February, 2011

You are looking at posts that were written in the month of February in the year 2011.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jan | Mar » | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | ||||||

Pages

- About

- C L O S E R moves to….C L O S E R

- Contact Me

- Interventions – Forces that Bind or Divide

- ISIM Review via Closer

- Publications

- Research

Categories

- (Upcoming) Events (33)

- [Online] Publications (26)

- Activism (117)

- anthropology (113)

- Method (13)

- Arts & culture (88)

- Asides (2)

- Blind Horses (33)

- Blogosphere (192)

- Burgerschapserie 2010 (50)

- Citizenship Carnival (5)

- Dudok (1)

- Featured (5)

- Gender, Kinship & Marriage Issues (265)

- Gouda Issues (91)

- Guest authors (58)

- Headline (76)

- Important Publications (159)

- Internal Debates (275)

- International Terrorism (437)

- ISIM Leiden (5)

- ISIM Research II (4)

- ISIM/RU Research (171)

- Islam in European History (2)

- Islam in the Netherlands (219)

- Islamnews (56)

- islamophobia (59)

- Joy Category (56)

- Marriage (1)

- Misc. News (891)

- Morocco (70)

- Multiculti Issues (749)

- Murder on theo Van Gogh and related issues (326)

- My Research (118)

- Notes from the Field (82)

- Panoptic Surveillance (4)

- Public Islam (244)

- Religion Other (109)

- Religious and Political Radicalization (635)

- Religious Movements (54)

- Research International (55)

- Research Tools (3)

- Ritual and Religious Experience (58)

- Society & Politics in the Middle East (159)

- Some personal considerations (146)

- Deep in the woods… (18)

- Stadsdebat Rotterdam (3)

- State of Science (5)

- Twitwa (5)

- Uncategorized (74)

- Young Muslims (459)

- Youth culture (as a practice) (157)

General

- ‘In the name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful’

- – Lotfi Haddi –

- …Kelaat Mgouna…….Ait Ouarchdik…

- ::–}{Nour Al-Islam}{–::

- Al-islam.nl De ware godsdienst voor Allah is de Islam

- Allah Is In The House

- Almaas

- amanullah.org

- Amr Khaled Official Website

- An Islam start page and Islamic search engine – Musalman.com

- arabesque.web-log.nl

- As-Siraat.net

- assadaaka.tk

- Assembley for the Protection of Hijab

- Authentieke Kennis

- Azaytouna – Meknes Azaytouna

- berichten over allochtonen in nederland – web-log.nl

- Bladi.net : Le Portail de la diaspora marocaine

- Bnai Avraham

- BrechtjesBlogje

- Classical Values

- De islam

- DimaDima.nl / De ware godsdienst? bij allah is de islam

- emel – the muslim lifestyle magazine

- Ethnically Incorrect

- fernaci

- Free Muslim Coalition Against Terrorism

- Frontaal Naakt. Ongesluierde opinies, interviews & achtergronden

- Hedendaagse wetenswaardigheden…

- History News Network

- Homepage Al Nisa

- hoofddoek.tk – Een hoofddoek, je goed recht?

- IMRA: International Muslima Rights Association

- Informed Comment

- Insight to Religions

- Instapundit.com

- Interesting Times

- Intro van Abdullah Biesheuvel

- islaam

- Islam Ijtihad World Politics Religion Liberal Islam Muslim Quran Islam in America

- Islam Ijtihad World Politics Religion Liberal Islam Muslim Quran Islam in America

- Islam Website: Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic, Religion

- Islamforum

- Islamic Philosophy Online

- Islamica Magazine

- islamicate

- Islamophobia Watch

- Islamsevrouw.web-log.nl

- Islamwereld-alles wat je over de Islam wil weten…

- Jihad: War, Terrorism, and Peace in Islam

- JPilot Chat Room

- Madrid11.net

- Marocstart.nl – De marokkaanse startpagina!

- Maryams.Net – Muslim Women and their Islam

- Michel

- Modern Muslima.com

- Moslimjongeren Amsterdam

- Moslimjongeren.nl

- Muslim Peace Fellowship

- Muslim WakeUp! Sex & The Umma

- Muslimah Connection

- Muslims Against Terrorism (MAT)

- Mutma’inaa

- namira

- Otowi!

- Ramadan.NL

- Religion, World Religions, Comparative Religion – Just the facts on the world\’s religions.

- Ryan

- Sahabah

- Salafi Start Siden – The Salafi Start Page

- seifoullah.tk

- Sheikh Abd al Qadir Jilani Home Page

- Sidi Ahmed Ibn Mustafa Al Alawi Radhiya Allahu T’aala ‘Anhu (Islam, tasawuf – Sufism – Soufisme)

- Stichting Vangnet

- Storiesofmalika.web-log.nl

- Support Sanity – Israel / Palestine

- Tekenen van Allah\’s Bestaan op en in ons Lichaam

- Terrorism Unveiled

- The Coffee House | TPMCafe

- The Inter Faith Network for the UK

- The Ni’ma Foundation

- The Traveller’s Souk

- The \’Hofstad\’ terrorism trial – developments

- Thoughts & Readings

- Uitgeverij Momtazah | Helmond

- Un-veiled.net || Un-veiled Reflections

- Watan.nl

- Welkom bij Islamic webservices

- Welkom bij vangnet. De site voor islamitische jongeren!

- welkom moslim en niet moslims

- Yabiladi Maroc – Portail des Marocains dans le Monde

Dutch [Muslims] Blogs

- Hedendaagse wetenswaardigheden…

- Abdelhakim.nl

- Abdellah.nl

- Abdulwadud.web-log.nl

- Abou Jabir – web-log.nl

- Abu Bakker

- Abu Marwan Media Publikaties

- Acta Academica Tijdschrift voor Islam en Dialoog

- Ahamdoellilah – web-log.nl

- Ahlu Soennah – Abou Yunus

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Al Moudjahideen

- Al-Adzaan

- Al-Islaam: Bismilaahi Rahmaani Rahiem

- Alesha

- Alfeth.com

- Anoniempje.web-log.nl

- Ansaar at-Tawheed

- At-Tibyan Nederland

- beni-said.tk

- Blog van moemina3 – Skyrock.com

- bouchra

- CyberDjihad

- DE SCHRIJVENDE MOSLIMS

- DE VROLIJKE MOSLIM ;)

- Dewereldwachtopmij.web-log.nl

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Eali.web-log.nl

- Een genade voor de werelden

- Enige wapen tegen de Waarheid is de leugen…

- ErTaN

- ewa

- Ezel & Os v2

- Gizoh.tk [.::De Site Voor Jou::.]

- Grappige, wijze verhalen van Nasreddin Hodja. Turkse humor.

- Hanifa Lillah

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Het laatste nieuws lees je als eerst op Maroc-Media

- Homow Universalizzz

- Ibn al-Qayyim

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- Islam Blog – Juli 2007

- Islam in het Nieuws – web-log.nl

- Islam, een religie

- Islam, een religie

- Islamic Sisters – web-log.nl

- Islamiway’s Weblog

- Islamtawheed’s Blog

- Jihaad

- Jihad

- Journalista

- La Hawla Wa La Quwatta Illa Billah

- M O S L I M J O N G E R E N

- M.J.Ede – Moslimjongeren Ede

- Mahdi\’s Weblog | Vrijheid en het vrije woord | punt.nl: Je eigen gratis weblog, gratis fotoalbum, webmail, startpagina enz

- Maktab.nl (Zawaj – islamitische trouwsite)

- Marocdream.nl – Home

- Marokkaanse.web-log.nl

- Marokkanen Weblog

- Master Soul

- Miboon

- Miesjelle.web-log.nl

- Mijn Schatjes

- Moaz

- moeminway – web-log.nl

- Moslima_Y – web-log.nl

- mosta3inabilaah – web-log.nl

- Muhaajir in islamitisch Zuid-Oost Azië

- Mumin al-Bayda (English)

- Mustafa786.web-log.nl

- Oprecht – Poort tot de kennis

- Said.nl

- saifullah.nl – Jihad al-Haq begint hier!

- Salaam Aleikum

- Sayfoudien – web-log.nl

- soebhanAllah

- Soerah19.web-log.nl – web-log.nl

- Steun Palestina

- Stichting Moslimanetwerk

- Stories of Malika

- supermaroc

- Ummah Nieuws – web-log.nl

- Volkskrant Weblog — Alib Bondon

- Volkskrant Weblog — Moslima Journalista

- Vraag en antwoord…

- wat is Islam

- Wat is islam?

- Weblog – a la Maroc style

- website van Jamal

- Wij Blijven Hier

- Wij Blijven Hier

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- www.moslima.web-log.nl

- Yakini Time

- Youth Of Islam

- Youth Of Islam

- [fikra]

Non-Dutch Muslims Blogs

- Lanallah __Islamic BlogZine__

- This journey ends but only with The Beginning

- ‘the middle place’

- …Never Judge a Person By His or Her Blog…

- …under the tree…

- A Comment on PMUNA

- A Dervish’s Du`a’

- A Family in Baghdad

- A Garden of Children

- A Muslim Mother’s Thoughts / Islamic Parenting

- A Struggle in Uncertainty, Such is Life

- About Afghanistan

- adnan.org: good design, bad idea

- Afiyah

- Ahmeds World of Islam

- Al Musawwir

- Al-Musharaka

- Almiraya tBLOG – O, happy the soul that saw its own faults

- Almusawwir

- an open window

- Anak Alam

- aNaRcHo AkBaR

- Anthology

- AnthroGal’s World

- Arabian Passion

- ArRihla

- Articles Blog

- Asylum Seeker

- avari-nameh

- Baghdad Burning

- Being Noor Javed

- Bismillah

- bloggin’ muslimz.. Linking Muslim bloggers around the globe

- Blogging Islamic Perspective

- Chapati Mystery

- City of Brass – Principled pragmatism at the maghrib of one age, the fajr of another

- COUNTERCOLUMN: All Your Bias Are Belong to Us

- d i z z y l i m i t s . c o m >> muslim sisters united w e b r i n g

- Dar-al-Masnavi

- Day in the life of an American Muslim Woman

- Don’t Shoot!…

- eat-halal guy

- Eye on Gay Muslims

- Eye on Gay Muslims

- Figuring it all out for nearly one quarter of a century

- Free Alaa!

- Friends, Romans, Countrymen…. lend me 5 bux!

- From Peer to Peer ~ A Weblog about P2P File & Idea Sharing and More…

- Ghost of a flea

- Ginny’s Thoughts and Things

- God, Faith, and a Pen: The Official Blog of Dr. Hesham A. Hassaballa

- Golublog

- Green Data

- gulfreporter

- Hadeeth Blog

- Hadouta

- Hello from the land of the Pharaoh

- Hello From the land of the Pharaohs Egypt

- Hijabi Madness

- Hijabified

- HijabMan’s Blog

- Ihsan-net

- Inactivity

- Indigo Jo Blogs

- Iraq Blog Count

- Islam 4 Real

- Islamiblog

- Islamicly Locked

- Izzy Mo’s Blog

- Izzy Mo’s Blog

- Jaded Soul…….Unplugged…..

- Jeneva un-Kay-jed- My Bad Behavior Sanctuary

- K-A-L-E-I-D-O-S-C-O-P-E

- Lawrence of Cyberia

- Letter From Bahrain

- Life of an American Muslim SAHM whose dh is working in Iraq

- Manal and Alaa\’s bit bucket | free speech from the bletches

- Me Vs. MysElF

- Mental Mayhem

- Mere Islam

- Mind, Body, Soul : Blog

- Mohammad Ali Abtahi Webnevesht

- MoorishGirl

- Muslim Apple

- muslim blogs

- Muslims Under Progress…

- My heart speaks

- My Little Bubble

- My Thoughts

- Myself | Hossein Derakhshan’s weblog (English)

- neurotic Iraqi wife

- NINHAJABA

- Niqaabi Forever, Insha-Allah Blog with Islamic nasheeds and lectures from traditional Islamic scholars

- Niqabified: Irrelevant

- O Muhammad!

- Otowi!

- Pak Positive – Pakistani News for the Rest of Us

- Periphery

- Pictures in Baghdad

- PM’s World

- Positive Muslim News

- Procrastination

- Prophet Muhammad

- Queer Jihad

- Radical Muslim

- Raed in the Middle

- RAMBLING MONOLOGUES

- Rendering Islam

- Renegade Masjid

- Rooznegar, Sina Motallebi’s WebGard

- Sabbah’s Blog

- Salam Pax – The Baghdad Blog

- Saracen.nu

- Scarlet Thisbe

- Searching for Truth in a World of Mirrors

- Seeing the Dawn

- Seeker’s Digest

- Seekersdigest.org

- shut up you fat whiner!

- Simply Islam

- Sister Scorpion

- Sister Soljah

- Sister Surviving

- Slow Motion in Style

- Sunni Sister: Blahg Blahg Blahg

- Suzzy’s id is breaking loose…

- tell me a secret

- The Arab Street Files

- The Beirut Spring

- The Islamic Feminista

- The Land of Sad Oranges

- The Muslim Contrarian

- The Muslim Postcolonial

- The Progressive Muslims Union North America Debate

- The Rosetta Stone

- The Traceless Warrior

- The Wayfarer

- TheDesertTimes

- think halal: the muslim group weblog

- Thoughts & Readings

- Through Muslim Eyes

- Turkish Torque

- Uncertainty:Iman and Farid’s Iranian weblog

- UNMEDIA: principled pragmatism

- UNN – Usayd Network News

- Uzer.Aurjee?

- Various blogs by Muslims in the West. – Google Co-op

- washed away memories…

- Welcome to MythandCulture.com and to daily Arrows – Mythologist, Maggie Macary’s blog

- word gets around

- Writeous Sister

- Writersblot Home Page

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- www.Mas’ud’s blog

- \’Aqoul

- ~*choco-bean*~

General Islam Sites

- :: Islam Channel :: – Welcome to IslamChannel Official Website

- Ad3iyah(smeekbeden)

- Al-maktoum Islamic Centre Rotterdam

- Assalamoe Aleikoem Warhmatoe Allahi Wa Barakatuhoe.

- BouG.tk

- Dades Islam en Youngsterdam

- Haq Islam – One stop portal for Islam on the web!

- Hight School Teacher Muhammad al-Harbi\’s Case

- Ibn Taymiyah Pages

- Iskandri

- Islam

- Islam Always Tomorrow Yesterday Today

- Islam denounces terrorism.com

- Islam Home

- islam-internet.nl

- Islamic Artists Society

- Leicester~Muslims

- Mere Islam

- MuslimSpace.com | MuslimSpace.com, The Premiere Muslim Portal

- Safra Project

- Saleel.com

- Sparkly Water

- Statements Against Terror

- Understand Islam

- Welcome to Imaan UK website

Islamic Scholars

Social Sciences Scholars

- ‘ilm al-insaan: Talking About the Talk

- :: .. :: zerzaust :: .. ::

- After Sept. 11: Perspectives from the Social Sciences

- Andrea Ben Lassoued

- Anth 310 – Islam in the Modern World (Spring 2002)

- anthro:politico

- AnthroBase – Social and Cultural Anthropology – A searchable database of anthropological texts

- AnthroBlogs

- AnthroBoundaries

- Anthropologist Community

- anthropology blogs

- antropologi.info – Social and Cultural Anthropology in the News

- Arabist Jansen

- Between Secularization and Religionization Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

- Bin Gregory Productions

- Blog van het Blaise Pascal Instituut

- Boas Blog

- Causes of Conflict – Thoughts on Religion, Identity and the Middle East (David Hume)

- Cicilie among the Parisians

- Cognitive Anthropology

- Comunidade Imaginada

- Cosmic Variance

- Critical Muslims

- danah boyd

- Deep Thought

- Dienekes’ Anthropology Blog

- Digital Islam

- Erkan\’s field diary

- Ethno::log

- Evamaria\’s ramblings –

- Evan F. Kohlmann – International Terrorism Consultant

- Experimental Philosophy

- For the record

- Forum Fridinum [Religionresearch.org]

- Fragments weblog

- From an Anthropological Perspective

- Gregory Bateson

- Islam & Muslims in Europe *)

- Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic, Religion

- Islam, Muslims, and an Anthropologist

- Jeremy’s Weblog

- JourneyWoman

- Juan Cole – ‘Documents on Terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’

- Keywords

- Kijken naar de pers

- languagehat.com

- Left2Right

- Leiter Reports

- Levinas and multicultural society

- Links on Islam and Muslims

- log.squig.org

- Making Anthropology Public

- Martijn de Koning Research Pages / Onderzoekspaginas

- Material World

- MensenStreken

- Modern Mass Media, Religion and the Imagination of Communities

- Moroccan Politics and Perspectives

- Multicultural Netherlands

- My blog’s in Cambridge, but my heart is in Accra

- National Study of Youth and Religion

- Natures/Cultures

- Nomadic Thoughts

- On the Human

- Philip Greenspun’s Weblog:

- Photoethnography.com home page – a resource for photoethnographers

- Qahwa Sada

- RACIAL REALITY BLOG

- Religion Gateway – Academic Info

- Religion News Blog

- Religion Newswriters Association

- Religion Research

- rikcoolsaet.be – Rik Coolsaet – Homepage

- Rites [Religionresearch.org]

- Savage Minds: Notes and Queries in Anthropology – A Group Blog

- Somatosphere

- Space and Culture

- Strange Doctrines

- TayoBlog

- Teaching Anthropology

- The Angry Anthropologist

- The Gadflyer

- The Immanent Frame | Secularism, religion and the public sphere

- The Onion

- The Panda\’s Thumb

- TheAnthroGeek

- This Blog Sits at the

- This Blog Sits at the intersection of Anthropology & Economics

- verbal privilege

- Virtually Islamic: Research and News about Islam in the Digital Age

- Wanna be an Anthropologist

- Welcome to Framing Muslims – International Research Network

- Yahya Birt

Women's Blogs / Sites

- * DURRA * Danielle Durst Britt

- -Fear Allah as He should be Feared-

- a literary silhouette

- a literary silhouette

- A Thought in the Kingdom of Lunacy

- AlMaas – Diamant

- altmuslimah.com – exploring both sides of the gender divide

- Assalaam oe allaikoum Nour al Islam

- Atralnada (Morning Dew)

- ayla\’s perspective shifts

- Beautiful Amygdala

- bouchra

- Boulevard of Broken Dreams

- Chadia17

- Claiming Equal Citizenship

- Dervish

- Fantasy web-log – web-log.nl

- Farah\’s Sowaleef

- Green Tea

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Hilsen Fra …

- Islamucation

- kaleidomuslima: fragments of my life

- Laila Lalami

- Marhaban.web-log.nl – web-log.nl

- Moslima_Y – web-log.nl

- Muslim-Refusenik The official website of Irshad Manji

- Myrtus

- Noor al-Islaam – web-log.nl

- Oh You Who Believe…

- Raising Yousuf: a diary of a mother under occupation

- SAFspace

- Salika Sufisticate

- Saloua.nl

- Saudi Eve

- SOUL, HEART, MIND, AND BODY…

- Spirit21 – Shelina Zahra Janmohamed

- Sweep the Sunshine | the mundane is the edge of glory

- Taslima Nasrin

- The Color of Rain

- The Muslimah

- Thoughts Of A Traveller

- Volkskrant Weblog — Islam, een goed geloof

- Weblog Raja Felgata | Koffie Verkeerd – The Battle | punt.nl: Je eigen gratis weblog, gratis fotoalbum, webmail, startpagina enz

- Weblog Raja Felgata | WRF

- Writing is Busy Idleness

- www.moslima.web-log.nl

- Zeitgeistgirl

- Zusters in Islam

- ~:: MARYAM ::~ Tasawwuf Blog

Ritueel en religieuze beleving Nederland

- – Alfeth.com – NL

- :: Al Basair ::

- Abu Marwan Media Publikaties

- Ahlalbait Jongeren

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- Al-Amien… De Betrouwbare – Home

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Ummah

- Al-Wasatiyyah.com – Home

- Anwaar al-Islaam

- anwaaralislaam.tk

- Aqiedah’s Weblog

- Arabische Lessen – Home

- Arabische Lessen – Home

- Arrayaan.net

- At-taqwa.nl

- Begrijp Islam

- Bismillaah – deboodschap.com

- Citaten van de Salaf

- Dar al-Tarjama WebSite

- Dawah-online.com

- de koraan

- de koraan

- De Koran . net – Het Islaamitische Fundament op het Net – Home

- De Leidraad, een leidraad voor je leven

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Dien~oel~Islaam

- Faadi Community

- Ghimaar

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- hayya~ala~assalaah!

- Ibn al-Qayyim

- IMAM-MALIK-Alles over Islam

- IQRA ROOM – Koran studie groep

- Islaam voor iedereen

- Islaam voor iedereen

- Islaam: Terugkeer naar het Boek (Qor-aan) en de Soennah volgens het begrip van de Vrome Voorgangers… – Home

- Islaam: Terugkeer naar het Boek (Qor-aan) en de Soennah volgens het begrip van de Vrome Voorgangers… – Home

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- islam :: messageboard

- Islam City NL, Islam en meer

- Islam, een religie

- Islamia.nl – Islamic Shop – Islamitische Winkel

- Islamitische kleding

- Islamitische kleding

- Islamitische smeekbedes

- islamtoday

- islamvoorjou – Informatie over Islam, Koran en Soenah

- kebdani.tk

- KoranOnline.NL

- Lees de Koran – Een Openbaring voor de Mensheid

- Lifemakers NL

- Marocstart.nl | Islam & Koran Startpagina

- Miesbahoel Islam Zwolle

- Mocrodream Forums

- Moslims in Almere

- Moslims online jong en vernieuwend

- Nihedmoslima

- Oprecht – Poort tot de kennis

- Quraan.nl :: quran koran kuran koeran quran-voice alquran :: Luister online naar de Quraan

- Quraan.nl online quraan recitaties :: Koran quran islam allah mohammed god al-islam moslim

- Selefie Nederland

- Stichting Al Hoeda Wa Noer

- Stichting Al Islah

- StION Stichting Islamitische Organisatie Nederland – Ahlus Sunnat Wal Djama\’ah

- Sunni Publicaties

- Sunni.nl – Home

- Teksten van Aboe Ismaiel

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Terug Naar De Dien – Home

- Uw Keuze

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.al-thabaat.com

- www.hijaab.com

- www.uwkeuze.net

- Youth Of Islam

- Zegswijzen van de Wijzen

- \’\’ Leid ons op het rechte pad het pad degenen aan wie Gij gunsten hebt geschonken\’\’

Muslim News

Moslims & Maatschappij

Arts & Culture

- : : SamiYusuf.com : : Copyright Awakening 2006 : :

- amir normandi, photographer – bio

- Ani – SINGING FOR THE SOUL OF ISLAM – HOME

- ARTEEAST.ORG

- AZIZ

- Enter into The Home Website Of Mecca2Medina

- Kalima Translation – Reviving Translation in the Arab world

- lemonaa.tk

- MWNF – Museum With No Frontiers – Discover Islamic Art

- Nader Sadek

Misc.

'Fundamentalism'

Islam & commerce

2

Morocco

[Online] Publications

- ACVZ :: | Preliminary Studies | About marriage: choosing a spouse and the issue of forced marriages among Maroccans, Turks and Hindostani in the Netherlands

- ACVZ :: | Voorstudies | Over het huwelijk gesproken: partnerkeuze en gedwongen huwelijken onder Marokkaanse, Turkse en Hindostaanse Nederlanders

- Kennislink – ‘Dit is geen poep wat ik praat’

- Kennislink – Nederlandse moslims

Religious Movements

- :: Al Basair ::

- :: al Haqq :: de waarheid van de Islam ::

- ::Kalamullah.Com::

- Ahloelhadieth.com

- Ahlul Hadeeth

- al-Madinah (Medina) The City of Prophecy ; Islamic University of Madinah (Medina), Life in Madinah (Medina), Saudi Arabia

- American Students in Madinah

- Aqiedah’s Weblog

- Dar al-Tarjama WebSite

- Faith Over Fear – Feiz Muhammad

- Instituut voor Opvoeding & Educatie

- IslaamLive Mail

- IslaamLive Mail

- islamtoday

- Moderate Muslims Refuted

- Rise And Fall Of Salafi Movement in the US by Umar Lee

- Selefie Dawah Nederland

- Selefie Nederland

- Selefienederland

- Stichting Al Hoeda Wa Noer

- Teksten van Aboe Ismaiel

- www.ahloelhadieth.com

- www.BenAyad.be – Islam en Actua

- Youth Of Islam

Closing the week 8 – A need to read list of the uprisings in the Middle East

Posted on February 27th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Blogosphere, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Most popular on Closer this week:

- De Marokkaanse Uitzondering? door Nina ter Laan

- Tunisia: From Paradise to Hell and Back? by Miriam Gazzah

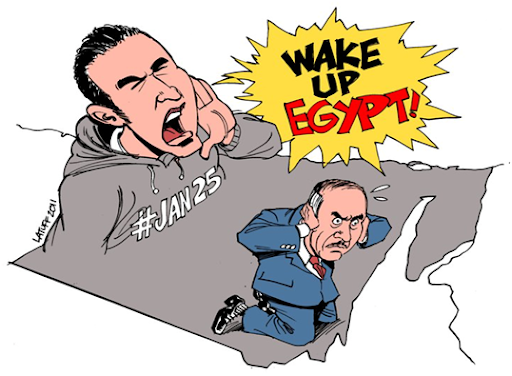

- Egypts Revolution 2.0 – The Facebook Factor by Linda Herrera

Previous updates: : Tunisia Uprising I – Tunisia Uprising II – Tunisia / Egypt Uprising Essential Reading I – The Egypt Revolution. See also the section Society and Politics in the Middle East (Dutch and English guest contributions).

- If you want to stay updated and did not subscribe yet, you can do so HERE

- You can follow me on Twitter: Martijn5155

Essential readings again

Religioscope: Egypt: Islam in the insurrection

“Arab anger” in Egypt was no more Islamist than it had been in Tunisia a few weeks earlier. Islam was an ingredient, but no more than that. The various religious groups played a role that was politically very conservative. Few supported the protest movement, some were obliged to show some solidarity, many were frankly opposed. And this went for Copts as much as Muslims.

This revolt is not just against the tyrants but also against the ‘system’ and, as I will explain below, against how the “civilized” West feels entitled to manage the “civilizable” East. To understand this process, we need to make sense of how Arabs, Muslims (and in this case the Middle East) has been conceptualized. As we shall see, anthropology since the 1970s has had lots to say about it and, as some may be surprised to come to know, has directly – but even more so indirectly (nearly subconsciously) -deeply influenced political scientists and then politicians and policies.

Egypt and the global economic order – Opinion – Al Jazeera English

The strikers were responding to the fast-track imposition of neo-liberal economic policies by a cabinet led by Ahmed Nazif, the then prime minister who relentlessly implemented the demands of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). These measures included the privatisation of public factories, the liberalisation of markets, decreasing tariffs and import taxes and the introduction of subsidies for agri-businesses in place of those for small farmers with the aim of increasing agricultural exports.

‘Volcano of Rage’ by Max Rodenbeck | The New York Review of Books

Despite wide variations in the nominal forms of government in all these countries, as well as contrasting levels of wealth and education and urbanization, the pattern and shape of the unrest, and the grievances that provoked it, looked everywhere much the same. Arab rulers had grown too isolated, too inflated with pretense and hypocrisy, and too complacently confident in the power of their police. Their overwhelmingly youthful populations suffered perpetual humiliation at the hands of government officials, faced dim work prospects, and had little means of influencing politics. They felt, in the famous words of the Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous, that they were “sentenced to hope.” More sophisticated and exposed to the world than the generation that ruled them, they had lost faith in the whole patriarchal construct that seemed to hem in their lives.

The Revolution Against Neoliberalism

To describe blatant exploitation of the political system for personal gain as corruption misses the forest for the trees. Such exploitation is surely an outrage against Egyptian citizens, but calling it corruption suggests that the problem amounts to aberrant behavior from a system that would otherwise function smoothly. If this were the case then the crimes of the Mubarak regime could be attributed simply to bad character: change the people and the problems go away. But the real problem with the regime was not necessarily that high-ranking members of the government were thieves in an ordinary sense. They did not necessarily steal directly from the treasury. Rather they were enriched through a conflation of politics and business under the guise of privatization. This was less a violation of the system than business as usual. Mubarak’s Egypt, in a nutshell, was a quintessential neoliberal state.

Women of the revolution – Features – Al Jazeera English

Egyptian women, just like men, took up the call to ‘hope’. Here they describe the spirit of Tahrir – the camaraderie and equality they experienced – and their hope that the model of democracy established there will be carried forward as Egyptians shape a new political and social landscape.

The Architects of the Egyptian Revolution | The Nation

While a new democratic regime might ensure civil and political rights within the framework of a liberal democracy, it is unclear whether the reforms necessary for addressing economic injustice and inequality can be implemented within this framework. Since the 1970s, the Egyptian economy has been increasingly subject to neoliberal economic reforms by the World Bank, the IMF and USAID at the behest of the United States government. Egyptian elites have been beneficiaries of, and partners in, these American-driven reforms. Will this sector of Egyptian society accommodate the demands of the poor, the unemployed and the workers who have so far been equal partners in their struggle against political corruption and autocracy? Will the protestors in Tahrir Square continue to fight for economic justice even as they gain political and civil rights in the months to come?

A private estate called Egypt | Salwa Ismail | Comment is free | The Guardian

There is a lot more behind Hosni Mubarak digging in his heels and setting his thugs on the peaceful protests in Cairo’s Tahrir Square than pure politics. This is also about money. Mubarak and the clique surrounding him have long treated Egypt as their fiefdom and its resources as spoils to be divided among them.

The Struggle to Define the Egyptian Revolution | The Middle East Channel

It is not that the old regime still remains (though it does; the junta and the cabinet are both still staffed by pre-revolutionary appointees and only vague hints of a cabinet reshuffle have been floated). It is clear that real change of some kind will take place. But the shape of the transition has not yet been defined. A more democratic, pluralistic, participatory, public-spirited, and responsive political system is a real possibility. But so is a kinder, gentler, presidentially-dominated, liberalized authoritarianism. In this post, I will discuss the state of play in Egypt; in future writings I hope to explore the implications for other regimes in the region.

Guernica / Nomi Prins: The Egyptian Uprising Is a Direct Response to Ruthless Global Capitalism

The revolution in Egypt is as much a rebellion against the painful deterioration of economic conditions as it is about opposing a dictator, though they are linked. That’s why President Hosni Mubarak’s announcement that he intends to stick around until September was met with an outpouring of rage.

Arab and American revolutions in history « The Immanent Frame

In this post, I will attempt to clarify my position by offering a historical view of how our celebration of what we now call the American Revolution requires us to support the maturation of what are now “mass protests” into the Arab Revolutions. The primary role in that process must be that of Arabs themselves, with each society acting in its own context. But the role of citizens of the United States is a matter of individual personal responsibility, because it is immediately connected to our attitudes and behavior. To the question posed in Thomas Farr’s title—“Where lies wisdom, where folly?”—I say that the universal measure is always the Golden Rule: Do unto others what you would have them do unto you. My strong opposition to the IRFA reflects my opposition to the United States’ failure to uphold the Golden Rule in its foreign policies. If the United States wishes to preach to others the imperative of protecting human rights, it must first apply that injunction to itself. My point is not that civil rights are violated in the United States, though there is sufficient reason for concern on that count; rather, the point is that domestic respect for the civil rights of citizens is not the same as the protection of human rights for all human beings equally, by virtue of their humanity and not their status as citizens. The United States does not have the moral standing and political legitimacy to uphold human rights anywhere in the world, unless it is willing to be judged by the same standards that it claims to apply to others.

Islam and the compulsion of the political « The Immanent Frame

My theoretical point concerns the compulsion of the political in discussing Islam more generally. What are the foreclosures of understanding Islam solely in political terms? Whether in Turkey, Egypt, or elsewhere, why does the analysis and assessment of Islam privilege, presuppose, and entail political argument? As Talal Asad has persuasively argued, the politicization of religion is a definitive feature of ‘the secular.’ From the secular perspective Asad describes, the supposedly fraught relationship between religion and politics (which secularism posits as necessarily problematic) exhausts the interest and importance of religion itself. My final point follows directly from this observation—the compulsion to discuss and comprehend Islam in solely political terms is a political fact in its own right. The compulsion of the political is a self-fulfilling prophecy, one that compels Muslims to account for themselves and their faith in strictly political language, because it assumes that Islam is inherently political. Rather than continue to ask how Islam relates to politics—rather than repeat the compulsion—I suggest that we begin to interrogate the difficulty of thinking of Islam non-politically. It is this question that urgently demands attention and address. The goal of this interrogation should not be to demonstrate, in antithetical fashion, that Islam is essentially non-political—to do so would be to remain within the binary logic that essentializes both Islam and politics. Rather, we should endeavor to speak truth to the powers that insist that Islam is necessarily, monolithically political, and that thereby render Islam itself monolithic and homogeneous.

The power of a new political imagination « The Immanent Frame

However, another wall is still standing: the widely perceived threat of the “Islamic state.” Observers in the U.S., Europe, and the Middle East worry that these revolutions could morph into “religious revolutions” and lead to “Islamic states.” They invariably ask: “What is the role of the Islamists?” “Will they take over the state?” These fears are based on a misunderstanding of the nature of the popular mobilizations in Tunisia and Egypt, of the relation between Islam and politics in the modern Arab Middle East, and on a narrow political imagination. These observers believe that Tunisia and Egypt can be one of only two things: a “secular” dictatorship or an Islamic republic on the Iranian model. This paradigm is plain wrong.

A Muslim revolution in Egypt « The Immanent Frame

Underlying the continuing utility of this trope is the presumption that Muslims as political actors face a stark choice. Secular, liberal democracy vs. Islamist, religious theocracy. There is no middle ground. It is for this reason that the AKP in Turkey continues to be called “mildly Islamist” by The Economist and other publications, while the GOP (which in many ways is far more Christian than the AKP is Islamic) needs no such qualifier. It is this same trope that Hosni Mubarak has used to great effect over the last three decades to justify his repressive regime to his friends in the West. In fact, when James Clapper, the Director of National intelligence, recently tried to make the case to Congress that the Muslim Brotherhood had disavowed violence for participation in democratic politics, he could find no other language to describe it except to call the group “largely secular”! Although he was immediately assailed by folks from the left and the right for this supposed faux pas, he was only giving voice to the internal contradiction built into the dualistic trope through which the West continues to miscomprehend both Islam and Muslims. Recent events in Egypt and elsewhere are unequivocal signs that Muslims will no longer be held hostage to this artificial and corrupt dualism. They are democratic and Muslim. Deal with it.

Five reasons why Arab regimes are falling – CSMonitor.com

Public protests in Egypt are not about minor changes or grievances. President Hosni Mubarak’s regime faces a deep process of legitimacy erosion – the same pattern of legitimacy erosion that exists across much of the Arab region. This erosion won’t simply go away with more protests or new governments, and it will be with us in the years to come. Understanding the larger societal and demographic factors eroding these regimes is vital to understanding the unrest in the Middle East and how the Arab world can move forward.

Egypt’s uprising: different media ensembles at different stages « media/anthropology

In the contemporary era when political actors (rulers, politicians, activists, journalists, citizens, etc.) have access to multiple media, when analysing a struggle it is crucial that we establish which media ensembles – or media mixes – came to the fore at which particular stages of the conflict. Although it is still early days to reconstruct the Egyptian uprising, it is already clear that indeed different stages have seen different constellations of media-related activity in Cairo and other sites of conflict. To illustrate this point, let us retrace the steps of the still unresolved dispute by means of a timeline drawn from Al Jazeera, the BBC, Wikipedia, and other sources.

Benhabib | Public Sphere Forum

What no commentator foresaw is the emergence of a movement of mass democratic resistance that is thoroughly modern in its understanding of politics and sometimes “pious,” but not fanatical – an important distinction that is permanently blurred over. Just as followers of Martin Luther King were educated in the black churches in the American South and gained their spiritual strength from these communities, so the crowds in Tunis, Egypt and elsewhere draw upon Islamic traditions of Shahada – being a martyr and witness of God at once! There is no necessary incompatibility between the religious faith of many who participated in these movements and their modern aspirations!

Chrystia Freeland | Analysis & Opinion | Reuters.com

They are being called the Facebook revolutions, but a better term for the uprisings sweeping through the Middle East might be the Groupon effect. That is because one of the most powerful consequences satellite television and the Internet have had for the protest movements is to help them overcome the problem of collective action, in the same way that Groupon has harnessed the Web for retailers.

The End of the Arab Dream – By James Traub | Foreign Policy

If Muammar al-Qaddafi falls, as seems increasingly likely, he will land with the rending crash of an immense, rigid object, like the statue of Saddam Hussein pulled down in Baghdad’s Firdos Square. This is not because, despite his own delusions, Qaddafi mattered to the world remotely as much as Saddam did. Rather, it’s because the Jamahiriya, or stateless society, he fostered in Libya constitutes the last of the revolutionary fantasies with which Arab leaders have mesmerized their citizens and justified their ruthless acts of repression since the establishment of the modern Arab world in the years after World War II.

Egypt

“I Saw God in Tahrir” « American Anthropological Association

while the Brotherhood will certainly play a formative role in post-revolutionary politics and governance in Egypt, it does not have a monopoly on Islamic discourse in the country.

Other important Islamic actors are Islamic televangelists, the most famous being Amr Khaled.

Jihadis Debate Egypt (3) — jihadica

What I find most interesting in the communiqué is the emphasis on the post-revolutionary phase and the character of the new regime. This is different from Abu Mundhir al-Shanqiti’s fatwa (see my earlier post) and Abu Sa’d al-Amili’s epistle (see below). The Mas’adat al-Mujahidin communiqué stresses the need for “preserving the fruits of your jihad”, not allowing the opportunists “to steal it”: “Any other rule but Islam will not protect you”. Furthermore, it states that “there is no excuse to delay the efforts to achieve this hope.” Failing to do so, it warns, the Egyptian brothers will face a new regime that “will be worse” and many times more corrupt than Mubarak’s. The international dimension of the post-revolutionary phase is not ignored: “you have not only broken your own shackles, but you will liberate the peoples of the other Arab countries from the tyrants of corruption and oppression. The hopes of the Islamic nations depend upon you.” The communiqué ends with a call to Egyptian clerics to forcefully declare their support for the Uprising and remove any doubt about its religious legitimacy.

Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood faces prospect of democracy amid internal discord

With President Hosni Mubarak gone, the Muslim Brotherhood is finding the prospect of democracy here a mixed blessing.

hawgblawg: More on Ahmed Basiony, Martyr of the Egyptian Revolution

AfricanColours has published Ahmed Basiony’s impressive Artistic C.V. with a few photos of some of his artwork. Basiony (or Bassiouni) died on January 28 at Tahrir, at the hands of Egypt’s security forces. Above is a sample of his artwork.

Muslim television preacher returns to Egypt – CNN Belief Blog – CNN.com Blogs

As Egyptians returned to Tahrir Square to push for the realization of more political demands, one of the world’s most influential Muslim television preachers delivered his first address in Egypt since President Hosni Mubarak left office.

“I don’t have a stronger message than this: Kill yourself working for Egypt,” Amr Khaled told a crowd of thousands.

Libya

On Libya: Why We Need Nuance « ZERO ANTHROPOLOGY

WARNING: Contains satire, mockery and travesty. Suitable for mature audiences only.

Reported events in Libya are very intriguing, to some extent. While one hopes that the following statements do not go too far over the top, we might say that unconfirmed allegations of loss of life may give one reason for pause. It is possible that some of us may entertain certain misgivings about the multifaceted and complex comments offered by the Libyan leader. While some may wish to argue that Col. Gaddafi is a “dictator,” a less tendentious characterization should suggest itself as the situation is neither black nor white, but grey.

It is important that the tone of discussion be kept serious, civil, and reasoned.

The Ancient Past of Libya and Libyans

Ancient Libya was defined as the rather large area in North Africa west of Egypt and west of the Nile River Valley, an area belonging to the afterlife.

Libya: Past and future? – Opinion – Al Jazeera English

Many believed that Colonel Gaddafi’s regime in Libya would withstand the gale of change sweeping the Arab world because of its reputation for brutality which had fragmented the six million-strong population over the past 42 years.

Its likely disappearance now, after a few days of protest by unarmed demonstrators is all-the-more surprising because it has systematically destroyed even the slightest pretence of dissidence and has atomised Libyan society to ensure that no organisation – formal or spontaneous – could ever consolidate sufficiently to oppose it.

Libya repression and protest: Long repressed, Libyans take a brave step toward freedom – latimes.com

Libyans thus had little opportunity to assemble components of civil society. Political associations, human rights organizations, independent professional associations or trade unions were all strictly proscribed, and organized opposition to the “ideology of the 1969 revolution” was punishable by death. On my first visit to Libya in 2005, the specially selected “civil society representatives” permitted to talk with us, and even government officials we met, displayed anxiety about expressing any opinions outside their sanctioned talking points. They literally recited chapter and verse of the Green Book, Kadafi’s small manuscript on governance. The performance was unmatched by anything I had seen in Syria and Iraq.

While dark humour has never been a strong quality in Libyans, there was one moment at Tripoli airport yesterday which proved it does exist. An incoming passenger from a Libyan Arab Airlines flight at the front of an immigration queue bellowed out: “And long life to our great leader Muammar Gaddafi.” Then he burst into laughter – and the immigration officers did the same.

Exclusive Update from Benghazi: Inside Information on the Opposition Movement

This morning, I spoke to Mohammed Fannoush, an active dissident in Benghazi, who informed me that the liberated cities, in both the East and West, have come together and organized a committee which will serve as a collective organ from which they will continue to unwaveringly fight for the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi. Fannoush has been put in charge of communication and urged me and other Arab-Americans to be active in clarifying the situation of the anti-Gaddafi movement in Libya as being nationalist, as opposed to Gaddafi’s manipulative accusations of a radical Islamist, specifically Al-Qaeda, led opposition. This movement is one based in a struggle for freedom, social justice, civil rights, education, health, and human dignity, of which Gaddafi has deprived them for over 40 years.

tabsir.net » Gaddafi: odd and daffy to the end

The irony is that as much as Gaddafi is hated in the West, thus far little has been done to stop him. Perhaps Berlusconi will send a plane to spirit his friend out, but Gaddafi seems crazy enough to try and hold on to power no matter how many people are killed. The U.N. Security Council is meeting, but thus far only words have been hurled in Gaddafi’s direction. Swiss banks have frozen his assets. The oil fields have been taken over by protesters, supported by the army. The days of Colonel Gaddafi are nearing an end, but probably not before many more lives are taken.

Is Gaddafi just defending his own interests? Is there something more than just a struggle to maintain power?

To understand this we have to move our attention from Libya to a European country: Italy, the gate to Europe for thousands of illegal migrants from Africa and in particular Libya.

More to the point in the present context, Libyans have almost unanimously rejected the prospects of foreign intervention during or after their revolution, on the grounds that its objective will be to keep Libya and its oil safe from the Libyan people. Should they succeed in safeguarding their sovereignty, this may prove their best insurance against a “democratic transition” Iraqi-style.

Bahrain

Bahrain Then and Now: Reflections on the Future of the Arab Monarchies

But today, as authoritarian “republics” across the Arab world tremble and sometimes tumble, little Bahrain is the first kingdom to be challenged by the wave of popular democratic protest. It is bad enough when it has to cancel the Formula One racing event. But you know matters are getting really serious when the king’s police open fire on peaceful demonstrators, prompting protesters to escalate their demands and call for the abolition of the monarchy itself. That hasn’t happened before. Does the present king—and especially his entourage—still possess sufficient legitimacy to face the present crisis?

Notes from the Bahraini Field [Update 2]

The following constitutes a series of email reports (to be updated regularly) from Jadaliyya affiliates in Manama. They will be updated in the next few days to reflect the latest developments in Bahrain. For some important differences between Bahrain and Egypt/Tunisia, see our Jadaliyya article entitled “Is Bahrain Next.”

The Canadian Press: Protest marches fill Bahrain capital as pressure mounts on rulers

MANAMA, Bahrain — Thousands of protesters streamed through Bahrain’s diplomatic area and other sites Sunday, chanting against the country’s king and rejecting his appeals for talks to end the tiny Gulf nation’s nearly two-week-old crisis.

Misc.

Saba Mahmood: Democracy is not enough – Anthropologists on the Arab revolution part II

While the revolutions in Northern Africa and the Middle East are spreading and the Libyan people managed to get rid of another dictator, anthropologists continue to comment the recent events. Here is a short overview.

From fear to fury: how the Arab world found its voice | Music | Music | The Observer

Before the revolution, Egypt’s metal heads lived in fear of arrest. Bullet belts, Iron Maiden T-shirts, horn gestures and headbanging were closet pastimes for foolhardy freaks. Bands such as Bliss, Wyvern, Hate Suffocation, Scarab, Brutus and Massive Scar Era rocked their fans like the priests of a persecuted sect who lived in constant wariness of the ghastly Mukhabarat, Mubarak’s secret police.

Soundtrack to the Arab revolutions | Music | The Observer

Rapper El Général helped spark the uprising in Tunisia, and in Egypt musicians bravely played their part in their nation’s transformation with these impassioned and incendiary tracks

Egypt; The Unexpected (and Unfinished) Revolution « Fifp

I wanted to understand why we did not see in Egypt the kind of collective action we saw in Iran. As an insight as to my line of thought, here’s a section of my conclusion:

“The key factors in explaining the absence of collective action in the Egyptian context and the absence of an Egyptian protest movement lies in an appreciation of the difference trajectory that the country has and continues to develop in, as compared to Iran. Egyptian revolutionary zeal was at its prime under the British occupation and took on an anti-imperialist, nationalist character and is yet to embrace an ideology in the modern context enabling it to unite under a general banner in defiance to the country’s existing authoritarian regime. The Egyptians, unlike the Iranians, lack a history of a united collective successful movement. In addition, the Egyptian state has been much more consistent in its approach towards the masses than its Iranian counterpart. This has meant a long history of repression, blocking of avenues of participation and the undermining of Islam as a revolutionary force.”

The Syrian Style of Repression: Thugs and Lectures – TIME

It was a formidable show of force, clearly meant to intimidate. The security personnel easily outnumbered the small crowd of less than 200 that was prevented — by a human barricade of uniformed men — from gathering anywhere near the embassy to denounce violence against anti-government protesters in Libya. Instead, the demonstration moved to a nearby park some 100 meters away.

Lebanese youth demonstrated against the government, calling for an end to sectarian politics in Lebanon. The protesters marched from the Mar Mikhael church intersection to the Adliyeh area of Beirut on Sunday, called for a secular state. Initial reports indicate that as many as 4,000 protesters took part despite the poor wether conditions.

The docile, supine, unregenerative, cringing Arabs of Orientalism have transformed themselves into fighters for the freedom, liberty and dignity which we Westerners have always assumed it was our unique role to play in the world. One after another, our satraps are falling, and the people we paid them to control are making their own history – our right to meddle in their affairs (which we will, of course, continue to exercise) has been diminished for ever.

After Iraq’s Day of Rage, a Crackdown on Intellectuals

BAGHDAD – Iraqi security forces detained about 300 people, including prominent journalists, artists and lawyers who took part in nationwide demonstrations Friday, in what some of them described as an operation to intimidate Baghdad intellectuals who hold sway over popular opinion.

Obama Is Helping Iran – By Flynt and Hillary Mann Leverett | Foreign Policy

We take billionaire financier George Soros up on the bet he proffered to CNN’s Fareed Zakaria this week that “the Iranian regime will not be there in a year’s time.” In fact, we want to up the ante and wager that not only will the Islamic Republic still be Iran’s government in a year’s time, but that a year from now, the balance of influence and power in the Middle East will be tilted more decisively in Iran’s favor than it ever has been.

Agency and Its Discontents: Between Al Saud’s Paternalism and the Awakening of Saudi Youth

Public life has been calmer than usual in Saudi Arabia for the last month. Invigorated by the people’s revolutionary movements in Tunisia and Egypt and anxious about the increasing violence in Libya, Bahrain and Yemen, Saudis have been following the news obsessively, perhaps for the first time in a decade. Salon talk has also shifted to serious discussions of the less than ideal role the Saudi government has played in the historic regional developments we are witnessing today. Within these discussions, predictions of what will happen next in Saudi Arabia vary, but all agree that the future course of events rests on what King Abdullah will do upon his return. In this context, two days ago, dubbed “Bright Wednesday” by Saudi media, marked a turning point in shaping the course that local movements for change will adopt.

Sacrifice and the Ripple Effect of Tunisian Self-immolation « American Anthropological Association

The years to come will certainly shed more light on the different local activities around Tunisia that served to turn Bouazizi’s act into a catalyst for national revolt rather than a localized incident. In the wake of Tunisia’s success, there were several cases of self-immolation across the Arab world, mainly in places like Egypt and Algeria. It is important to understand the Bouazizi sacrifice and the copycat cases, and to then reflect on the role of sacrifice to bring about change, the use of sacrifice in Egypt in particular, and why the other self-immolation cases did not engender the same reactions.

Dutch

Quote van de Dag: Elke islam-democratie is fake – GeenCommentaar

Volgens Wilders gaan islam en democratie niet samen, maar democratie en moslims wel. Maar dan wel moslims die soort van de islam niet meer aanhangen.

PVV, islam en vrijheid: De moslim als dhimmi | www.dagelijksestandaard.nl

Concluderend: de PVV, die met de aanval op de multikul opkwam voor de individuele vrijheid van de Nederlander, beschadigt met haar voorgestelde beleid de individuele vrijheid en daarmee verantwoordelijkheid van allochtonen en moslims. Is ze de partij van de individuele vrijheid van alle Nederlanders, of alleen van de communale vrijheid van autochtonen? Wordt het multikul, monokul, of liberalisme?

Onbedwelmd slachten III, de islamitische dhabihah « Kandigols Weblog

Het is me al vaker opgevallen dat vooral degenen met uitgesproken standpunten over moslims en islam, nooit met moslims verkeren, of zelfs maar eens in een islamitische slagerij komen. Men baseert zijn hele sociologische totaaltheorie op achterhaalde noties, halve verzinsels en angstvisioenen.

Henk Vroom schrijft beleidsadvies ‘Dialogue with Islam’ : Nieuwemoskee

Het research rapport Dialogue with Islam: Facing the Challenge of Muslim Integration in France, Netherlands, Germany bevat beleidsadviezen voor overheidsbeleid ten aanzien van moslims en moskee-organisaties. Het is geschreven op verzoek van het Centre for European Studies, het wetenschappelijk bureau van de Europese Volkspartij, te Brussel.

Mirjam Shatanawi, Islam in beeld. Kunst en cultuur van moslims wereldwijd | Eutopia Institute

Mirjam Shatanawi stelt heel wat pregnante vragen bij termen als ‘islamitisch’; ‘kunst’ en ‘cultuur’ en bij het verzamelen en exposeren ervan, zonder daar altijd duidelijke antwoorden op te kunnen of te willen geven. Het belangrijkste is dat de vragen een nieuwe discussieruimte openen, een aantal vastgeroeste betekenissen weer vlot maken, en doen nadenken over bewuste en onbewuste beeldvorming en over de ideologieën die onze manier van kijken bepalen. Wie dit soort studies ernstig neemt, kan het woord ‘islam’ niet meer gebruiken op de normatieve en eenduidige manier waarop dat op dit ogenblik in het Nederlandse islamdebat nog steeds gebeurt.

Volhoudbaar: Gekke koeien. Het moet niet dommer worden.

ChristenUnie is bondgenoot geworden in de strijd tegen de islam en door voor een verbod op de sharia te pleiten feitelijk nu ook tegen de moslims zelf.

Het is inmiddels nogal flauw om nog een spook door Europa te laten waren, maar de sharia zou je anders met een gerust hart een dergelijke verschijningsvorm toe kunnen dichten. Het is in ieder geval een mysterieus ding, die sharia, net zo geschikt voor een gesprek als het weer. Je hoeft er geen verstand van te hebben om er toch over mee te kunnen praten. Het verschil is slechts dat je het weer aan den lijve voelt en dus, ook als je geen meteoroloog bent, op zijn minst op enige eigen waarneming kunt bogen, terwijl het aardige van de sharia is dat het echt een Gespenst is, om de term van Marx en Engels maar aan te halen: werkelijk zien doe je het ding niet, maar je kunt er wel lekker voor griezelen.

Rouvoet en Kuiper: Anti-sharia-bepaling geeft duidelijkheid – Opinie – TROUW

opinie Een preambule in de Grondwet snijdt ook het pad af van populisten die de vrijheden van moslims teniet willen doen. Vrijheid en waardigheid worden niet per stemming bepaald.

Jadaliyya Interview with Ali Ahmida

Posted on February 25th, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Society & Politics in the Middle East.

One of the most interesting sites with updates and backgrounds on the revolts in the Arab world is Jadaliyya.com. Today they published their first interview conducted by Jadaliyya Co-Editor Noura Erakat with one of the leaders of the Libyan uprising: Ali Ahmida.

In this interview, Ali Ahmida (bio here) discusses how the recent civilian revolt began as a reformist movement and quickly transformed into a revolutionary one demanding regime change. Ahmida also places the opposition forces in their geo-political context in light of Libya’s legacy of post-colonial state building. Ahmida concludes by exploring the three possible scenarios in the next phase of Libya’s revolt. Please excuse the low quality audio at the outset of Ali Ahmida’s comments.

You can watch the interview HERE.

Jemen als 'Wild Card'

Posted on February 23rd, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Guest Author: Annemarie van Geel

Terwijl er de afgelopen dagen op het internet gediscussieerd werd hoe de naam Mubarak omgevormd kan worden naar een Arabisch werkwoord en wat dat woord dan zou moeten betekenen, gingen in Jemen mensen de straat op om te protesteren tegen het regime van Ali Abdallah Salih, de man die de afgelopen 33 jaar Jemen heeft geregeerd. In het Midden-Oosten, maar ook elders, word uitgebreid gegist over de vraag ‘wie is de volgende’. Op het eerste gezicht lijkt Jemen (in casu: president Ali Abdallah Salih) kandidaat te zijn.

Qat in Sana'a Foto Annemarie van Geel

Als armste land van de Arabische wereld -bijna de helft van de bevolking leeft van minder dan $2 per dag- heeft Jemen te kampen met een werkloosheid van ongeveer 35%. Corruptie, analfabetisme, een qat-verslaafde bevolking en een laatste plaats in het meest recente Global Gender Gap Report van het World Economic Forum maken het plaatje niet rooskleuriger.

Jemen is een complexe mix van stammen, religieuze groeperingen, en overige groepen. Salih heeft de ingewikkelde onderlinge verhoudingen tussen de verschillende groepen de afgelopen 33 jaar danig in zijn voordeel weten te manipuleren. Desondanks wordt het regime geconfronteerd met tribale rebellie van de Houthis in het noorden, een afscheidingsbeweging in het zuiden (dat tot 1990 onafhankelijk was), en Al Qaeda in het oosten van het land. Zelfs vóór het begin van de protesten stond Salih dus al aanzienlijk onder druk.

Die druk kwam onder andere van de oppositie-alliantie “Joint Meeting Parties” (JMP), bestaande uit islamisten, socialisten en wat kleinere oppositiegroepen. De JMP had al verschillende malen aangegeven op te zullen roepen tot protesten tegen Salih en diens partij de “General People’s Congress” (GPC) als er vóór de Parlementsverkiezingen van april van dit jaar geen politieke en electorale hervormingen zouden worden doorgevoerd.

Echter, de JMP is de “officiële” oppositie en tot op zekere hoogte gecoöpteerd door het regime. Maar naast de waarschuwing van de JMP werden er in Jemen, net als in Egypte en Tunesië, protesten georganiseerd door studenten via Facebookgroepen zoals “Eyoun Shabbah” (Ogen van de Jeugd) en “Harakat al Shabaab li Tagheer” (Jongerenbeweging voor Verandering). Deze groepen zijn een alternatief voor zij die gefrustreerd zijn geraakt met de officiële oppositie. In Jemen echter is internetgebruik vele malen lager dan in Egypte, en deze Facebookgroepen hebben dan ook slechts enkele honderden leden.

Een van de leidsters van de studentenprotesten is Tawakkul Karma. Toen Saleh op 23 januari deze activiste, die voorzitster is van Women Journalists Without Chains en lid van de islamistische Islah partij, liet arresteren leidde dit tot ongekende studentenprotesten in Sana’a, de hoofdstad, en Ta’izz (zuid-westen).

Tawakkul werd gearresteerd toen zij uit een vergadering kwam met de Secretaris-Generaal van de Islah partij (die deel uitmaakt van de JMP-oppositiegroep). Zij werd ervan beschuldigd demonstraties te organiseren en geweld en chaos te veroorzaken in de maatschappij. Vanwege de demonstraties tegen haar arrestatie kwam ze echter snel vrij. Salih verhoogde onmiddellijk de salarissen van soldaten met $25 per maand – een aanzienlijk bedrag in Jemen. In ieder geval voorlopig kan Salih nog rekenen op de steun van het leger.

Activiste Tawakkul Karman Foto Associated Press

Tawakkul ging na haar vrijlating direct weer de straat op. Tijdens een van de studentendemonstraties die ze leidde scandeerden pro-democratie studenten, refererende aan de voormalige president van Tunesië: “Ali, Ali, ga weg, ga weg, ga je vriend Ben Ali achterna” terwijl pro-regime studenten riepen “Ali of de dood, Ali of de dood” en “Jongeren, jongeren, Islah is de terrorist”. Ook de leus “de mensen willen de val van het regime” – die we ook tijdens de protesten in Egypte hoorden – wordt gescandeerd.

Op 2 februari gaf Salih aan zich niet te zullen kandideren voor de Presidentsverkiezingen van 2013 – een claim die hij ook maakte voor de Presidentsverkiezingen van 2006. Ook gaf hij aan de macht niet over te zullen dragen aan zijn zoon. Salih’s aankondiging kwam een dag voor Jemen’s Dag van Woede (5 februari) die werd geïnspireerd door de gebeurtenissen in Egypte en Tunesië. De avond van tevoren maakten pro-regime demonstraten kwartier op het centrale plein van Sana’a -net als in Cairo Midan Tahrir (Bevrijdingsplein) geheten- gewapend met posters van de president.

Bevrijdingsplein Sana'a Foto Annemarie van Geel

Ook de afgelopen week is er geprotesteerd in Jemen. En niet alleen op straat: de website van de Jemenitische staatstelevisie werd gehackt en even was er enkel te lezen: “Ga weg.. de bevolking wil je niet. 33 Jaar honger zijn genoeg! Een geweldloze revolutie.”

Deze week noemde Salih de pro-democratie demonstranten “anarchisten”, terwijl hij vrijwel tegelijkertijd opriep tot een Nationale Dialoog. Welhaast als antwoord vond er afgelopen vrijdag, 18 februari, een “Dag van Woede” plaats na het vrijdaggebed. Net als in Egypte werden mensen via Facebook en Twitter opgeroepen om te demonstreren. Veel mensen gaven gehoor aan de oproepen en er vonden demonstraties plaats in Sana’a (de hoofdstad), Ta’izz (de stad die het centrum van de pro-democratie demonstraties lijkt te zijn geworden) en Aden (waar de seperatisten de laatste jaren zeer actief zijn), alsook ook in Ibb, Abyan, Al Beidha, Hadramout, Dhalie en Hodeida.

Maar Salih lijkt geleerd te hebben van het lot van zijn collega’s Ben Ali en Mubarak en grijpt in. Veel mensen echter, vooral de verschillende stammen, hebben wapens, die gewoon in de souq (de markt) te koop zijn. De situatie zou dus wellicht grimmiger kunnen worden.

De demonstranten zijn niet alleen studenten maar ook islamisten, separatisten en leden van stammen. Deelname van die laatste twee groepen is niet vanzelfsprekend. Pas afgelopen woensdag sloten de separatisten, die jarenlang voor afscheiding waren, zich aan bij de protesten, wellicht denkende dat het vertrek van Salih ook al een aanzienlijke verbetering is. Zij roepen nu op tot de val van Salih en willen democratie. Een belangrijke verandering van tactiek, aangezien het de positie van de pro-democratie demonstranten aanzienlijk versterkt.

Oude stad van Sana'a Foto Annemarie van Geel

Ook de Houthis, de rebellerende stam in het noorden, hebben zich achter de demonstranten geschaard. Hoewel sommigen dit welhaast zien als een verkapte oorlogsverklaring hebben de Houthis (nog) geen strijders gemobiliseerd. Hussein al Ahmar, een leider van de Hashids (een van twee grootste stammen in Jemen) heeft aangegeven dat mocht de situatie in Sana’a uit de hand lopen zij zich achter de demonstranten zullen scharen. Zoals in Egypte en Tunesië het leger een centrale rol speelde in de protesten zouden in Jemen de stammen een bepalende factor kunnen zijn.

Tegelijkertijd riepen prominente geestelijken, zoals Abdelmajid al Zindani, op tot het vormen van een interim-eenheidsregering met leden van de oppositie op belangrijke ministeries en verkiezingen over 6 maanden. Tot deze oproep was Zindani één van de belangrijkste bondgenoten van Salih. Al Qaeda op het Arabisch Schiereiland houdt zich, afgezien van haar oproep tot jihad tegen de Houthis die shi’itisch zijn, afzijdig van de demonstraties.

De druk op Salih neemt dus toe en steun voor hem lijkt af te brokkelen. Later deze maand zou Saleh afreizen naar de Verenigde Staten, zijn belangrijkste bondgenoot. Maar gezien de recente ontwikkelingen in Jemen, en de toezegging van de oppositie om met hem te praten, heeft hij dat bezoek afgeblazen.

En de (nabije) toekomst? De oppositie is grotendeels verzwakt en/of gecoöpteerd door het regime. Onlangs accepteerde de JMP een initiatief van de regering voor politieke hervormingen, hiertoe aangemoedigd door de EU en de VS. De JMP echter heeft weinig geloofwaardigheid in het land. Gisteren verklaarde de alliantie niet meer bereid te zijn tot dialoog met het regime. Dat betekent niet dat de JMP niet wellicht straks tóch met Saleh aan tafel zit. Aan de andere kant lijkt de oppositie geen sterke leiders te kunnen leveren die ook nog de delicate balans tussen de stammen, religieuze groepen, en anderen zouden kunnen bewaren, hetgeen noodzakelijk is om het land politiek, economisch en sociaal bij elkaar te kunnen blijven houden.

De protesten houden vooralsnog aan. Jemen is een “wild card” en het is onduidelijk welke kant het op zal gaan in het land. Waarschijnlijk zal veel afhangen van hoe Salih de komende tijd omgaat met de protesten en de demonstranten en wat de uitkomst zal zijn van zijn eventuele gesprekken met de JMP.

Dus wat er gaat komen in Jemen – en in andere Arabische landen: “Allahu ‘alim”, ofwel, God mag het weten, zoals Arabieren soms zeggen.

Annemarie van Geel (1981) ontving haar Masterdiploma in Internationale Betrekkingen met het Midden-Oosten als specialisatie van de Universiteit van Cambridge in 2003. Ze heeft gewoond in Egypte, de Westelijke Jordaanoever, Syrië en Jemen en reisde uitgebreid door de regio. Ze heeft gewerkt bij Instituut Clingendael, het voormalig ISIM (International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World) en de Midden-Oosten afdeling van Amnesty International Nederland. Sinds 2011 begon is ze als promovendus verbonden aan de afdeling Islam en Arabisch van de Radboud Universiteit te Nijmegen waar ze onderzoek doet naar gender segregatie in Saoedi-Arabië en Koeweit. Annemarie van Geel heeft haar eigen website Faraasha.nl, waar dit stuk eerder is verschenen.

Jemen als ‘Wild Card’

Posted on February 23rd, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Guest authors, Society & Politics in the Middle East.

Guest Author: Annemarie van Geel

Terwijl er de afgelopen dagen op het internet gediscussieerd werd hoe de naam Mubarak omgevormd kan worden naar een Arabisch werkwoord en wat dat woord dan zou moeten betekenen, gingen in Jemen mensen de straat op om te protesteren tegen het regime van Ali Abdallah Salih, de man die de afgelopen 33 jaar Jemen heeft geregeerd. In het Midden-Oosten, maar ook elders, word uitgebreid gegist over de vraag ‘wie is de volgende’. Op het eerste gezicht lijkt Jemen (in casu: president Ali Abdallah Salih) kandidaat te zijn.

Qat in Sana'a Foto Annemarie van Geel

Als armste land van de Arabische wereld -bijna de helft van de bevolking leeft van minder dan $2 per dag- heeft Jemen te kampen met een werkloosheid van ongeveer 35%. Corruptie, analfabetisme, een qat-verslaafde bevolking en een laatste plaats in het meest recente Global Gender Gap Report van het World Economic Forum maken het plaatje niet rooskleuriger.

Jemen is een complexe mix van stammen, religieuze groeperingen, en overige groepen. Salih heeft de ingewikkelde onderlinge verhoudingen tussen de verschillende groepen de afgelopen 33 jaar danig in zijn voordeel weten te manipuleren. Desondanks wordt het regime geconfronteerd met tribale rebellie van de Houthis in het noorden, een afscheidingsbeweging in het zuiden (dat tot 1990 onafhankelijk was), en Al Qaeda in het oosten van het land. Zelfs vóór het begin van de protesten stond Salih dus al aanzienlijk onder druk.

Die druk kwam onder andere van de oppositie-alliantie “Joint Meeting Parties” (JMP), bestaande uit islamisten, socialisten en wat kleinere oppositiegroepen. De JMP had al verschillende malen aangegeven op te zullen roepen tot protesten tegen Salih en diens partij de “General People’s Congress” (GPC) als er vóór de Parlementsverkiezingen van april van dit jaar geen politieke en electorale hervormingen zouden worden doorgevoerd.

Echter, de JMP is de “officiële” oppositie en tot op zekere hoogte gecoöpteerd door het regime. Maar naast de waarschuwing van de JMP werden er in Jemen, net als in Egypte en Tunesië, protesten georganiseerd door studenten via Facebookgroepen zoals “Eyoun Shabbah” (Ogen van de Jeugd) en “Harakat al Shabaab li Tagheer” (Jongerenbeweging voor Verandering). Deze groepen zijn een alternatief voor zij die gefrustreerd zijn geraakt met de officiële oppositie. In Jemen echter is internetgebruik vele malen lager dan in Egypte, en deze Facebookgroepen hebben dan ook slechts enkele honderden leden.

Een van de leidsters van de studentenprotesten is Tawakkul Karma. Toen Saleh op 23 januari deze activiste, die voorzitster is van Women Journalists Without Chains en lid van de islamistische Islah partij, liet arresteren leidde dit tot ongekende studentenprotesten in Sana’a, de hoofdstad, en Ta’izz (zuid-westen).

Tawakkul werd gearresteerd toen zij uit een vergadering kwam met de Secretaris-Generaal van de Islah partij (die deel uitmaakt van de JMP-oppositiegroep). Zij werd ervan beschuldigd demonstraties te organiseren en geweld en chaos te veroorzaken in de maatschappij. Vanwege de demonstraties tegen haar arrestatie kwam ze echter snel vrij. Salih verhoogde onmiddellijk de salarissen van soldaten met $25 per maand – een aanzienlijk bedrag in Jemen. In ieder geval voorlopig kan Salih nog rekenen op de steun van het leger.

Activiste Tawakkul Karman Foto Associated Press

Tawakkul ging na haar vrijlating direct weer de straat op. Tijdens een van de studentendemonstraties die ze leidde scandeerden pro-democratie studenten, refererende aan de voormalige president van Tunesië: “Ali, Ali, ga weg, ga weg, ga je vriend Ben Ali achterna” terwijl pro-regime studenten riepen “Ali of de dood, Ali of de dood” en “Jongeren, jongeren, Islah is de terrorist”. Ook de leus “de mensen willen de val van het regime” – die we ook tijdens de protesten in Egypte hoorden – wordt gescandeerd.

Op 2 februari gaf Salih aan zich niet te zullen kandideren voor de Presidentsverkiezingen van 2013 – een claim die hij ook maakte voor de Presidentsverkiezingen van 2006. Ook gaf hij aan de macht niet over te zullen dragen aan zijn zoon. Salih’s aankondiging kwam een dag voor Jemen’s Dag van Woede (5 februari) die werd geïnspireerd door de gebeurtenissen in Egypte en Tunesië. De avond van tevoren maakten pro-regime demonstraten kwartier op het centrale plein van Sana’a -net als in Cairo Midan Tahrir (Bevrijdingsplein) geheten- gewapend met posters van de president.

Bevrijdingsplein Sana'a Foto Annemarie van Geel

Ook de afgelopen week is er geprotesteerd in Jemen. En niet alleen op straat: de website van de Jemenitische staatstelevisie werd gehackt en even was er enkel te lezen: “Ga weg.. de bevolking wil je niet. 33 Jaar honger zijn genoeg! Een geweldloze revolutie.”

Deze week noemde Salih de pro-democratie demonstranten “anarchisten”, terwijl hij vrijwel tegelijkertijd opriep tot een Nationale Dialoog. Welhaast als antwoord vond er afgelopen vrijdag, 18 februari, een “Dag van Woede” plaats na het vrijdaggebed. Net als in Egypte werden mensen via Facebook en Twitter opgeroepen om te demonstreren. Veel mensen gaven gehoor aan de oproepen en er vonden demonstraties plaats in Sana’a (de hoofdstad), Ta’izz (de stad die het centrum van de pro-democratie demonstraties lijkt te zijn geworden) en Aden (waar de seperatisten de laatste jaren zeer actief zijn), alsook ook in Ibb, Abyan, Al Beidha, Hadramout, Dhalie en Hodeida.

Maar Salih lijkt geleerd te hebben van het lot van zijn collega’s Ben Ali en Mubarak en grijpt in. Veel mensen echter, vooral de verschillende stammen, hebben wapens, die gewoon in de souq (de markt) te koop zijn. De situatie zou dus wellicht grimmiger kunnen worden.

De demonstranten zijn niet alleen studenten maar ook islamisten, separatisten en leden van stammen. Deelname van die laatste twee groepen is niet vanzelfsprekend. Pas afgelopen woensdag sloten de separatisten, die jarenlang voor afscheiding waren, zich aan bij de protesten, wellicht denkende dat het vertrek van Salih ook al een aanzienlijke verbetering is. Zij roepen nu op tot de val van Salih en willen democratie. Een belangrijke verandering van tactiek, aangezien het de positie van de pro-democratie demonstranten aanzienlijk versterkt.

Oude stad van Sana'a Foto Annemarie van Geel

Ook de Houthis, de rebellerende stam in het noorden, hebben zich achter de demonstranten geschaard. Hoewel sommigen dit welhaast zien als een verkapte oorlogsverklaring hebben de Houthis (nog) geen strijders gemobiliseerd. Hussein al Ahmar, een leider van de Hashids (een van twee grootste stammen in Jemen) heeft aangegeven dat mocht de situatie in Sana’a uit de hand lopen zij zich achter de demonstranten zullen scharen. Zoals in Egypte en Tunesië het leger een centrale rol speelde in de protesten zouden in Jemen de stammen een bepalende factor kunnen zijn.

Tegelijkertijd riepen prominente geestelijken, zoals Abdelmajid al Zindani, op tot het vormen van een interim-eenheidsregering met leden van de oppositie op belangrijke ministeries en verkiezingen over 6 maanden. Tot deze oproep was Zindani één van de belangrijkste bondgenoten van Salih. Al Qaeda op het Arabisch Schiereiland houdt zich, afgezien van haar oproep tot jihad tegen de Houthis die shi’itisch zijn, afzijdig van de demonstraties.

De druk op Salih neemt dus toe en steun voor hem lijkt af te brokkelen. Later deze maand zou Saleh afreizen naar de Verenigde Staten, zijn belangrijkste bondgenoot. Maar gezien de recente ontwikkelingen in Jemen, en de toezegging van de oppositie om met hem te praten, heeft hij dat bezoek afgeblazen.

En de (nabije) toekomst? De oppositie is grotendeels verzwakt en/of gecoöpteerd door het regime. Onlangs accepteerde de JMP een initiatief van de regering voor politieke hervormingen, hiertoe aangemoedigd door de EU en de VS. De JMP echter heeft weinig geloofwaardigheid in het land. Gisteren verklaarde de alliantie niet meer bereid te zijn tot dialoog met het regime. Dat betekent niet dat de JMP niet wellicht straks tóch met Saleh aan tafel zit. Aan de andere kant lijkt de oppositie geen sterke leiders te kunnen leveren die ook nog de delicate balans tussen de stammen, religieuze groepen, en anderen zouden kunnen bewaren, hetgeen noodzakelijk is om het land politiek, economisch en sociaal bij elkaar te kunnen blijven houden.

De protesten houden vooralsnog aan. Jemen is een “wild card” en het is onduidelijk welke kant het op zal gaan in het land. Waarschijnlijk zal veel afhangen van hoe Salih de komende tijd omgaat met de protesten en de demonstranten en wat de uitkomst zal zijn van zijn eventuele gesprekken met de JMP.

Dus wat er gaat komen in Jemen – en in andere Arabische landen: “Allahu ‘alim”, ofwel, God mag het weten, zoals Arabieren soms zeggen.

Annemarie van Geel (1981) ontving haar Masterdiploma in Internationale Betrekkingen met het Midden-Oosten als specialisatie van de Universiteit van Cambridge in 2003. Ze heeft gewoond in Egypte, de Westelijke Jordaanoever, Syrië en Jemen en reisde uitgebreid door de regio. Ze heeft gewerkt bij Instituut Clingendael, het voormalig ISIM (International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World) en de Midden-Oosten afdeling van Amnesty International Nederland. Sinds 2011 begon is ze als promovendus verbonden aan de afdeling Islam en Arabisch van de Radboud Universiteit te Nijmegen waar ze onderzoek doet naar gender segregatie in Saoedi-Arabië en Koeweit. Annemarie van Geel heeft haar eigen website Faraasha.nl, waar dit stuk eerder is verschenen.

Live Libya Uprising

Posted on February 22nd, 2011 by martijn.

Categories: Society & Politics in the Middle East.