state

The elections are now bringing a landslide victory of Islamic religious parties. I was just reading the results of the first round – we don’t have the final results because the elections take place in three rounds, different provinces voting at different times (the electoral law requires every polling station to be supervised by a judge and there are not enough judges in the country). One third of Egypt’s provinces have voted now. The results show that about sixty per cent of the vote of the party lists go to two Islamist party alliances, one of them the Muslim Brotherhood who are conservative, and one of them the Salafis who are badass fundamentalists. This has completely surprised some people, but anybody who has actually been following the situation in the streets has not been surprised at all. Actually the Muslim Brotherhood got less votes than one would think. With 36% of the vote, they actually did badly. They should have gotten 50%.

In a country that just had a revolutionary uprising against a corrupt system that was not an uprising in religious terms but one in terms of social justice, or freedom, or human dignity, why did people vote for Islamic parties? One of them, the Muslim Brotherhood, supported the revolution (but sided with the Army very soon afterwards), the other, the Salafis, were actually supporting Mubarak. Why did people vote for them?

The first thing to remember is of course, again, that the revolutionaries are actually a minority in Egypt. The majority of people were never quite that enthusiastic about the revolution. They were enthusiastic once it was successful, but as long as it was still happening they were rather afraid. But there is more to it than that. It is important to realise that this sort of revolutionary enthusiasm and action was not the only thing that has been going on in Egyptian society. Lots of other things have been happening.

One of the things that have been happening for decades is a sense of a moral crisis. Of course, moral crisis is nothing special. People who study morality say that they have never encountered any society that does not have a moral crisis of some sort. Describing things as being in a crisis seems to be essential to moral imagination. But I would say that there has been a serious moral crisis that has to do with the fact that traditional Egyptian conservative, very family-oriented, very much relying on patriarchal alliances, clear hierarchies of age and gender, has become more and more destabilised, first by Arab socialism in the 50’s and 60’s, and then in a more subtle way by consumer capitalism since the 1970’s. It has made people to live more individualised lives, and it has made people’s livelihood in most cases immoral, illegal, and against Islamic principles: stealing, taking bribes, cheating, all kinds of questionable stuff. This is a society where there has emerged an enormous expectation for something that is morally sound. And Islamists can offer that promise. They offer a God-fearing government, a government that is morally sound and does not steal from its citizens.

This is another great dream, one that has not been so much the dream of the people who went out to the streets against Mubarak, but the dream of a much vaster part of the population: Can’t we just have a leadership that is good? Can’t we have a pious, decent person running this country? This is a different kind of dream as compared to the revolutionary dream of transforming the ways in which the country is governed (one focussing on the process and practice of government, the other on the characters of the people in the government), and it leads to different consequences. One of the major consequences is that Egyptians who would not be Islamist radicals in any proper sense, who would think about life in very pragmatic terms, who would be sometimes more conservative and sometimes more liberal, would nevertheless in doubt cast their vote for a religious candidate because they think: We want to give them a try.

The Islamist parties have played their cards very well. The revolutionary fraction, including also breakaway Islamists, has huge problems to compete with these large organisations that have huge amounts of money, that have social welfare projects, and that speak to the people. How do we actually struggle with this? This struggle has so far brought a very important lesson: If you don’t want to just change the government but if you actually want to change the way society works and the way people think about society, if you want to win elections, if you want to have majorities behind you, it is necessary to have something which people cannot disagree about.

This is the power of the Islamist movements in Egypt. Most people think of them as politicians. They don’t actually have full trust in them. As said, their support of an Islamic government is a conditional one. They know that politicians lie. Islamist politicians lie, too. There is no question about that. Many think that they are too extremist, too uptight, but they cannot disagree that these are pious people and that they speak the word of truth. They speak about Islam, and that is true. I don’t like you, but what you say is true. This seems to be crucial when we once again ask Lenin’s famous question: What is to be done? A crucial answers to that question is to be able to develop an ideological standpoint that stands beyond critique in a specific social setting.

The revolutionaries actually have a couple of these. One is the hatred towards all kinds of governmental oppression. This is something on which they rely all the time. One is the promise of dignity and freedom. Right now the Muslim Brotherhood has been able to rally on this promise. It depends on their ability to deliver whether the more radical fraction will be able to reclaim it from them. One in particular has tremendous power: The blood of the martyrs of the revolution is an enormously important asset for the radicals.

We have learned to think of Egypt’s revolution as a peaceful one. It was peaceful because the protesters didn’t carry weapons. But it was not peaceful in the sense that nobody would have gotten killed. A thousand people got killed, and the fact that a thousand people got killed has become the primary power and asset of any radical revolutionary action. Whatever there comes a tactical politician or a Salafi, the radicals can say: Where were you when the martyrs got killed? This is very consciously employed now by the radical fraction which last Friday staged a symbolic funeral for the people who had been killed most recently. And this is once again a reminder not to romanticise revolutions. It is easy to romanticise revolutions, and it is even easier to romanticise peaceful revolutions. But peaceful revolutions, too, need people getting killed.

The question that remains now is: Why could the Islamists in particular seize the day in the elections, and why could the radical revolutionaries not? Why could they, in turn, seize the day and surprise everybody on 20th of November but then lose the momentum? This is a question about what kind of actions are conceivable, and how one can actually change the scope of conceivable actions. What kind of actions have people learned to be good at, and how can people in such transitional state try to learn different kind of actions?

Literary Fantasy

I take quite a detour and turn to literary fantasy. The revolutionary year of 2011 is a year that constantly runs ahead of fantasy. Things happen, and people keep getting surprised, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. Sometimes it’s a disaster, sometimes it’s fantastic. It is interesting to go after the issue of fantasy itself, because literature has a lot to do with this uprising.

The ground has been prepared, especially for the more educated parts of the population, by a growing wave of socially critical writing. Blogging has been studied most intensively but actually blogs are just one part of a big scene of people exchanging facebook posts, publishing books, reading poetry in cafes. I recently saw some friends of mine sitting in Tahrir square – they were protesters camping there since a week – and reading from a poetry collection by Amal Dunqul who at the moment has become one of Egypt’s most famous poets. He wasn’t quite that famous before last year. Amal Dunqul (1940–1983) was a communist poet who in the 60’s and 70’s wrote extremely pessimistic and critical poetry. He was against everything. He was against the Camp David Agreements two years before they were signed. He was against any kind of concession to power. He the was the personified refusal. He had one of these famous lines opening one his poems: “Glory to Satan who said no in face of those who said yes.” (Last Words of Spartacus, 1962) In a very religious society like Egypt this is a dramatic way of thinking. Now, people frequently cite this verse.

I had a meeting with a group of teachers in a poor neighbourhood of Alexandria who were writing poetry, and we started talking about this. – This is actually my new fieldwork, which is not about revolution, it’s about writing. I hop I can get rid of this revolution stuff and back to the issue of writing… – We started talking about Amal Dunqul. What did this verse (and others) by Amal Dunqul do, what did it accomplish? There emerged two competing theories. Of course, I lean for the other, but it is important to cite both theories.

One of the two theories was argued for by the poet and teacher Hamdi Musa who said: Literature changes nothing. Look, Hamdi says: Every other cafe in Egypt has Qur’an recitation running on all the time, but the people sitting in the cafe are not getting any more pious from it. If the word of God doesn’t do it, how could my writing change anything? He says that literature is only about immediate personal pleasure. If it is transformative in any way it is transformative to myself. But then others argued: No, that’s not true. Literature changes one’s outlook at the world. It offers something to think about. In the first theory, literature changes nothing, and we are now in Egypt reading Amal Dunqul because something happened and he gives a voice to something that was happening anyway. The other theory says: Because we have been reading Amal Dunqul we think about the world differently, we value protest, which we wouldn’t do if we hadn’t read Amal Dunqul.

My good friend and research assistant Mukhtar Shehata turned the second theory into a dialectical model of fantasy, dreams, and decisions. ( http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=284111558280237) Fantasy, he says, is a space of freedom, completely free from any need to realise it. It depends on what we know and our material conditions; it is not free in the sense we could imagine anything. But it is a space of freedom where we can think up something and we don’t have to worry whether it can happen or not. Fantasy, Mukhtar says, is the ground from which we develop dreams (ahlam in Arabic), in the sense of aspirations. A dream is something that calls to be realised: It is my dream to marry, it is my dream to become a university professor, it is my dream that the world will be a peaceful place – it is all something that calls for realisation. Dreams, then, become something that guide people’s actions. Because they guide people’s actions they make people find themselves in situations where they have to make decisions.

His example is private tutoring. In Egypt, private tutoring is the main income of teachers who are very badly paid. So for everybody who goes to school, the actual studying takes place in the evening in private tutoring, which costs a lot of money. He gave up private tutoring after the revolution. On one occasion, he was speaking with another teacher about it, and his point was that you first have to think, imagine that there could be something else than private tutoring. That is the first step. Second, you have to start to desire it: If only I could live without private tutoring! The third step is that of decisions, of it leading you to moments where you can actually say: No, I’m not going to do it. I do something else. – And this, then, changes the material ground of reality because you make certain choices, and these choices bring you new experiences, and these new experiences create new grounds of fantasy, and the circle goes on.

This could, of course, be easily put into the shape of a liberal or neoliberal idea where everything is about choices, decisions, character, building my capacities, etc.

This calls for caution. When we talk about decisions and choices, we also have to talk about the inevitable. You cannot study the possible without thinking about the inevitable. In Egypt, when you talk about choice, people start talking about destiny (nasib). It’s not in my hand, it’s in God’s hand: I want to marry this girl but in the end I marry somebody else and I accept it. In Egypt, the inevitable usually takes religious shape as the will of God. But no matter what theoretical shape we give to the inevitable, be it the will of God or if it is the material conditions of production in a Marxist theory, the fact is that any sort of choices and decisions have to reckon with the inevitable. We live in a world where our character is cultivated and our choices made under specific conditions that direct and encourage what we can do. But the trick is that our own fantasy is one of these material conditions. Fantasy is not something that is fundamentally different from the ground I am standing on. It is part of these conditions that direct what I can do.

This leads us back to the question about why some people could seize the day in certain moments, and not in other moments.

We are talking here about choice and freedom as limited freedom. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a phenomenologist philosopher argued in the 1940’s that Human freedom exists only within limitations. Limits are not against freedom. Freedom is only there because there are limits against which we experience our freedom. In Egyptian Arabic this is described with the verb yitsarraf, which means to manage in circumstances that are not of your own making. This is the condition of any answer we give to the question of what is to be done.

Any specific answer, any specific trajectory relies on its own material means and possibilities – the Islamists having vastly more money, for example, and the radical revolutionaries being very well connected to the international media. You have different material advantages that make it possible to do something. But it is also fundamentally related to having learned to anticipate certain kind of situations and to master them well. In a very short time the radical revolutionaries have learned to occupy Tahrir. They have learned to do it so well that in this November they just mastered it. It is a most amazing example of self-organisation. Without any leadership, actually even prohibiting parties and speakers’ stages, they managed to make a much better organised uprising than they did in January. But at the same time, it means that they are really bad at anything else. If you look at the Muslim Brotherhood, they have for decades mastered tactical manoeuvring between an authoritarian government and citizens who want to have a good religious government and society. They have been so good at this manoeuvring that when these elections came and they seemed to win with 36% of the vote but actually lost because they should have gotten 50%, this was because of their mastery of tactical manoeuvring. For the radical revolutionaries, even of Islamist leanings, they became unelectable because they showed absolutely no backbone. A big part of people with Islamist leanings in Egypt who really wanted to have a religious government didn’t vote for the Brotherhood because they thought: We really don’t know what these guys are going to do. (This was a reason for many to vote for the more radical Salafis instead, whose stance and programme are quite clear) Their particular knowledge and imagination of what could be done got them a very strong popular support but also brought specific limitations.

The really interesting question, then, is: How and when can people adapt their knowledge and imagination? My conclusion, a very short one, is that the really revolutionary task is to accomplish a shift in the way people look at the world and understand the scope of what they can do, which leads them to act in a different way. This shift requires fantasy. It requires a kind of active fantasy: not just the kind of passive fantasy of imagining whatever one already was used to, but rather a continuous engagement of going beyond the limits. This is why the Egyptian revolution was possible in the first place: because this shift happened. But its future will very much depend on how different actors in the scene will come to develop their expectations of what is possible (and what inevitable), that is, come up with new answers to Lenin’s question about what is to be done.

Samuli Schielke is a research fellow at Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), Berlin. His research focusses on everyday religiosity and morality, aspiration and frustration in contemporary Egypt. In 2006 he defended his PhD Snacks and Saints: Mawlid Festivals and the Politics of Festivity, Piety and Modernity in Contemporary Egypt at the University of Amsterdam, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences. During his stay in Cairo at the time of the protests at Tahrir Square he maintained a diary. The text here is part of that diary which you can read in full at his blog. He also wrote “Now, it’s gonna be a long one” – Some first conclusion on the Egyptian Revolution, The Arab Autumn? and Egypt: After the Revolution

‘Symbolische uitburgering’ en de neonazi moorden in Duitsland

Posted on November 29th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Misc. News.

Guest Author: Daan Beekers

Een nachtwake voor de slachtoffers bij de Brandenburger Tor, een grote demonstratie in mijn wijk Friedrichshain en constante aandacht op radio en TV: tijdens de afgelopen weken die ik in Berlijn doorbracht stond de publieke discussie hier in het teken van de door neonazi’s gepleegde moorden op negen middenstanders met een migrantenachtergrond (mit Migrationshintergrund zoals dat hier heet), acht van Turkse en één van Griekse afkomst. Deze moorden werden tussen 2000 en 2006 op verschillende plekken in Duitsland gepleegd en stonden bekend als de ‘döner-moorden’ (twee van de slachtoffers hadden een döner-zaak). De ondernemers werden allen, schijnbaar in koelen bloede, in hun eigen zaak doodgeschoten. Tot voor kort waren de daders niet gevonden.

De recente ontdekking dat drie neonazi’s verantwoordelijk waren voor deze moorden, en voor nog een moord op een politieagente, bracht een grote shock teweeg in Duitsland (de daders behoorden tot de terreurgroep Nationalsozalistischer Untergrund; twee van hen zijn dood aangetroffen na een mislukte bankoverval, de derde heeft zich bij de politie gemeld). Het nieuws maakt duidelijk dat de moorden zonder aanzien des persoons zijn gepleegd, om geen andere reden dan de buitenlandse afkomst van de slachtoffers. (more…)

Voor Jonge Turken doet Nederland er niet toe

Posted on November 8th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Multiculti Issues, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Voor Jonge Turken doet Nederland er niet toe

Guest Author: Zihni Özdil

Turken in Nederland worden gediscrimineerd – zeker. Maar velen van hen doen niets om de vooroordelen weg te nemen.

Het opiniestuk van Tuncay Cinibulak over de ‘Turks-Koerdische rellen’ in Nederland bevat een aantal analytische fouten en een misplaatste causaliteit. Cinibulaks stuk illustreert dat de integratie van de Turken in Nederland bij lange na niet is voltooid.

Ten eerste maakt Cinibulak een fout die je in veel reacties op de rellen terugziet: hij noemt de relschoppers ‘jonge Turken en Koerden’. Het zijn in werkelijkheid jonge Nederlanders wier (groot-)ouders afkomstig zijn uit Turkije. Deze jongeren zijn in Nederland geboren en zullen uiteindelijk ook hier sterven. Deze vanzelfsprekendheid wordt bijna vijftig jaar na de arbeidsmigratie nauwelijks onderkend door de meeste Turkse Nederlanders.

Het klopt dat de ontvangende samenleving ‘allochtone’ Nederlanders altijd als ‘de anderen’ heeft gezien. Zo is er nog steeds veel discriminatie in Nederland, zoals bleek uit recent onderzoek van de VU naar de bereidheid van uitzendbureaus om allochtonen desgevraagd voor vacatures uit te sluiten. Ook het uitgaansleven is notoir racistisch.

Door de opkomst van het rechtspopulisme zijn Nederlanders met een moslimachtergrond bovendien gereduceerd tot ‘kopvodden’ en ‘straatterroristen’. Voor die tijd was Nederland in de houdgreep van de eigenlijk net zo uitsluitende multiculturalisten. Omdat de integratiegraadmeter voor multiculturalisten altijd is geweest de mate waarin een groep overlast veroorzaakt, werden de Turken dus als redelijk goed geïntegreerd gezien.

Waarom? Ze stelen geen handtasjes, vinden onderwijs belangrijk en voldoen aan het sociaal-economisch ideaal van de kleine burgerij. Dat de bedrijvigheid van veel Turks-Nederlandse ondernemers – shoarmazaakjes, semicriminele belhuizen en bakkerijen in zwarte wijken – zou bijdragen aan integratie is op zijn zachtst gezegd twijfelachtig. Het wordt in elk geval niet gestaafd door onderzoek, mits we een realistische definitie van integratie zouden hanteren, namelijk de sociale, maatschappelijke en culturele binding met Nederland.

In het multiculturele tijdperk werden voormalige gastarbeiders en hun nakomelingen gestimuleerd zich vooral in een geprefabriceerde en gesubsidieerde zuil te bewegen. Turkse Nederlanders waren hier bij uitstek zeer goed in. Verstopt in organisaties die banden hebben met dubieuze religieuze of ultranationalistische clubs uit Turkije waren de Turken goed aan het ‘integreren’. Cinibulak stelt terecht dat de recente rellen geen acties waren van losgeslagen jongeren. Maar hij legt het verkeerde causaal verband als hij stelt dat de oorzaak ligt in een ‘nieuwe fase’ van het Turks-Koerdische conflict. Ook schetst hij een ongefundeerd doemscenario: ‘De frustraties en de woede van de Turkse jongeren komen nu nog impulsief tot uiting. Maar het kan niet worden uitgesloten dat ze zich op een kwaad moment ook op de Nederlandse samenleving afreageren. Zo beschouwd, kunnen de rellen worden opgevat als een mogelijke voorbode van een nieuwe geweldsgolf.’

Cinibulaks stelling dat jonge Turken en Koerden in Nederland goed Nederlands spreken en vertrouwd zijn met de Nederlandse omgangsnormen is in regelrechte tegenspraak met de feiten: ‘De taalachterstand is het grootst onder leerlingen met een Turkse achtergrond (…) Turken zijn in hun contacten meer gericht op de eigen groep dan Marokkanen. Hierin is de afgelopen tien jaar weinig veranderd’, aldus enkele conclusies van het SCP.

In tegenstelling tot Cinibulaks beschrijving waren de rellen niet impulsief en ook geen nieuwigheid maar een te voorspellen actie binnen een vast historisch patroon. Net als in de jaren negentig en in het afgelopen decennium komen ook nu honderden jonge Turkse Nederlanders georganiseerd – door de Grijze Wolven in dit geval – in actie als het Turks-Koerdische conflict escaleert. Elke keer kwam het daarbij tot rellen in Nederland met soms doden als gevolg. Volgens onderzoek kijkt bijna 70 procent van de Turkse Nederlanders dagelijks naar Turkse tv-zenders. De verontwaardiging die de Turkse media ventileerden na de aanslag op Turkse soldaten, werd dus direct overgenomen door (jonge) Turkse Nederlanders. Op internet lieten ze blijken hoezeer ze begaan waren met ‘hun land’ en ‘hun soldaten’.

Cinibulak wijst op de vele, goed gedocumenteerde, sociaal-psychologische problemen die Turks-Nederlandse jongeren ondervinden. Maar net als de verontruste Turken die in januari een manifest opstelden, ziet Cinibulak deze jongeren vooral als zielige slachtoffers van ‘de Nederlanders’. Ik bestrijd dat. Deze jongeren zijn zelf ook Nederlanders en zijn allesbehalve zielig. Ze zijn intelligent en hebben veel potentie.

Maar hun toekomst in Nederland ligt in hun eigen handen. De meesten kiezen nog te vaak voor de makkelijke weg. In plaats van de op Turkije gerichte ketens van hun (groot-) ouders en al die organisaties van zich af te werpen, omarmen ze die juist.

In plaats van de mouwen op te stropen en zich samen met hun Marokkaanse, Surinaamse, Antilliaanse en autochtone landgenoten in te zetten voor een toekomst in Nederland zonder discriminatie en uitsluiting kiezen ze ervoor om alleen in actie te komen voor Turkije.

In april hield ik in Den Haag een toespraak tijdens een manifestatie tegen de onderwijsbezuinigingen. De Turkse studentenverenigingen waren uiteraard afwezig, en dat was te verwachten. Deze verenigingen ‘integreren’ liever door middel van het organiseren van jaarlijkse iftar-diners, Istanbul-reizen en enkele gastsprekers uit Turkije.

Cinibulak beseft niet dat de kern van het probleem ligt in de begrijpelijke maar op lange termijn funeste zelfidentificatie van deze jongeren. Hun Turkse afkomst is niet een erfgoed dat hun Nederlandse identiteit aanvult. Integendeel, anno 2011 zijn de Turkse ‘Blut und Boden’ juist de allesbepalende identiteit voor veel van deze jongeren.

Ik spreek regelmatig met uitwisselingsstudenten uit Turkije, en zij zijn altijd ontzettend verbaasd wanneer ze zien hoe conservatief en nationalistisch de Turkse jongeren in Nederland zijn.

De overmatig op Turkije gerichte organisaties in Nederland houden de geslotenheid van de gemeenschap en daarmee ook de schizofreen te noemen zelfidentificatie van jonge Turkse Nederlanders in stand. Fysiek leeft men in Nederland maar Turkije is vaak het enige land waar men zich werkelijk om bekommert. Het publieke debat over maatschappelijke kwesties in hun eigen land gaat grotendeels aan deze jongeren voorbij.

Zihni Özdil is docent en promovendus maatschappijgeschiedenis aan de Erasmus Universiteit. Dit opiniestuk verscheen in de Volkskrant (07 november 2011). Dit stuk is ook te lezen op zijn eigen site: zihniozdil.info

The Arab Autumn?

Posted on October 12th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Guest Author: Samuli Schielke

I never liked the expression “the Arab Spring” because I know too well what happened to the Prague Spring in 1968. A short time of hope in a “socialism with a human face” was crushed by Soviet tanks, and it took more than twenty years before a new revolution could gather momentum.

2011, the year of revolutions and uprisings around the Arab world, has been marked not only by an amazing spirit of change, but also by fierce resistance by the ruling elites, and a fear of instability and chaos among large parts of the ordinary people. Some uprisings, most notably that in Bahrain, were crushed with brute force at an early stage. Others, in Yemen and Syria, continue with an uncertain future. Along with Tunisia, Egypt appeared to be one of the lucky Arab nations that were able to realise a relatively peaceful and quick revolution, a turning point towards a better future of justice, freedom, and democracy. This autumn, however, the situation in Egypt raises doubts about that better future.

Returning to a different country

I returned to Egypt on October 2nd, this time not with the aim to follow the events of the revolution but to begin a new ethnographic fieldwork on writing and creativity, pursuing questions about the relationship of fantasy and social change. I found Egypt in a very different state from what it had been when I left it behind in March. Returning here, I encountered an air of freedom, a sense of relaxation and ease, and a strong presence of creativity, discussion, and interest in politics. But I also encountered a fear of economic collapse and a continued sense of turmoil, with strikes (mostly successful) continuing all over the country, a political struggle among political parties to share the cake of elections beforehand through alliances and deals, confrontation between competing sections within the Islamist spectrum (which has much more presence and popular support than the liberal and leftist camp), an increased visibility and activity of what in post-revolutionary jargon are called the fulul, or “leftovers” (literally, the dispersed units of a defeated army) of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party that was dissolved last spring, renewed confessional tensions, and last but not least a military rule tightening its grip over the country.

My revolutionary friends are without exception extremely frustrated about the situation. Some see the revolution in grave danger, others say that it has already failed, that it in fact failed on 11 February when the military took over from the Mubarak family. In different variations, they argue that the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) has proven itself as a faithful follower of Mubarak, intent on taking over power through the manipulation of the upcoming elections, if necessary by the way of spreading chaos and terror. Also the Islamists in their different colourings, who until the summer were very supportive of the military rule (hoping to strike a good power share deal), have turned critical of the SCAF, beginning to realise that the army is deceiving them just like Gamal Abdel Nasser did back in 1954 when after a period of cooptation, the Muslim Brotherhood was prohibited and brutally suppressed. But a lot of people (probably the majority) are still trustful in the army, believing what state television says and what public sector newspapers write. And most Egyptians are first of all busy with the economic situation, which is very difficult.

It was in this mixed atmosphere of an air of freedom and a sense of frustration and anxiety about the way things are evolving that I arrived in Alexandria three days ago, after spending a week in Cairo. Alexandria is one of the power bases of Salafis and the Muslim Brotherhood, and their posters and banners are visible all over the city, but not to the exclusion of others: posters of liberal or leftist parties, banners of new parties by the fulul, graffitis by the radical opposition and politicised football ultras.

The massacre at Maspiro